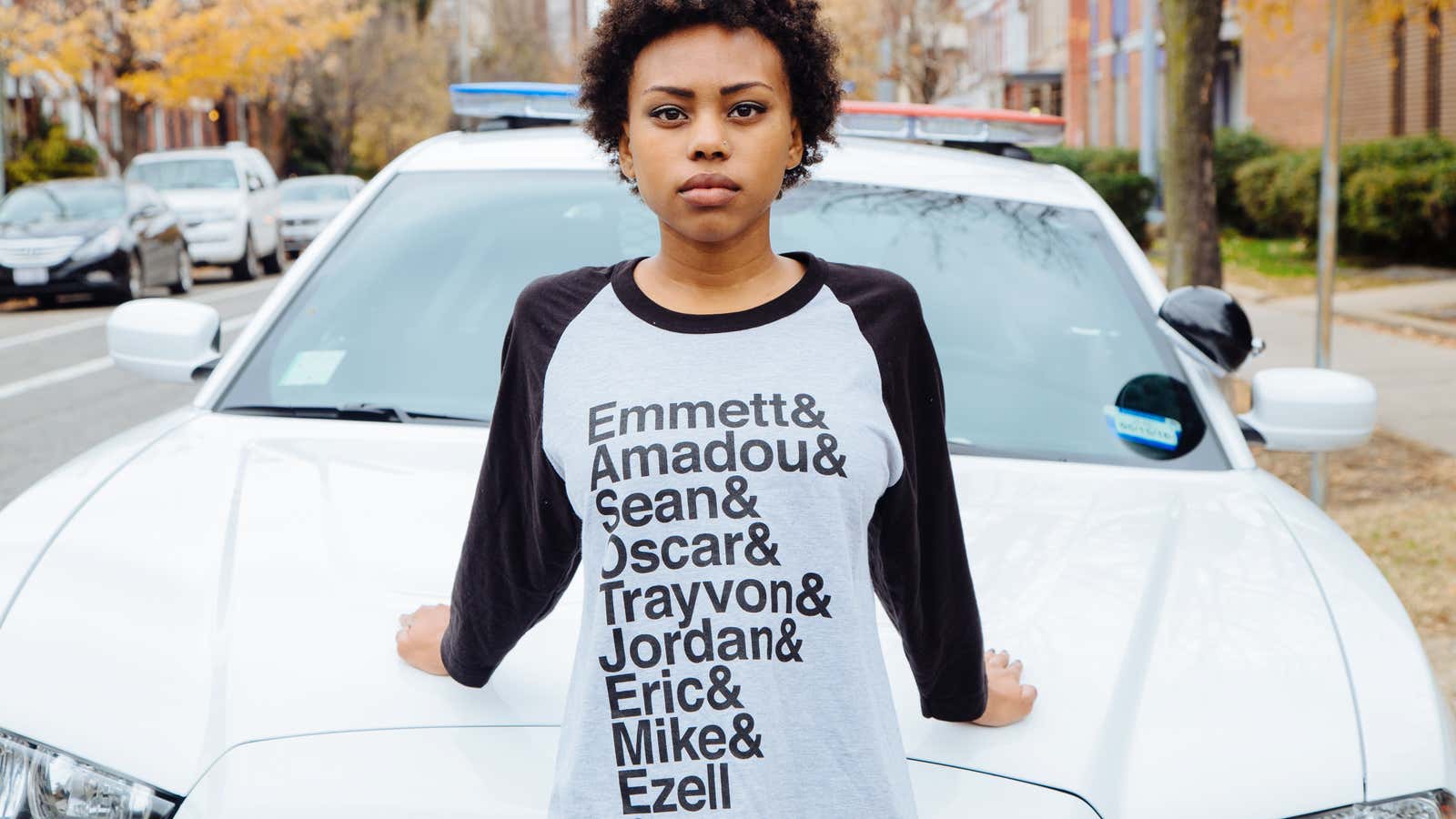

The design is incredibly simple: It’s just a list of names on a t-shirt.

Some of them—Trayvon (Martin), Eric (Garner), Mike (Brown)—are recent household names. Some—Emmett (Till), Amadou (Diallo)—first entered the public consciousness years ago. And still others—Oscar (Grant), Jordan (Davis), Ezell (Ford)—are more obscure. All of them, though, were black, unarmed, and killed under circumstances that made them symbols of racial injustice.

Amid recent debate over the US legal system’s handling of the deaths of Brown and Garner, both killed by police officers, sales of the shirts have surged. Some 500 orders came in last month, according to the shirts’ designer, 24-year-old Ryan Arrendell, who sells them as part of her small fashion label, GLOSSRAGS. Through the end of last week, that accounted for more than 40% of all the orders she’s received since she put the shirts up for sale in April.

“After someone dies, you definitely see a spike in sales,” she says.

