Taking video of people harassing your family can get you busted in the EU for privacy violations

If you’re a resident of the European Union and you’re planning to add a few smart home cameras to your cozy nest, or perhaps buy a video-ready drone, you might want to hold off. The Court of Justice for the European Union (CJEU) sent down a ruling this past week regarding filming public spaces with private home monitoring cameras for which legal experts say may impact a much wider set of technologies in the emerging Internet of Things (IoT).

If you’re a resident of the European Union and you’re planning to add a few smart home cameras to your cozy nest, or perhaps buy a video-ready drone, you might want to hold off. The Court of Justice for the European Union (CJEU) sent down a ruling this past week regarding filming public spaces with private home monitoring cameras for which legal experts say may impact a much wider set of technologies in the emerging Internet of Things (IoT).

The ruling, which came in the case of a Czech man who used CCTV on his house to film people harassing his family, could rock the boat for IoT manufacturers and aficionados alike in the EU. In particular, the ruling has potentially far-reaching implications for people who use devices in their private homes to capture public activity, film or take photos from private drones in public places, take smartphone footage in public, or otherwise capture other people’s data on personal devices which could be used to identify a person without their consent.

Forget you

Europe passed strict data privacy laws in the late 1990s that protect the individual’s rights around their own personal data. These regulations have been updated several times since in attempts to adapt to the changing technology landscape. Another round of updates are currently being debated (some would say diluted). Broadly, these rules prohibit capture of personal data without an individual’s consent, and set out strict guidelines about how such data can be stored and moved around. There are narrow “personal use” exemptions that apply inside a private home, which this week’s ruling made even narrower.

Eurocrats have played catch-up to keep up with the boom of global social networks, cloud computing, and, lately, new forms of connected devices, sensors and other so-called “smart’ objects that make up the IoT. These tensions have most recently surfaced in the EU’s battle with Google and other tech giants over the so-called “right to be forgotten,” which allows individuals to apply for their private information to be removed from search engines.

In the case just decided, František Ryneš, a Czech citizen, used a personal CCTV camera installed in his home—but pointed at the street—to catch images of his assailants after his family and home had previously been attacked. While he did capture those images, and the attackers were prosecuted, the court ruled his camera also caught images of people on the street where the camera was pointed, as well as a neighbor’s house, and saw both violations of the personal use exceptions to data protection. The fact that Ryneš’s camera was connected to a hard drive, as many consumer surveillance cameras can be today, and that images of passers-by were potentially stored there, prompted the CJEU to rule as it did.

