Every government has been commanding women to breastfeed. Brazil tried bizarre ads of a baby’s nose looking like a nipple. New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg famously asked hospitals to keep formula under lock and key, sanctioned only by nurses so new mothers try harder to breastfeed. Similar efforts in the Philippines achieved remarkable success: exclusive breastfeeding rose from 36% in 2008 to 47% last year.

But these official overtures are largely focused on a baby’s first days of life. What happens afterward? Or when Mom goes back to work?

Even with the best of intentions—and none of the inevitable challenges like getting the latch right—exclusively breastfeeding a baby is pretty formidable. It’s a battle against biology; a mother’s milk supply dwindles when away from the baby. The only way to keep it up is to express milk at the same times that the baby would normally feed, generally every three to four hours. This can be done manually but is most efficient with an electric pump that relies on horn-like devices cupped over the breasts to suction the milk. It drips out slowly—emptying one breast can take as long as 20 minutes—into a bottle attached to the horns, which is then refrigerated or frozen for baby’s later consumption.

I explain this in detail because many adults, men and women, don’t really understand the mechanics of breastfeeding or pumping. Nobody ever discusses it honestly during school health courses or around the water cooler or obstetrician’s appointments or even childbirth class. I learned the way most people do: by having a baby. I nursed my eldest for two years and am still doing so for my baby, who turned 1 last week. Once I became a pumping mom, I felt shocked and betrayed by how slow, laborious, secretive, low-tech, and difficult it all seemed—often for a measly few ounces. Let me be more explicit: To be a mother employed outside the home and exclusively offer breastmilk to your child, you constantly have to keep an eye on the time and your output (both milk and work)—and to pray you can meet the baby’s ever-changing needs. It is like having a whole other job.

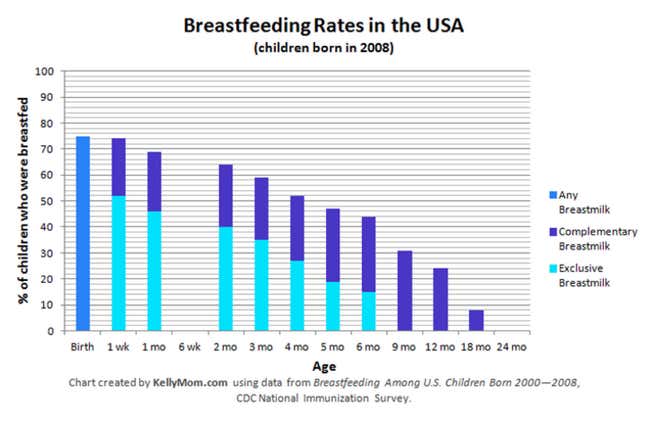

Most mothers eventually supplement with formula, and by six months of age, just 16.3% of US babies are exclusively breastfed (pdf). The older a baby gets, the less likely she is to be breastfed, as this chart shows:

The lucky toil in places with a lactation room: Luxury is a glider or rocking chair, a table to lay all the parts out, and a sink to wash them. Most of us settle for a small room with an outlet and a lock on the door. US law actually requires companies with more than 50 employees to give mothers adequate time and space to express milk at work.

And this would be fine if a modern woman’s place was just the home and the office. Yet we know that’s hardly the case. We juggle among client sites and shopping malls, we fly to meetings in Tuscaloosa and trade shows in Tokyo, and we nurse our babies even as we nurse aging parents in hospitals and retirement homes.

Yet in its efforts to encourage women to breastfeed, government conveniently sidesteps one thing it actually can control: Building codes. Why force a woman to get medical permission to feed her newborn formula but abandon her three months later when she’s in transit at JFK International Airport and needs a place to pump?

It’s too easy to force the burden of nurturing a child on women alone—to make breastfeeding their problem rather than society’s. Critics would say mandating lactation rooms is unnecessary government intervention. I imagine they would feel differently riding an elevator that hadn’t been inspected in 37 years. If we are serious about increasing rates of breastfeeding—something every government claims to be—then it is absolutely imperative to make pumping easier and accessible for working mothers.

Based on three years (and counting) as a nursing and pumping mother, and countless conversations with counterparts across the world, I suggest these seven places as the next targets of the global breastfeeding campaign.

Hotels and conference centers. Here’s a discussion thread from a mom fretting about where to pump as she attends a meeting at a New York City hotel. “Worst case scenario, I pump in a bathroom and carry the milk around all day. … The other alternative is to ask a co-worker to let me use their hotel room (awkward!).” Organizers of large conferences should start forcing venues to accommodate working and nursing moms, or else find a private space and make their existence and purpose known to attendees through conference brochures and websites.

Airports and airplanes. Architects and planners are putting more playgrounds and family areas in airports, but they haven’t quite caught up to the needs of working mothers. Consider this mom who was directed to the nursery at Los Angeles International Airport only to find “it’s just a family bathroom, without any outlets! I freaked out! I also forgot to bring my battery pack. … I was just going to pump in the regular women’s restroom since I saw an outlet in there. When I took my pump in, I realized I was able to plug the pump and pull it under the handicap stall, so I pumped there, standing half the time and squatting the other half.”

And if a woman is on a business trip and a flight takes longer than a few hours, chances are, she’s going to need to express milk. It’s hard enough to brush your teeth in one of those plane stalls; imagine pumping in one.

