A few weeks ago, I arranged an ice breaker at a kick-off fundraising event for the feminist giving circle I helped found in New York with five other women in their late 20s. Everything about the night pointed to the new, millennial feminism my generation is ushering in—but this was most clear via the game itself, which involved guessing the name of the iconic woman taped to your back by asking yes or no questions—and which featured Audre Lorde and Aung San Suu Kyi next to Taylor Swift and Beyoncé. Dozens of people of all stripes showed up, not deterred (as some of us expected) by the word “feminist” in our title, and they easily guessed the names of all the women—pop and political.

When the event ended, I rushed downtown for a completely different experience—I joined the 500 million other viewers watching the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show because I was certain it would ooze with the kind of contrived, over-the-top branded feminism I wanted to report on for my weekly online newsletter. Leading up to the show, all the elements were there—the company’s heavy use of the word empowered to describe the “angels” (they work hard for their sexy bodies and paychecks), the recent feminist comings out of former angel Tyra Banks and current angel Elsa Hosk, and the fact that journalists covering the show weren’t allowed to use the F word. If 2014 was the year of celebrity feminism and anxiety over cooption of the movement, this end of the year show should have been the grand finale: the diamond encrusted women’s symbol on a $2 million Fantasy bra, the giant faux feminist rally we’d been expecting.

But nothing happened. I came up dry after sifting through millions of tweets for feminist-lite hashtags, and it was then that I realized that 2014’s branded feminism is OK, because feminism itself can never be for sale.