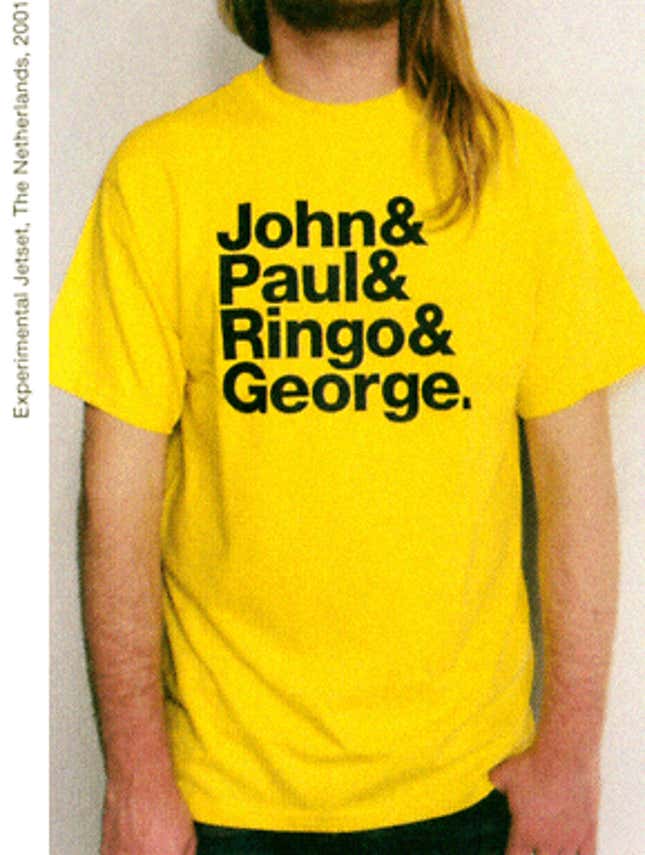

Arrendell’s shirts are a somber iteration of a widespread design meme. Stripped-down lists, usually in sleek Helvetica font, became fairly ubiquitous after 2001, when Amsterdam graphic design shop Experimental Jetset created what it called the “&&&-shirt” for Japanese brand 2K/Gingham. The shirt—with John&Paul&Ringo&George.—was a bare-bones Beatles homage.

“Our idea was to strip down the idea of a rock band to a list of four names, in an attempt to reach the essence of a group,” the company wrote in a piece explaining the aesthetic origins of the shirt.

The Beatles shirts went viral, and copycats began making similar lists for everything from basketball teams to video game characters—putting them not just on shirts but on pins, totebags, and the like.

Complex issues, explained simply

Arrendell got the idea for her t-shirt during last year’s 50th anniversary celebration of the March on Washington in the US capital. As she recounts on her website, she carried a sign echoing the &&&-shirt design during the event. Other people at the event repeatedly stopped her and asked to take pictures. After the march, she went home, sketched out a t-shirt shape on a Post-it note, scribbled the design down, and held onto it just in case.

A few months later, after consulting with a mentor about how to get the project started, she borrowed $500 from him to make an initial run of 100 shirts. They sold well when she debuted them at a local festival in her native Washington, D.C.

“It just made sense,” she tells Quartz. “The issues surrounding these men and women’s deaths are complex, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they need to be memorialized in an overly complex way.”

For months, the shirts sold modestly for $20 a piece—$25 after she upgraded her shirt vendors—on her website. She put most of the proceeds back into making more shirts. (She also put some of the money toward a donation to the Trayvon Martin Foundation.)

Arrendell says she understands if some would criticize her for profiting on tragedy. “I think it’s good that people are suspicious of things like this,” she says. “It’s good to have questions.”

Odd jobs

Arrendell graduated last year from Northwestern University, where she majored in journalism and African American studies. She moved home to Washington to help take care of an ailing grandfather, and has been supporting herself with odd jobs.

“I’ve been waiting tables, substitute teaching, working in retail, babysitting,” she says.

And updating her t-shirt design.

The first shirts Arrendell made had six names on them. This summer, she worked on a redesign, adding the names of Garner, the New York man who died in July after a police officer placed him in a chokehold, and Ford, who was shot and killed by police in Los Angeles in August. Two days after she sent the revisions to her printer, a police officer shot Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Soon she was getting requests to add Brown’s name to the shirts as well.

The new version of the shirt, which included Brown’s name, was available for sale by September. The shirts were quickly embraced as part of the the grief, outrage, and protest that followed Brown’s death.

DeRay Mckesson, an activist and prolific tweeter who has spent time protesting in Ferguson, says he was struck by the design’s directness when he first saw the shirt online.

“It humanizes the victims because it has names, but it also reminds you that these are not one-offs,” he says.

In October he began adding a link to Arrendell’s site in a newsletter he puts together. “Click here to purchase one of the now iconic shirts that lists of the names of the victims of black lives lost in state violence,” the latest edition reads, under the heading “Your Role in the Movement.”

There’s also a version of the shirt with the names of women. All of them—Eleanor (Bumpurs), Tarika (Wilson), Rekia (Boyd), Renisha (McBride), Yvette (Smith)—were unarmed when they were killed, except for Bumpurs, whom police officers shot in the hand and chest after she lunged at one of them with a knife.

Weighty responsibility

Arrendell isn’t sure what she wants to do with her clothing brand going forward. The one-time NPR intern says she wants to get back to journalism or pursue shirt designs with more levity.

But for now, Arrendell feels a duty to keep making the grim reminders.

And the names—they keep coming.

In October, a Michigan judge dropped an involuntary manslaughter charge against the officer who shot and killed 7-year-old Aiayana Stanley-Jones during a police raid being filmed for the A&E true-crime reality show The First 48.

In November, just days before a grand jury in Missouri decided not to indict police officer Darren Wilson’s for killing Brown, 28-year-old Akai Gurley of was killed by New York police in a Brooklyn housing project—officials called it “an unfortunate accident.“

Two days after that, a Cleveland police officer shot and killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice on an Ohio playground.

Arrendell says that for future versions of the shirt, she might have to use a smaller font, or print names on both the back and front to make them all fit.

“There’s only so much more space you can have before names get lost,” she says.