You know the story: An emerging market brimming with potential really starts hitting it, generating growth and prosperity, but as it moves into the middle of the global economic table, things slow down. Hopes for future wealth diminish. It’s trapped.

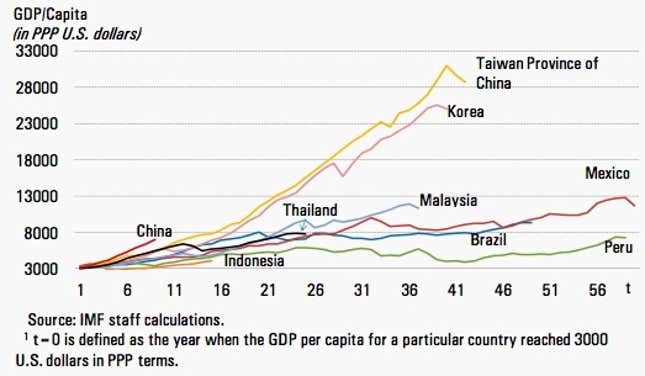

For examples of this trend, you might look to Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, or Thailand, countries that saw per capita income stagnate after achieving middle-income status. There are counter-examples, though: consider South Korea and Taiwan, which went from the range of 10% to 20% of US income up to the 60%-70% range with nary a pause.

The latest fear is that China will look less like South Korea and Taiwan and fall into the same trap as other emerging markets—with potentially significant implications for the global economy. But now, economists Lawrence Summers and Lant Pritchett say that this isn’t the right way to think about development economics—and that fears of the middle-income trap may make it a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In new research, they’ve tried to identify predictors of a growth slowdown—and income levels are a poor one, according to their study.

Instead, they see fast growth as a more reliable warning of a future slowdown. They suggest reversion to the mean as an explanation: Just like a star athlete may underperform in his second year in the league—a sophomore slump—so might a country, after outperforming expectations for a period of time, have bad season, too. The ups and downs don’t necessarily mean that the player or country is any better or worse than before, it’s just variance in performance or sheer luck (for countries, that’s often in the form of a fossil fuel find).

The distinction is important because it can guide policymakers’ reactions to a slowdown, the problem Chinese leaders are wrestling with today. Summers and Pritchett fear that ”acting to sustain an unsustainably high growth rate may lead subsequent adjustment to be much harsher.”

They also fear that mislabeling a slowdown as evidence of the middle-income trap leads policymakers to solve the wrong problem, perhaps prompting them to try building an information economy before needed industrial or agricultural infrastructure is in place, or, on the other side of the coin, digging in to protect established industries and cronies to the detriment of new businesses and sectors.

So perhaps policymakers should think of themselves less as a big-spending team set on finding the next breakout star, and instead play—forgive me—moneyball, building a foundation for the many seasons ahead.