“Building a New Greece” was the hopeful title of an investment conference held in New York on Nov. 29. Its timing was fortuitous; the agreement earlier this week on its debt-reduction targets, Greece hopes, will be the icing on the cake for potential investors, and the event bustled with businesspeople and government ministers trying to make the case that the threat of Greece leaving the euro zone—a “Grexit”— is now over and the time to invest is now.

It is true that the recent deal, which relaxes the payback terms on Greek debt, has somewhat alleviated the risk of Grexit. The EU’s leaders seem to recognize that such a scenario would cost Europe more than paying to keep Greece alive. And there is a certain logic to making investments now, particularly if you’re a speculator. “You get very, very cheap companies, cash-starved companies,” explains Capital Partners President Petros Doukas.

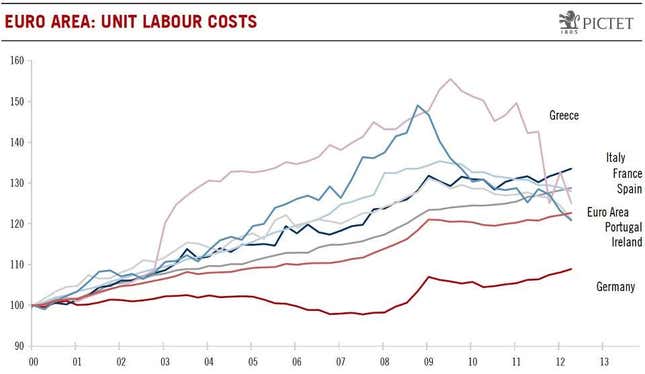

At least in comparison to a few years ago, those companies look more sustainable. Unit labor costs—really, the primary expenditure of most businesses—have declined dramatically, faster than in any other country in the euro area and much of it in the last year. Other capital expenditures—pensions and benefits, in particular—have also been slashed by new austerity regulation. Admittedly, that’s not great for the Greeks, but it’s great for business.

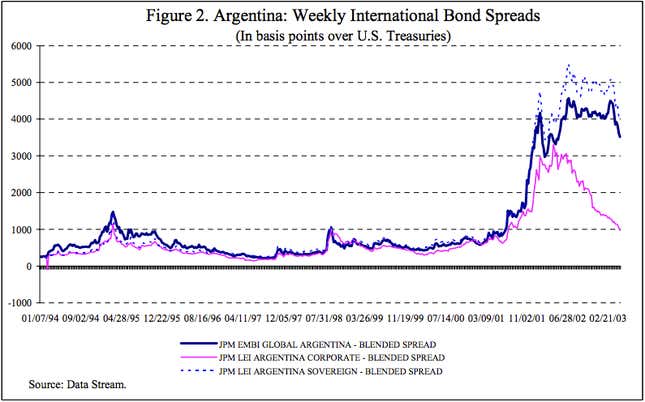

More compelling is the trading case. Some hedge fund managers—many of whom have already loaded up on Greek government (sovereign) bonds after Greece’s March default—explain that defaults have historically worked the same way: the government recovers (as investors become more confident the country won’t default on them again), then corporate bonds recover (as the likelihood that corporates will default likewise declines), then equities and prospects for future growth increase. A bond recovery doesn’t necessarily mean that companies who issue the bonds will do well; it just means the risk of their defaulting goes down, so investor demand for their bonds goes up, so the price rises, so anyone who bought into the bonds early on will see a profit.

So, if you’re willing to take a certain amount of risk, then buying up Greek corporate debt might not be such a bad idea, say some hedge fund managers who were at the investment conference. They cite patterns witnessed in Argentina’s default, which officially took place in early 2002. After Argentina defaulted, corporate bonds immediately recovered, as companies’ existing debts became far more stable. Speculators who bought up that debt for cents on the dollar in the year or so after the default were soon rewarded—either they sold it again in the secondary markets two or more years after the default or they waited for the bond to mature and got the full face value of their paper.

Buying up bonds now must take into account that things are so bad in Greece that they can’t get much worse, which is still a hard reality to accept. Speculators looking at defaults on a historical basis, however, could be ready to make that bet. Those who can, however, will want to make sure that debt is governed by foreign law and denominated in euros, just for good measure.