Drones and phones and smart homes, oh my

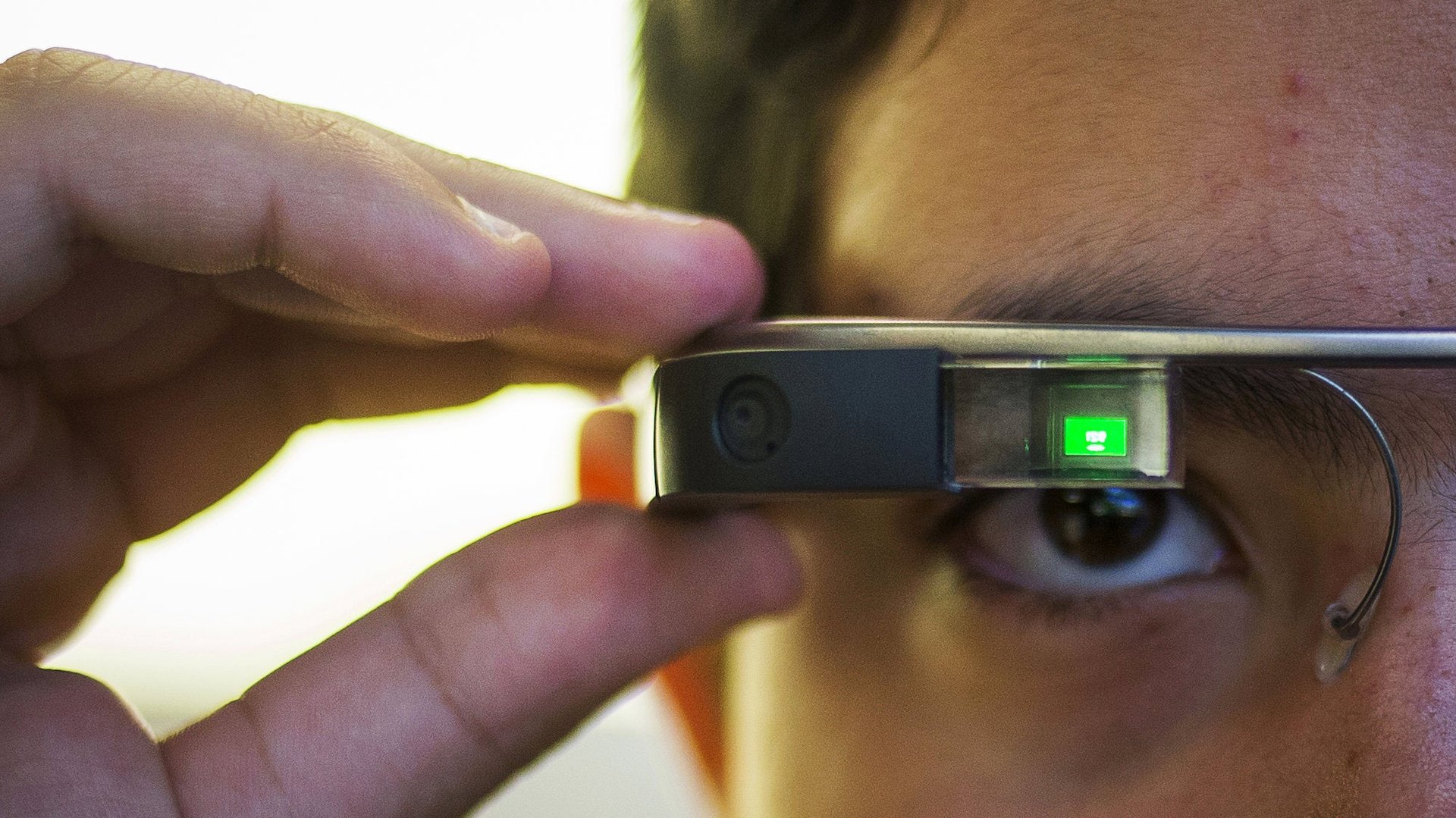

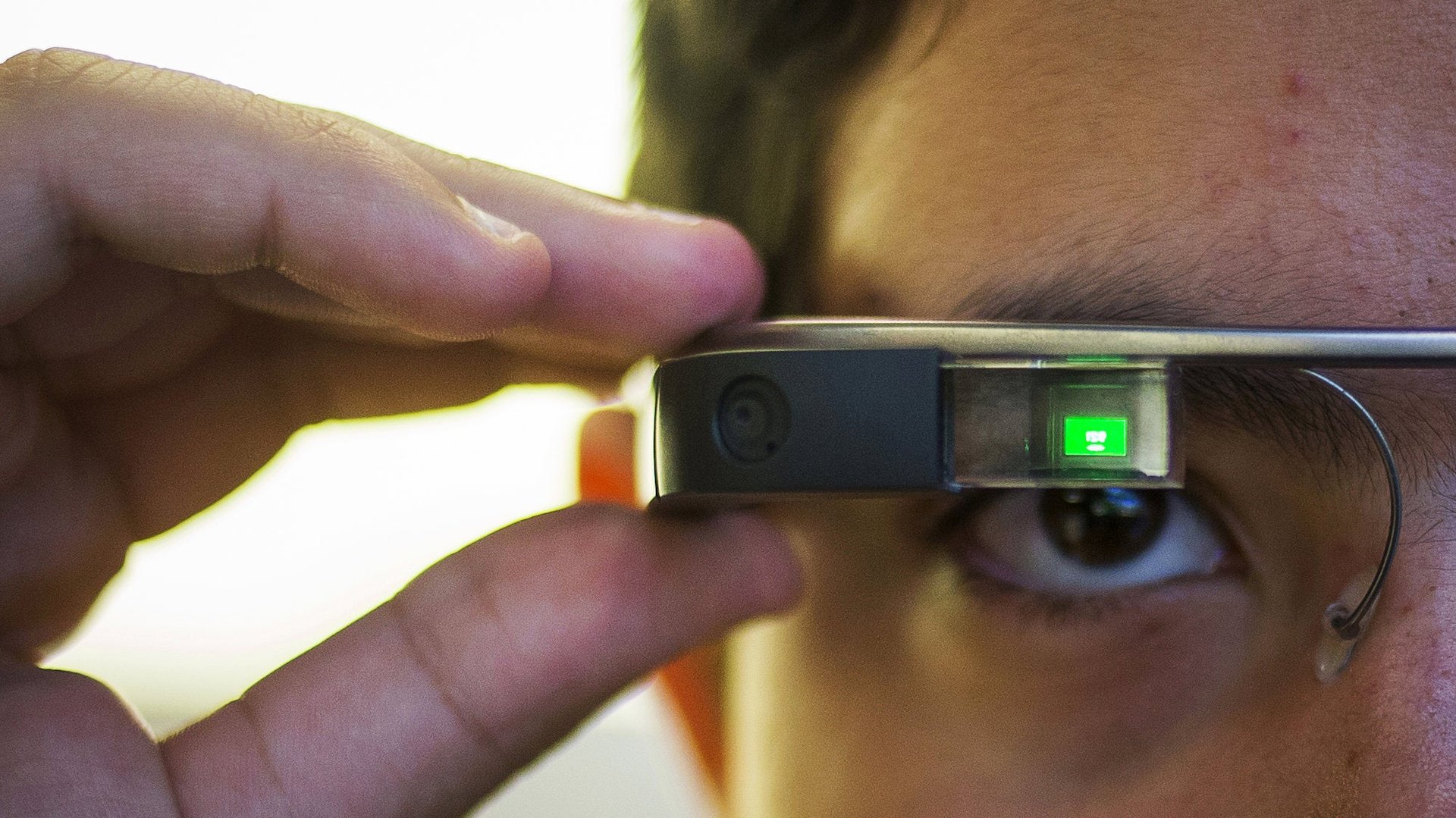

This may seem like a narrow issue, but legal experts immediately responded that the court’s approach may also cover other personal gadgets, both mundane and controversial. “In addition to CCTV, drones and body worn video used by local authorities and the police in the law enforcement context,” wrote University of Essex law professor Lorna Woods just after the ruling, “we should think here about mobile phones with cameras and devices such as Google glass [sic], which have already been flagged up as potentially problematic in regulatory terms.”

The EU is already worried about the potential privacy quagmire that IoT represents, where everything from networked cars to connected air conditioners to smart thermostats can collect and share data about individuals with a myriad of third parties in milliseconds. Even smartphone video of a child’s Christmas play uploaded to Facebook could now be problematic within the region, as one legal pundit pointed out. But, in a working paper released in August (pdf), it was noted that as current data protection rules evolve, bureaucracy struggles to keep up with the pace of change, to say nothing of individual consumers themselves.

Data sieves and data thieves

