Just a week after US president Barack Obama and Cuban president Raúl Castro made history by announcing that the United States and Cuba would normalize diplomatic relations, much focus in the American media has been on the isolation that Cuba has lived in for over five decades.

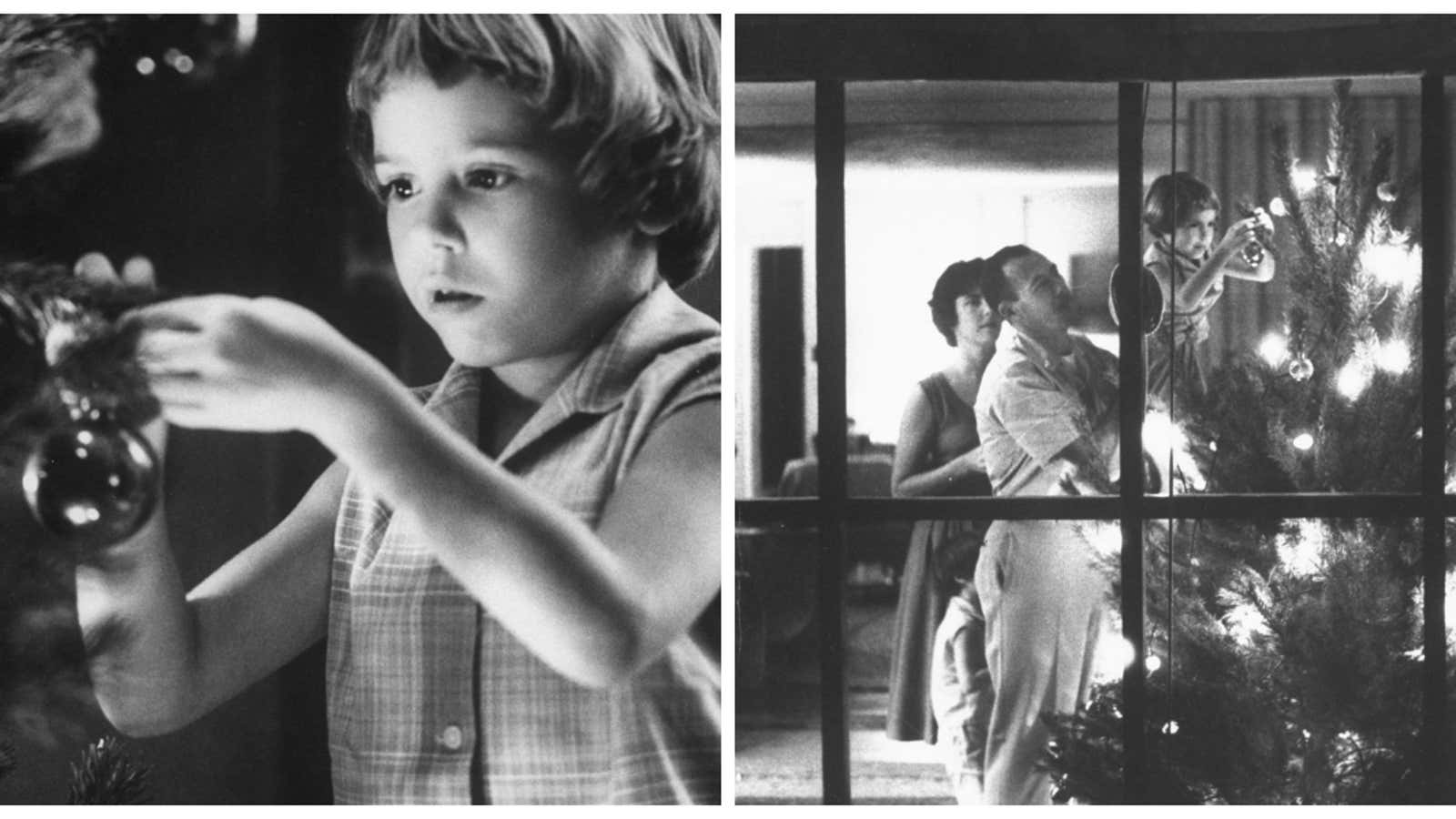

Part of that isolation extended to Christmas. From 1969 to 1998, ending with Pope John Paul II’s visit to the island, Christmas was officially banned by the government in a period known in Cuba as Las navidades silenciadas or “The Silent Christmases.”

Rebtel, a Swedish low-cost mobile carrier, this month released an internet campaign, “The Lost Christmas,” as part of its promotional launch of a new service offering international calls to Cuban mobile and landline phones. A company representative in Miami called and interviewed five Cubans, whose surnames are not revealed, who had grown up in this era. Many were children when Christmas on the island suddenly went underground.

“I remember my Uncle Antonio gave us a plastic old broken Christmas tree which we kept hidden,” says Angela, 59, of Havana. “I don’t know how he got it. We enjoyed the tree anyway, even if we couldn’t light it at night.”

Abel, 45, also of Havana, recalled: “My generation, those of us who grew up in the 60s, lived with the myth of Christmas created for us in the stories that our grandparents shared with us.”

The reasons that Fidel Castro’s government officially terminated Christmas were both economic and political. In October 1969, in an effort to fuel economic growth at a time of financial crisis, the government announced an ambitious plan to boost the country’s sugar cane industry. The Zafra de los diez millones or “The ten million harvest” was a national effort to export 10 million tons of sugar cane abroad. To avoid interrupting the harvest, Christmas and New Year’s celebrations were moved to July and Dec. 25 became a normal working day.

Also during that period, the government was seeking to institutionalize its secular revolution and saw religion and religious holidays as a counter force to that national project, said Enrique Sacerio Garí, a professor of Hispanic-American studies at Bryn Mawr College and an expert on Cuba.

Garí, 69, was born and raised in Cuba and has made dozens of trips back since he moved to the US in 1959. He said he understood the sentiments expressed by those interviewed in Rebtel’s promotional campaign, but also said they fail to tell the full story.

For one thing, he says, Christmas really came out from the shadows in 1991, when Communist party members were given permission to practice religion openly. And, he explains, many Cubans maintained Christmas customs even during the “Lost Christmas” period, such as the traditional Christmas Eve dinner where lechón asado or roasted suckling pig is served.

In fact, Garí tells Quartz, in some ways Cuba’s Christmas celebrations have maintained the holiday’s sincerity in ways that it has been lost elsewhere. ”Cuba differs from others in that, in this 30-year period, Christmas was marketed around the world as a business, and the religious aspect of it largely went away,” he says. “Cuba wasn’t part of that commercialization of the holiday, so to speak.”

Since Christmas returned as an officially recognized public holiday in 1998, Garí says, Cuba’s “Lost Christmas” generation views the day as a cultural spectacle, rather than a religious ritual. Cubans buy trees and decorate them with ornaments, and sometimes even exchange gifts.