Last year, we almost gave up on Santa Claus. On Christmas Eve, we were in Bangkok, having just spent five days in Cambodia. We had clambered up Angkor Wat, listened to lilting music played by the victims of land mines, watched a circus entirely staffed by former street children. My husband and I talked to our children about what they had seen. This Christmas, perhaps, they could ask Santa to give their presents to some of the children in Cambodia.

Bangkok, though, was brightly decorated for Christmas. There were Christmas carols, holiday wreaths, Christmas trees everywhere, with presents underneath. Inevitably, our children, being young, wondered, “What’s Santa going to bring us for Christmas?” They didn’t want anything big, they said. But surely, Santa would bring them something small enough to be tucked into the suitcases for the long flight home.

Caught up in planning and packing for our trip, we had not had the foresight to pack Christmas gifts for our kids. Now, thousands of miles away from home, we were in a strange city with little energy to shop for presents or room to hide them. Was it time to finally bid farewell to Santa Claus, I wondered?

Every year around this time, parents discuss how and whether to keep Santa alive. I had worked hard to keep Santa Claus real for our children and not because I wanted to keep a childhood tradition alive. Growing up in India, Christmas was about visiting friends for the richly spiced aroma of homemade plum cake, twinkling lights on small Christmas trees and Christmas carols. It wasn’t about leaving cookies for Santa or waking up to presents.

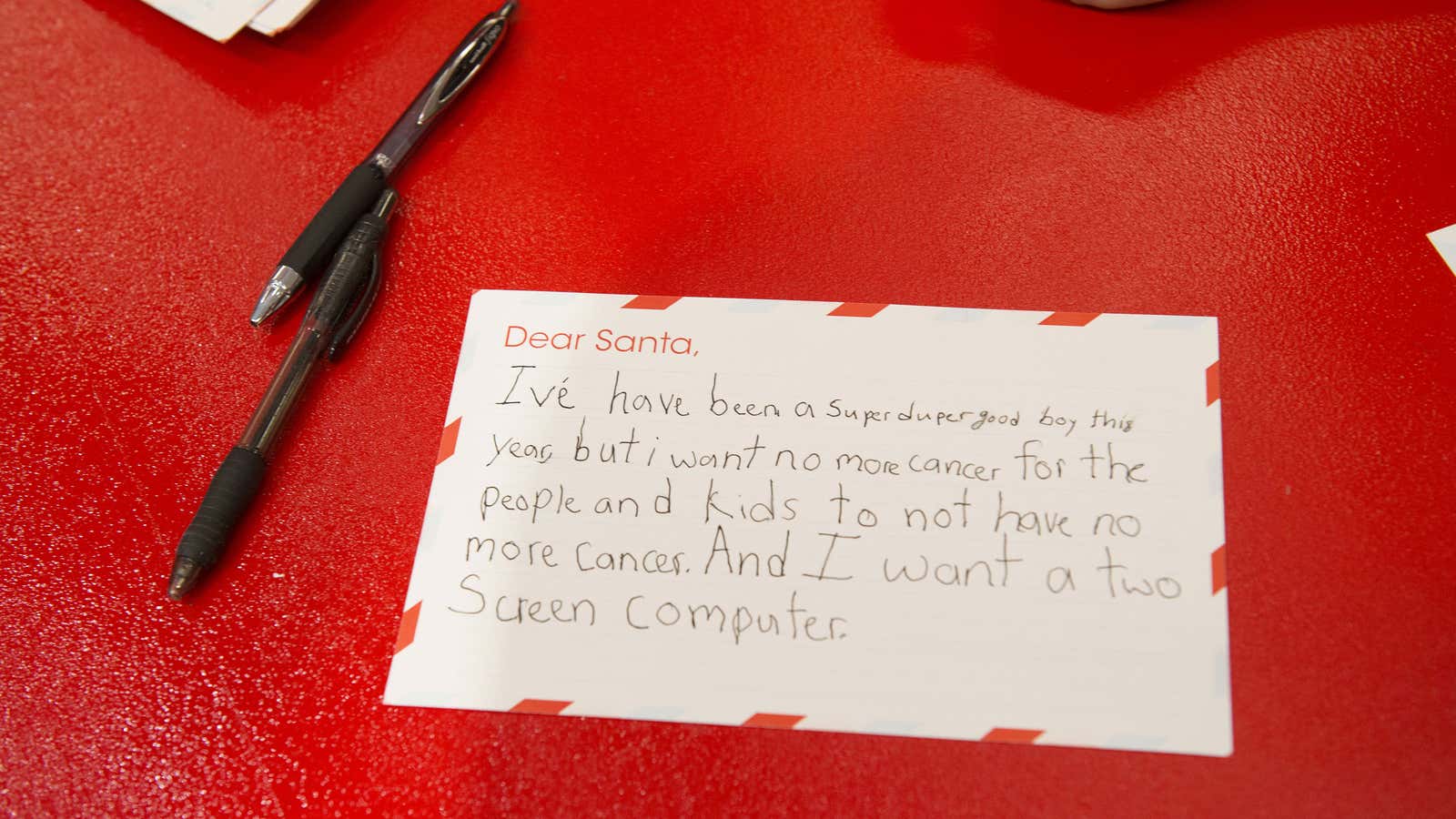

I want Santa to be real for my children because I see their letters to him as a magic window into the most important things in their lives, their interests and their emotional wellbeing. There is something lovely about writing to Santa. These are letters that are written without fear of being judged, just simple, straightforward glimpses into a child’s heart. It is a secret between a child and Santa, the one person that they believe is real and has magical powers. For geek parents like us, Santa’s gift is unfiltered data about who our kids are and how they see themselves and the world.

My children have small wish-lists for Santa. They usually want just a book, or a toy. The brevity of the lists makes me happy: I want them to be content with what they have, not hanker for more.

Two years ago, the only thing that our daughter wanted was the story of the Pied Piper. We were in Chennai, in south India. It took my husband visits to two bookstores before locating a copy, to be hidden away in a drawer and discovered the next morning.

When the kids were four, Santa missed our house entirely. We were in New Delhi and had inexplicably forgotten presents. Luckily, our children had sat through the city’s horrendous traffic jams. Santa, we explained, was unable to find us because of the city’s terrible traffic. Their gifts would be waiting at home in Chicago. Sure enough, there were presents waiting from Santa in Chicago, and were met with rapturous cries.

Back in Bangkok, we were tempted to sit our kids down and burst the Santa mystique. They were seven and surely old enough to understand. Still, we couldn’t bring ourselves to close that magical childhood window. As my husband distracted the kids, I bought two make your own Thai paper puppets that could easily be slid under their pillows.

The puppets were a flop, but the ploy worked and Santa stayed real. This year, our daughter has only one thing on her list. “Dear Santa,” she wrote. “I want no presents this year. Please give my gifts to poor children. I hope you have fun riding from place to place.” Our son has two things on his list for Santa: anything Star Wars related and a baby brother. Santa, he thinks, will understand just what it is like growing up with a sister and lots of girl cousins but few boys.

Our magical data gathering window is still open.