This post has been corrected.

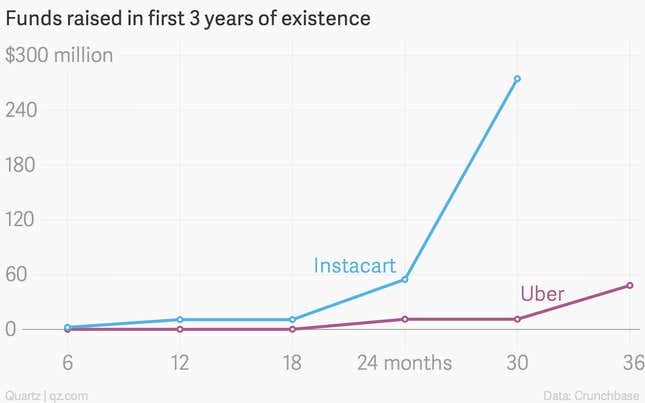

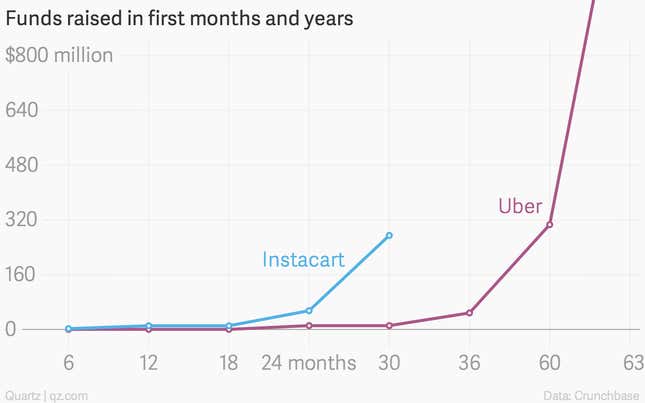

Instacart, the nimble grocery delivery service that’s outpacing competitors like Amazon Fresh and Google Express, was labeled an “Uber for groceries” almost as soon as it was founded in 2012. Two and a half years later, there’s no comparison—at least not when it comes to early-stage funding. Having just closed a $220 million round of financing at a new valuation of $2 billion, Instacart has handily outpaced the notorious car service it’s been compared to.

Funding for Uber didn’t hit its explosive growth period until well after the three-year mark, and after it had expanded internationally. Right now Instacart is in just 15 cities in the US.

Instacart no doubt has the benefit of the tech market being much frothier than when Uber was founded six years ago. And it benefits from the precedent set by Uber, which has shown what can happen when a mobile-first, demand-based business model meets significant scale. But Instacart—dubbed “America’s most promising company” by Forbes this year—also has benefited from something that thus far has eluded Uber: a reputation for playing well with others.

Although in its early days, Instacart would send its personal shoppers into grocery stores without formal agreements from the grocers, the company now sees official partnerships as crucial to its business.

“Our operating model is to partner with retailers,” says Nilam Ganenthiran, head of business development and strategy at Instacart, insisting that the company’s old ways—getting kicked out of Trader Joe’s and delivering groceries from San Francisco Whole Foods stores while Whole Foods was telling the press, “The delivery service that we’re working with is Google Shopping Express, and that’s the only one“—were “proof of concept” trials.

“We believe partnerships with retailers are critical,” Ganenthiran says, because ”we have no expertise in merchandising… partnerships allow us to focus on what we are great at.”

Instacart now has more than 50 official partners, he says, including Costco, Fairway—and Whole Foods.

Cooperation with Whole Foods led to a landmark deal for Instacart in September: a national partner (its first), a platform for testing new service options (Whole Foods is piloting customer pickups of Instacart orders at stores in Boston and in Austin, Texas), and an ability to embed Instacart workers in the stores to speed up fulfillment. The arrangement is panning out nicely for Austin-based Whole Foods, too. Customers buy 2.5 times as much when they order on Instacart than when they shop in the store themselves, Whole Foods says.

Sequoia Capital’s Michael Moritz calls the arrangement a “huge vote of confidence by one of the nation’s most admired retailers.” His firm invested in San Francisco-based Instacart despite a disappointing experience with Webvan, one of the more famous flameouts of the 2001 dot-com crash.

Webvan’s problem wasn’t just that it was ahead of its time. It invested heavily in distribution centers and information systems to essentially replicate the infrastructure of traditional supermarket chains—minus the stores, of course. Instacart has no such aspirations; it doesn’t want to be saddled with inventory.

“We are absolutely not a retailer; we are absolutely not trying to be Amazon.com,” Ganenthiran says. “We are a retailer’s best friend.”

Ganenthiran’s vague description of Instacart’s friends—not grocers, but retailers—channels broader ambitions. Indeed, last week, the company announced a two-city pilot with its first non-grocery partner, Petco, the US-based pet supplies retailer. Though small now, the deal holds significant potential—Petco has 1,300 stores in the US and Mexico.

And that kind of scale will be essential for Instacart to reach its ultimate goal: profits.

Correction: An earlier version of this post listed Kroger’s as a formal Instacart partner. It is not.