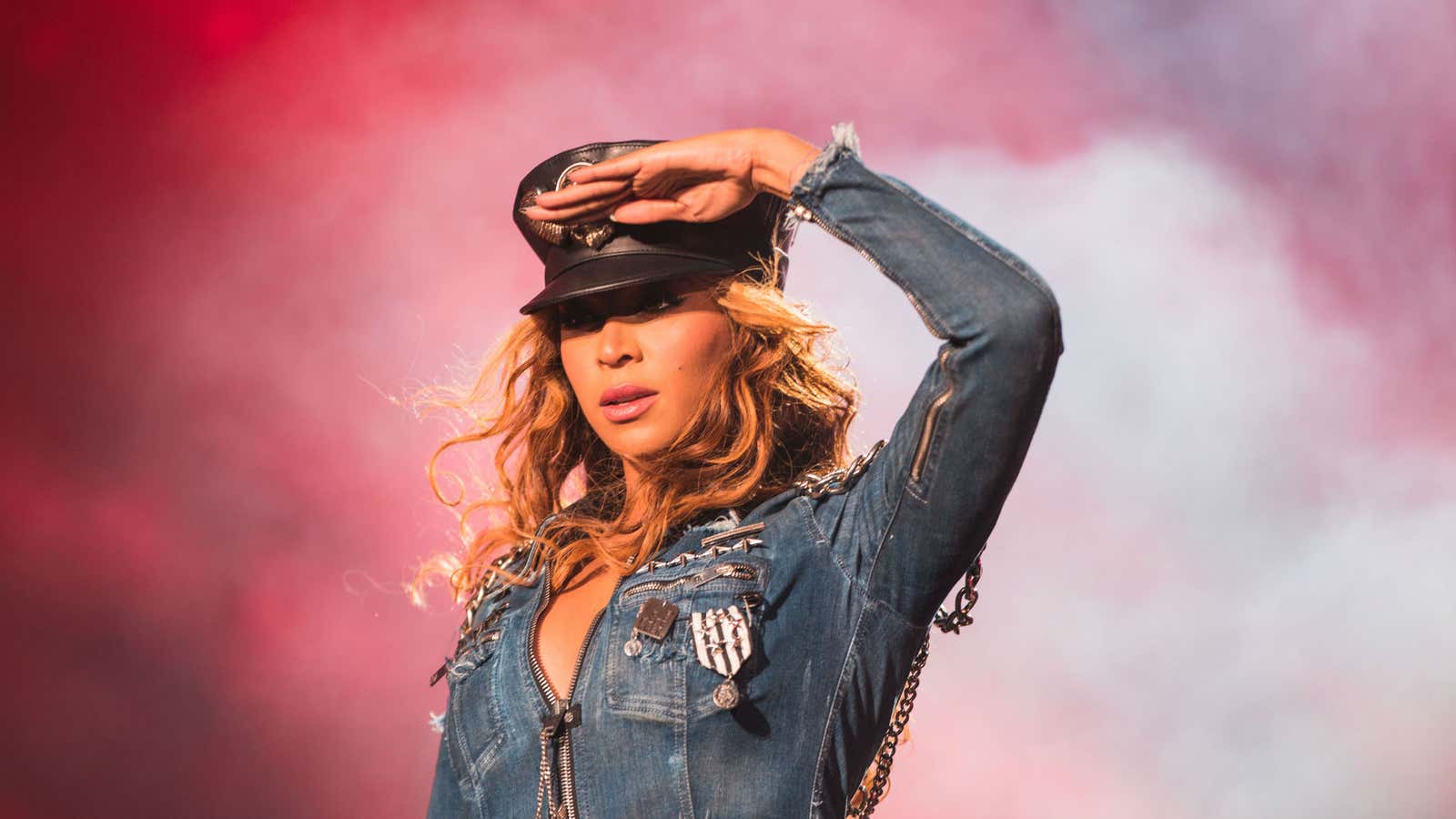

Feminism is literally trending this year—information about the term was searched five times more in 2014 than in 2013. This is the year advertisements didn’t just sell girl-power flavored products, they morphed into fempowerment campaigns or femvertisements and attempted to package feminism itself, as if to say, “This feminist moment is brought to you by Verizon (or Always, GoldieBlox or Dove).” This is the year of celebrity feminism—it’s when Beyoncé stood in front of a blazing FEMINIST sign at the MTV Video Music awards, Taylor Swift realized, with the help of Lena Dunham, that she’d been a feminist all along, and a handful of male celebrities embraced the term, too. This year, there’s been an undeniable shift in the conversation about what makes a “good” or “bad” feminist, and its arguably the most visible the movement has ever been.

But with increased visibility comes pushback, and I don’t just mean from antifeminist trolls and mansplainers. There’s a growing anxiety among some feminist gatekeepers about mainstreaming feminism into pop culture and the staying power of branded feminism. If the movement’s next generation is defined by hashtags and lists of ranked feminists and shampoo commercials, how will the real work ever get done? If celebrities take over, don’t we run the risk of hero-worship, which undermines the collective spirit of the movement? If branded feminism is what’s being offered to millennials, how will they choose to engage with it? The real anxiety seems to be: will millennials ruin feminism?

I get it, but no, we won’t ruin feminism.

I admit that while living and working with women’s human rights groups on the Thai-Burma border last year, I often rolled my eyes across continents at what I thought was a budding slacktivist-filled, Internet feminism back home in the US—could this hashtag generation be trusted to fight for women’s human rights in solidarity with my badass Burmese co-workers who did the real work on the ground? Millennials, after all, are supposed to be lazy, entitled, narcissistic selfie-takers. But as 2014 ends, I’m no longer worried about my generation’s feminism, as branded as it seems, because it represents a larger cultural moment and generational shift that might actually be working.

Millennials are internet natives, and that’s not a bad thing. We understand that we are all personal brands, signaling political views and allegiances with every Facebook “like” and re-tweet. Personal narratives become hyper-visible on social media, and while claiming an identity may not translate to action immediately, it brings larger issues to the forefront, calling forward previously invisible dialogues. We can worship Beyoncé while questioning her feminism because we’re skeptical of brands—each celebrity feminist coming out was met with applause and the questions, “But how do they do feminism? Do they include race and class in the analysis?” and we know that celebrity feminism can’t define the entire movement, but it’s a critical point of departure.

Millennials are open to change. We get that Taylor Swift’s feminist journey has been winding and imperfect, just like the movement itself, and just like the rest of us bad feminists. We are the most educated generation in history, driven by a knowledge-based economy, but are wary of higher education—watching bell hooks talk to Laverne Cox and Janet Mock online makes these conversations accessible outside the ivory tower. We’re obsessed with transparency and authenticity and we interact with brands differently than other generations, so we applaud innovative ads but see through contrived marketing schemes. When Elle magazine promoted feminist t-shirts and Benedict Cumberbatch wore one, we clicked “like” while simultaneously researching his feminist credentials, and the labor practices involved in making those t-shirts. Feminism has never been an easy sell, but no ad campaign or celebrity is powerful enough to commodify an entire movement.

I’m not worried about millennial feminism because we’re a surprisingly altruistic generation longing to be part of something bigger than ourselves. During the hour I spent searching for faux feminism in the Victoria’s Secret Fashion show, my phone buzzed with texts from the giving circle—we raised enough money that night to fund a feminist-led human rights group, a foundation offered a matching gift, and strangers wanted to know how they could donate their time and money.

I don’t have all the answers or know if 2015 will bring significant social change. But I do know that when Beyoncé used Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s words to define her feminism, Twitter exploded with feminist hashtags and celebrities helped each other “come out,” I felt pretty good about this new wave that (critically) accepts new brands of feminism, but will never allow it to be sold.