Large companies. Most of them offer lactation rooms for employees but the rules are not so clear for visitors. I was recently a speaker at an organization that employs nearly 10,000 people, and my “handler” for the day was a young lad who had no idea what I needed when I asked for a place to pump. I ended up in a bathroom that had no outlet. Luckily, I was prepared with my battery pack, but the environment was less than ideal, not to mention less than sanitary. Still, anybody who would potentially interact with mothers (yes, that would probably be every worker in an organization) should be better prepared to address its lactation policies.

Malls, theaters, museums and restaurants. My fellow nursing mothers in New York City likely know the location of every Babies R Us—each branch of the children’s retailer has a nursery ideal for pumping. What strikes me every time I use it is that I am never alone. It makes the case for “build it and they will come.”

The same should be applied to malls (especially if they want female customers to spend more than a few hours there) and places where women might like to enjoy a night out with their partners (i.e. theaters and restaurants) or a day out with older children (zoos and museums). To be sure, I feel less strongly about the government forcing pumping places into these locations, but I think it makes very sound business sense.

School, colleges, houses of worship. Two women in my playgroup implore the inclusion of church on this list, which surprised me, because I figure this is a place you wouldn’t be apart from the baby. Apparently not all services are child-friendly and some worshipers are uncomfortable with babies nursing in public.

Similarly, teachers at public schools tell stories of pumping in supply closets, bathrooms, and locked classrooms while the children are out. This seems especially egregious given the large numbers of female educators. I’d also make the case to create spaces for parents to pump as they juggle meetings, chaperone field trips, or volunteer at the bake sale for an older school-age child and leave the baby at home.

College campuses, too, attract a mixed population—students, adjuncts, visitors, speakers—with many a nursing mom among them. Good luck finding a public place to pump there.

Rest areas along the highway. Basically, lactation rooms need to be seen more as a public utility and less as a luxury offering. Working, nursing mothers who go on frequent business trips usually have a car adapter for their pump but it is actually hard to find a safe, private place to do this. When my first child was six weeks old, I had a speaking engagement at the University of Virginia. I found a glorious spot overlooking the Shenandoah Valley and began pumping—only to be joined within minutes by a half-dozen tourists unexpectedly taking in scenery of a different kind.

Hospitals. Oddly, this is usually the first line of battle as the state encourages new mothers to breastfeed but move a few floors above or below labor-and-delivery and it’s a different story. Try asking a hospital if it has a place to pump, as I did this past spring when my mother had heart surgery and lots of complications. In between tending to her and dealing with doctors and nurses, I pumped in waiting rooms, intensive care units, public bathrooms, patient bathrooms, parking garages, and most often, by her bedside. At times, doctors mistook the suctioning sound of my pump for one of her machines. It was comical and I am hardly easily embarrassed (most of us who make it this far can’t be), but there must be a better way.

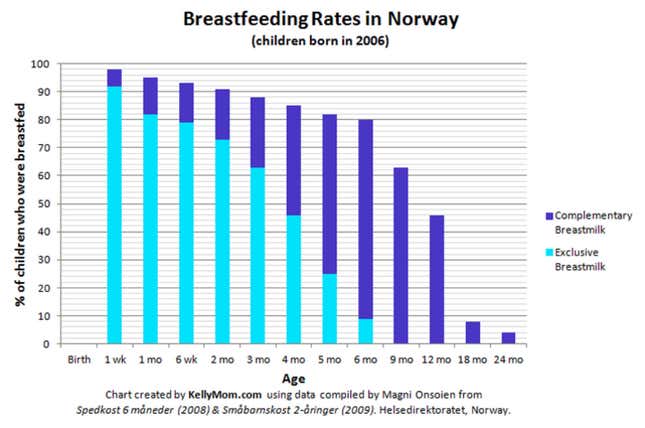

Some countries have especially strong track records on supporting working women’s desire to breastfeed. Norway offers working mothers two hours off per day to nurse, either at the office or at home. Here’s its breastfeeding success story:

In Tanzania, where my college roommate now lives, some breastfeeding mothers bring their nannies and babies along with them to conferences. The nannies stay with the baby elsewhere during meetings, and the mother leaves as she needs to nurse. When it comes to pumping, though, Japan seems a better example for the US to emulate. Cynthia Nowak, a mother of two who lives in Seattle, recently traveled there and was impressed with its breastfeeding culture. Granted, few women do it in public but the result is that all the “nurseries,” as they’re known, double as a place to actually feed a child or express milk for him. Among her most memorable mother-friendly places: the “tourist center in Asakusa. I was shocked as it’s not a big city, but a big tourist draw. They had two private rooms with comfy chairs, tables and outlets. In the larger room there was a changing table and sink.” And, she adds, the “Narita airport has a huge room with comfy chairs and a long metal sink. …. There was plenty of room to wash your child and dry him off on this clean, seemingly sterile surface.”

It doesn’t seem like much to ask for: a clean room with an outlet. A table, a chair, a lock on the door, maybe some universal signage outside to let women know where they can express milk (Japan uses a tipped baby bottle as its symbol). Surely, a combination of the public and private sectors can figure out ways to provide the space so that women can provide the most basic necessity to their babies. Consider that 55.8% of women with babies under age 1 work outside the home, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics notes those mothers are “less likely to be in the labor force than mothers with older children.” Maybe that’s by choice, but we must work harder to ensure it’s not by design.