In a time of increasing political polarization, it often feels like we live in echo chambers. This was apparent when, as I wrote for Quartz, people discussing Ferguson on Twitter fell into a “red group,” whose members were more likely to be conservative and support the Ferguson police, and a “blue group,” whose members were more likely to be liberal and African-American and support Michael Brown. The two groups rarely spoke to each other and were often hostile when they did. Many people told me they found this depressing but unsurprising; it sometimes seems like internet incivility has become so prevalent, social schisms so profound, that if two groups disagree on a controversial issue like race, they are better off not communicating online at all.

But I want to discuss a recent and more hopeful counterexample: a discussion of race in which different social groups expressed contrasting but non-opposite views, information spread from one group to another, and criticism produced a productive response. A few weeks ago I received an email from Gilad Lotan, an expert on how information spreads (or doesn’t) across Twitter’s chasms. (He has mapped everything from the discussion of Israel and Gaza to the rumors of bin Laden’s death.) He had been studying #CrimingWhileWhite, a hashtag which exploded on Twitter a few days after a grand jury decided not to bring charges in the case of Eric Garner, an unarmed man who died in a chokehold from an NYPD officer. In response, white people began chronicling the things the police let them get away with:

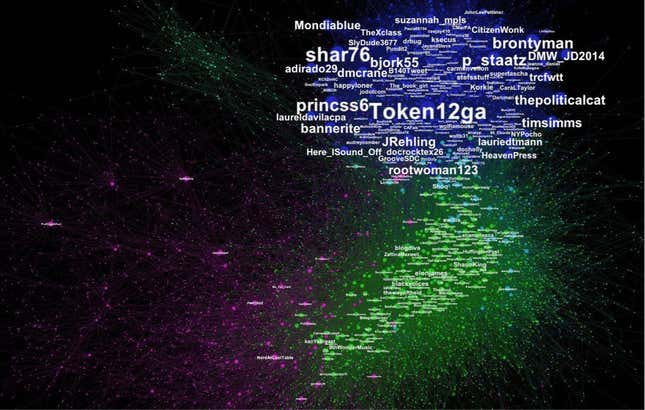

Lotan produced a social network mapping the people using the #CrimingWhileWhite hashtag. In the picture below, each circle represents a Twitter user; two users are connected if one follows the other. Larger labels indicate users with more connections, and the color of the circles represents communities that are more interconnected.

I was immediately intrigued. Who were the blue and green groups? Were they the same blue and red tweeters I had found in my Ferguson analysis?

As it turned out, they weren’t. Like the blue Ferguson group, the blue #CrimingWhileWhite group tended to be made up of liberals: they described themselves using phrases like “#uniteblue” (a liberal hashtag), “progressive,” “liberal,” and “Obama.” But the green group was very different from the red, pro-police Ferguson group. I recognized many of the central figures in the green cluster —@elonjames, @blackvoices, @shaunking—because they had supported the Ferguson protesters. The green tweeters were also more likely to describe themselves as black or African-American.

Importantly, the blue and green groups did not show the same diametric opposition in what they tweeted that the Ferguson tweeters had.

While the groups are expressing ideas that are somewhat different—the blue, liberal tweeters are more likely to mention well-known conservatives like Rudy Giuliani, Cliven Bundy, and Shaun Hannity—they are not saying opposite things as the Ferguson tweeters were. They even share one of their most common tweets, in which someone confesses stealing a car.

After #CrimingWhileWhite spiked, many commentators pointed out that the hashtag failed to tell the more important side of the story: it focused on how good things were for white people, not how hard things were for black people. And at least some of the #CrimingWhileWhite tweeters were willing to listen: for example, one prominent #CrimingWhileWhite tweeter wrote a Facebook note saying that she didn’t want #CrimingWhileWhite getting all the attention when black men were dying.

In response, Jamilah Lemieux started #AliveWhileBlack:

This spread very quickly: within about five minutes, several black tweeters had responded with experiences that got hundreds of retweets. Other tweeters called on prominent black tweeters to add their voices, and some, like actress Kim Coles, quickly responded.

The first nine widely re-shared tweets were posted by black tweeters. About eight minutes after the original hashtag began, though, a white tweeter, posted:

Forty-two minutes after the hashtag began, Danny Sullivan (founding editor of MarketingLand), who has nearly half a million followers, first retweeted:

and then added his own broadly shared tweet:

I am not saying that all this represents some perfectly harmonious discussion of race: I’m sure there were people who completely ignored #AliveWhileBlack, people who responded with unconstructive vitriol to #CrimingWhileWhite, and trolls who spit nasty things at both. But this seems a lot more constructive than the Twitter discussion of Ferguson. When people criticized #CrimingWhileWhite, at least some #CrimingWhileWhite tweeters responded, and while #AliveWhileBlack was started by black tweeters, it soon spread among white tweeters as well.

So why does this discussion appear more productive than the Ferguson discussion? Here are two possible reasons:

- #CrimingWhileWhite and #AliveWhileBlack began after the Eric Garner grand jury decision, which was less politically divisive than the Ferguson grand jury decision. While conservatives were more likely to support the Ferguson grand jury decision, both conservatives and liberals criticized the Eric Garner decision: Fox News described it as “totally incomprehensible” and “a grievous wrong.” The fact that people were united across the political spectrum may have produced less rancorous discussion.

- More importantly, the people participating in the #CrimingWhileWhite/#AliveWhileBlack discussion were more politically homogenous than those participating in the Ferguson Twitter discussion. It wasn’t that the Ferguson red group and blue group magically reconciled; the red group didn’t appear in #CrimingWhileWhite network at all. (In the Ferguson data, I saw roughly equal numbers of tweets from self-identified liberals and conservatives; in the #AliveWhileBlack data, liberals tweeted about six times as often as conservatives.) So it’s not that the crevasses in Twitter have disappeared; we’ve just zoomed in on part of the terrain.

This is not a terribly optimistic reading of the story. But there are no easy solutions to the echo chamber problem, and it’s important to remember that when a discussion seems united, it may well be because those who disagree just aren’t participating. (It’s also possible those who disagree with a hashtag do comment on Twitter but don’t tag their posts with the hashtag).

After the Ferguson grand jury decision, Twitter made our bitter divisions plain. During #AliveWhileBlack and #CrimingWhileWhite, Twitter appeared more united. In some ways, the discussion truly was more productive: information propagated between different groups and people responded to criticism. But in some ways the unity was illusory, the harmony merely a lack of red tweeters. We need more than agreement: we need fierce but productive dissent. Otherwise, our peace is merely that at the eye of a hurricane.