The hits keep coming for the Russian economy.

Oil prices are plunging after OPEC decided against cutting production last week. In response, today Russia’s economy ministry slashed its economic outlook, predicting a recession next year, along with inflation that will run just below 10%, and capital flight of more than $200 billion between this year and next. The Kremlin also just gave up on building a long-planned gas pipeline to southern Europe, as relations between Russia and the EU continue to deteriorate following the annexation of Crimea and the unrest in eastern Ukraine. Western sanctions imposed on Russia for its role in destabilizing Ukraine are pinching its economy, particularly its banks.

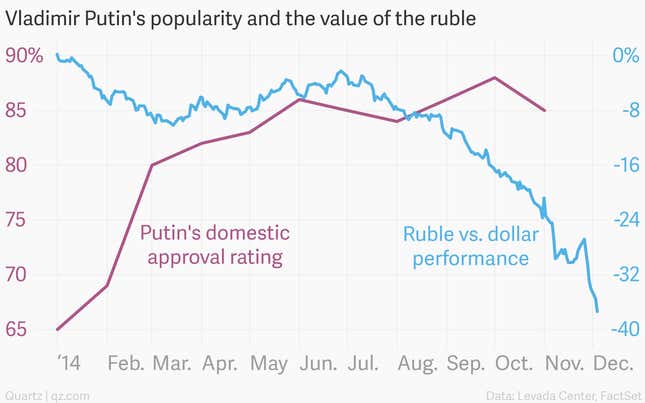

Yesterday, the ruble suffered its worst day against the dollar since the country defaulted in 1998. It’s falling again today, bringing the total decline to nearly 40% so far this year. If you consider the ruble a decent real-time gauge of the Russian economy, the signal is flashing red.

How will Russia react? You can cook up a bunch of ugly charts of the ruble, GDP, oil prices, inflation, and other indicators to support the suggestion that president Vladimir Putin may be forced to change course. But this graph is perhaps a better gauge of whether he will have a change of heart any time soon:

Despite the steady economic deterioration—as reflected by the tumbling ruble—Putin’s popularity at home has soared. Granted, the president’s approval rating slipped from 88% in October to 85% last month, but that will hardly ring alarm bells around the Kremlin.

Putin says he wants to stay in power for another 10 years, and the recent polls show the he will probably experience little resistance in doing so. A survey yesterday (link in Russian) suggested that he would win more than 80% of the vote if he faced re-election today.

We have written about the rationale for letting the ruble slide, most notably the effect that it has on boosting the local-currency proceeds of dollar-based oil sales. This lets the government stick to its spending plans, especially those that are popular with key groups of voters. But this can’t go on forever.

Although Russia’s economic ills have not yet filtered through into widespread popular dissatisfaction, even Russians’ famed adaptability and resilience—to stagflation, product shortages, and other hardships—have their limits. And if the tides eventually turn, the most telling signs will appear in the president’s sky-high, gravity-defying approval ratings. No other numbers seem to have much of an impact on Putin’s calculations.