Despite controlling some 70% of production, China has quietly conceded its inability to control the market for rare earth elements, which are used in a variety of high-tech devices and manufacturing processes.

China’s announcement that it will end export quotas on the elements comes after an August WTO finding that the limits violated global trade rules. But the real nail in the coffin was the power of the market: China didn’t appeal the decision because the quotas did little to affect the market for the metals.

It didn’t seem that way during the great rare earth element panic of 2010, when prices rose along with geopolitical tensions between China and Japan. After an incident in the South China sea, China used an embargo on rare earth exports—alleged by Tokyo denied by Beijing—to push back against Japan, a major consumer of the materials. After Japan backed down, the US and other nations worked themselves into a bit of a tizzy over the possibility that China could block their access to important industrial resources.

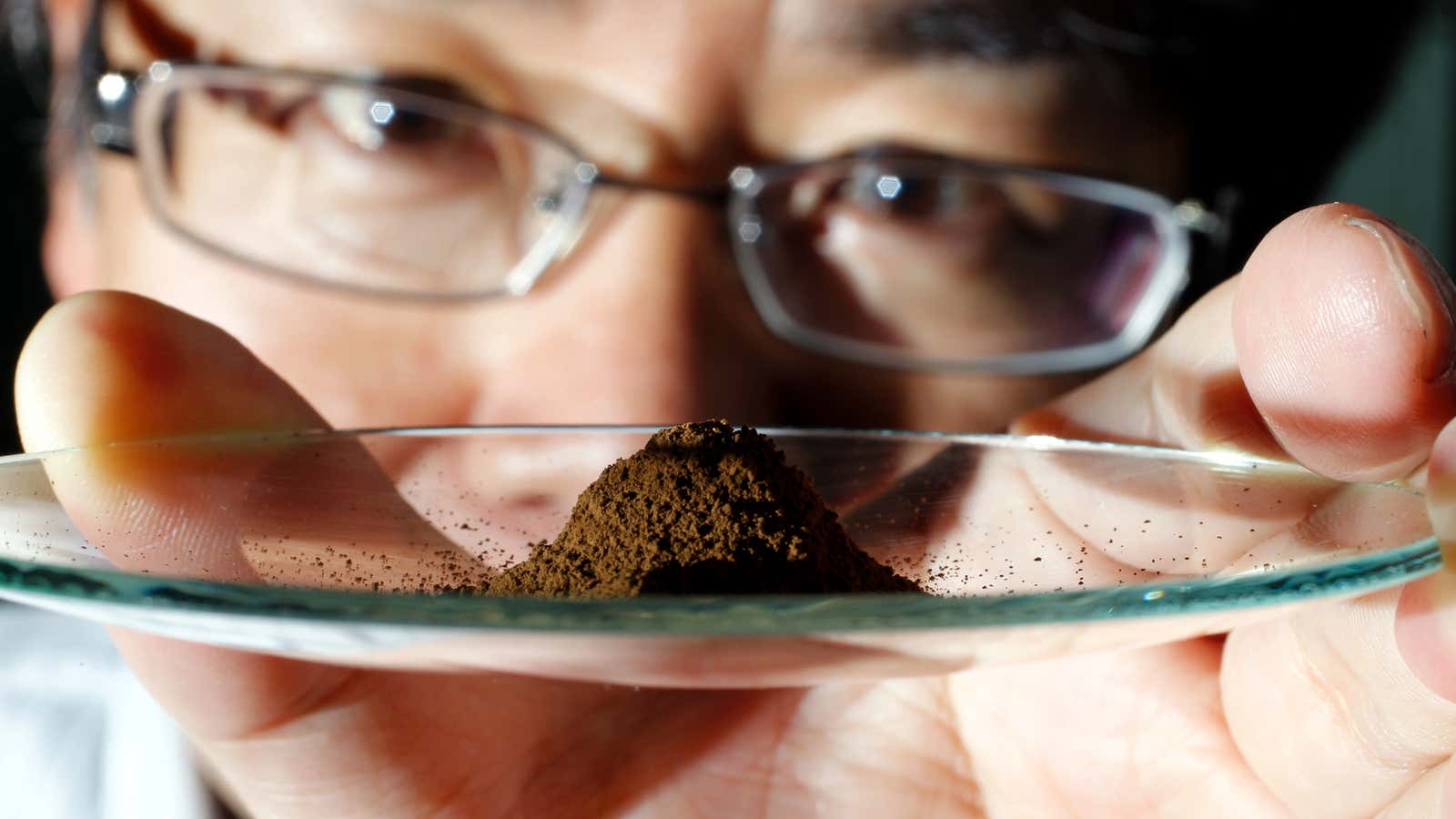

But, if you know anything about rare earth elements, they aren’t rare, just a messy hassle to produce. China became the world’s leading supplier of these elements in part because of laxer environmental rules around refining them from ore. And when it seemed like Beijing was ready to use its near-monopoly to enforce its political preferences, OPEC-style, two things happened, as tracked by University of Texas professor Eugene Gholz:

1. There was a price bubble.

Suppliers of rare earth elements, and manufacturers who used them, began stockpiling the minerals, fearing China’s future capriciousness.

2. The price bubble went away.

That’s the thing about high prices: They inspire creativity. First, a number of rare earth element end-users came up with ways to substitute for or otherwise avoid using the increasingly expensive commodities. Second, a number of mining companies—in the US, Europe and Australia—saw an opportunity to invest in expansion of their facilities, and begin producing more of the increasingly expensive commodity.

And of course, even before the panic and the bubble, existing producers had been investing in mines and treatment centers to obtain more rare earth elements; the resultant over-capacity actually ended up hurting some of the late-comers who tried to exploit the bubble. Nonetheless, here’s a case where supply and demand worked and ensured that those in need of rare earth metals could get there hands on them.

China’s apparent monopoly, in other words, was illusory, or at best temporary, and not a threat to global security.