Charlie Hebdo and the quintessentially French art of offensive cartoons

France is home to the Louvre. But if you’re looking for the art that’s closer to capturing the true spirit of the nation, you might be better off buying the latest edition of Charlie Hebdo, the French weekly whose Paris offices were attacked by terrorists Wednesday, leaving 12 dead.

France is home to the Louvre. But if you’re looking for the art that’s closer to capturing the true spirit of the nation, you might be better off buying the latest edition of Charlie Hebdo, the French weekly whose Paris offices were attacked by terrorists Wednesday, leaving 12 dead.

“The attack today was really on a national institution,” says Laurence Grove, a University of Glasgow professor, and an expert on French cartooning.

It’s hard for outsiders to understand the centrality of cartoons in French political and cultural life, where they’re known as the “Ninth Art.” But Charlie Hebdo and rivals such as Le Canard Enchaîné are part of a distinctly French blend of journalism, politics, satire, art and unrepentant provocation known as the Journaux irresponsables, or irresponsible press. To be sure, other countries have cherished comic traditions. (Japan has manga for example.) But France’s cartoon tradition differs in that it is both overtly political and seeks to identify touchy topics that it can skewer mercilessly.

“At Charlie Hebdo, they almost consciously say, ‘What can’t we say?,'” says Grove. “And then they say it.”

While political cartoons have existed for centuries, and indeed cartoons regularly mocked French royalty in the run-up to the revolution of 1789, Grove says France’s modern-day, politically charged cartoons may have grown out of the post-war period. As they battled for the ideological future of the country, left-leaning Communist and conservative Catholic groups produced comics to win over French children to their respective points of view. As they grew up, French kids never seemed to lose the comic habit.

In the 1960s, the form continued to develop, amid the launch of satirical, news-driven cartoon publications. Foremost was the launch in 1960 of Hara-Kiri, a satirical weekly, akin to Mad Magazine in the US, but more overtly political, and often lewd or in egregious taste.

“What these were doing was saying that comics weren’t for kids,” says Grove.

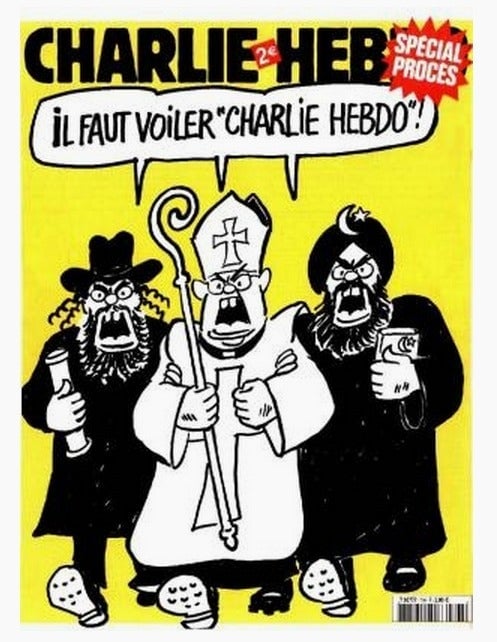

It came into repeated conflict with authorities. The magazine was banned more than once, necessitating name changes. Eventually it morphed into Charlie Hebdo, the paper which was attacked today. While the magazine clearly leaned left politically, it was an equal opportunity offender, lampooning everyone from Corsican nationalists to Catholic clergy along with a steady series of nasty depictions of political players. But in recent years religion has become a reliable area where the magazine was able to consistently stoke outrage, bringing about regular clashes, not just with Muslim groups, but also Christians.

Grove suggests that pushing the limits of taboo is an important component of French political and cultural life.

“The French hold dear to then idea that you might not like what people are saying, but people have a right to say it,” Grove says.