Sanctions are hitting Russians where it hurts—in their grocery baskets

Russia’s already bad case of stagflation is getting worse. Earlier this week, the government slashed its economic forecasts, predicting that the country will soon slip into recession. A few days later, the latest inflation numbers added insult to injury, with prices rising by more than 9% in November.

Russia’s already bad case of stagflation is getting worse. Earlier this week, the government slashed its economic forecasts, predicting that the country will soon slip into recession. A few days later, the latest inflation numbers added insult to injury, with prices rising by more than 9% in November.

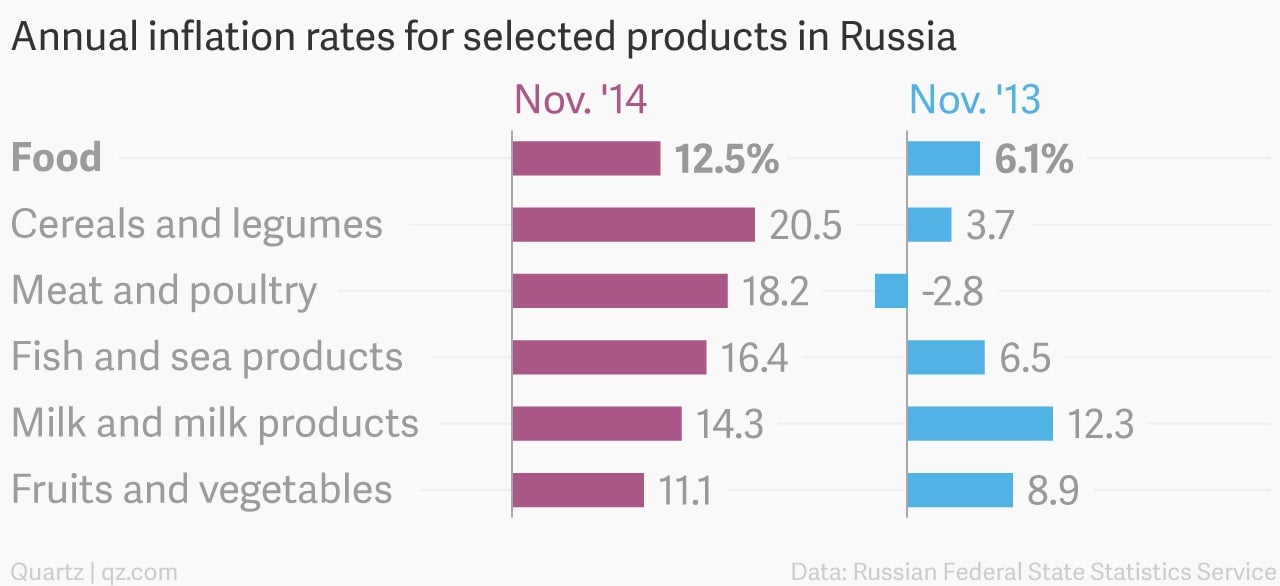

The tumbling ruble is to blame for much of the rise in prices, as it makes imported goods much more expensive. But another big factor is Russia’s counter-sanctions against food imports from the West. Food prices rose by more than 12% last month, according to the federal statistics service (link in Russian).

The embargo was pitched as retaliation for the financial and trade restrictions the West has imposed on Russia for its role in destabilizing Ukraine, which the Kremlin also spun as a boon for the local agriculture industry. But domestic producers have struggled to replace the meat, fish, dairy, fruits, and vegetables that Russia usually buys from abroad. This is clear in the prices for foods covered by the ban:

Among the specific products hit the hardest, fresh tomato prices rose by 35%, white cabbage by 24%, and potatoes by 21%. But the biggest rise of all was recorded in buckwheat, with average prices soaring by more than 50% in the year to November. Since Russia produces most of this staple itself, this is not down to sanctions, at least directly.

Rumors of a bad harvest for the popular comfort food seem to be behind a spate of panic buying, but others believe buckwheat acts a broader barometer of the public mood—in times of crisis, people stockpile the staple. So this too, in a way, reflects the impact of sanctions on the beleaguered Russian economy.

A survey last month found that 85% of Russians said that the food import ban did not pose any serious problems to them. But the risk is that the longer shoppers encounter barren shelves and higher prices at the market, the less enthusiastically they will support their government’s stand-off with the West.

The falling ruble already is causing tempers to fray among business leaders, with the head of Russia’s second-largest bank recently threatening to take critics “outside for a knuckle fight” in response to allegations that his bank was to blame. It will be a much bigger problem for the government if things get similarly testy in the supermarket aisles over the price and availability of goods on the shelves.