Given the nearly infinite ways data can now be grabbed and sent to manufacturers, app developers, advertisers, credit bureaus and governments from the devices we wear, fly, stick on a bookshelf, or sneak into the bedroom, protecting personal data becomes difficult not just for the technologies’ creators, but doubly so for legislators. The issue is increasingly not just what data is captured, like a heart rate, utility use or books read, but what kind of inferences can be gleaned from that data, and by whom. These days data collected from personal technology can report on anything from finances and health, to sexual orientation or political beliefs. In short, new forms of data profiling mean new kinds of exposure.

The current trend seems to feature major tech companies playing rope-a-dope with Europe’s legislators and judges, who are almost forced to write and interpret law in ways that are sadly hamfisted, which most would agree was the result in the Ryneš case. Even so, fly-by-night app makers and malware foundries continue to carry on with business as usual, grabbing and selling personal data where they can find it, and disruptors keep disrupting, throwing dozens of new connected, data-hungry products and services into the market weekly.

Existing and new classes of technologies may suffer in the near term as regulators make best efforts to tune the law. Some of Europe’s politicians and homegrown technology companies fret that American competitors, thriving under far more lax privacy laws, have an advantage. However, if this ruling is an indicator, the days of vacuuming up and storing personal data in all but the most strictly defined ways may be coming to a close, at least in the EU.