“My father had a true revolutionary spirit that continues to inspire and empower people of all ages and ethnicities,” Cedella Marley, music legend Bob Marley’s oldest child, who is also a singer, dancer, actress, fashion designer and the CEO of the Marley Family recording label Tuff Gong, told me recently in reflecting on her father’s legacy. “The message of the music doesn’t have an expiration date. Every generation is hearing it with fresh ears and connecting with the music in a new way.”

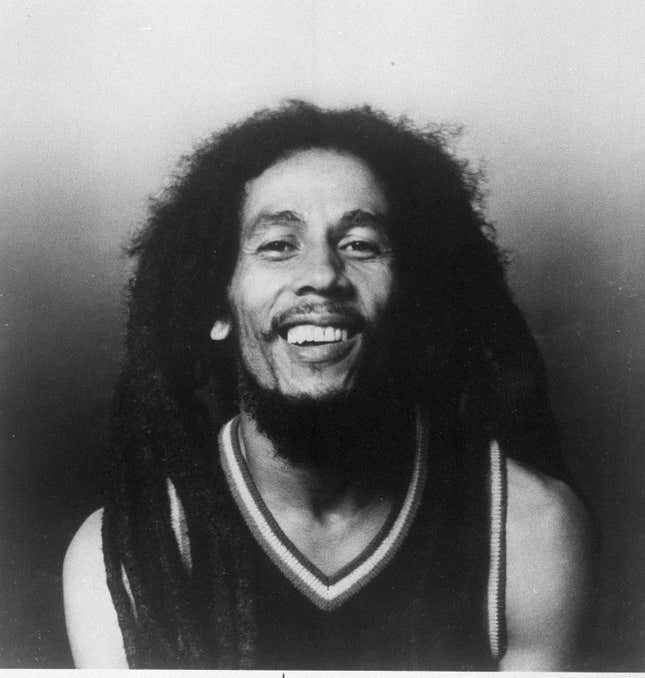

Bob Marley, who died in May 1981 after a battle with cancer, would have turned 70 this month, on February 6th, but his music is more present than ever. The most followed deceased entertainer, with more than 70 million Facebook followers, not to mention a healthy series of business enterprises bearing his name, Marley’s message of both peace and revolution continues to speak to people of all backgrounds.

“At any time, you might find a teenager in the Midwest listening to Bob, or a retired couple jammin’ to the same track on their boat in the Caribbean, while a teenager in Ghana is listening to his every word,” Cedella says.

“People think that the most famous musician in the world, or recognized musician, might be John Lennon or Bono or Mick Jagger or something like that, but it ain’t,” says the filmmaker Don Letts, who knew Bob Marley during his days living in the UK in the late-70s. “Trust me. It’s Bob Marley.”

Marley’s biographer, the author of the fantastic Bob Marley: The Untold Story, Chris Salewicz, agrees.

“In the US and UK Bob Marley may have been taken up by the middle-class as a slightly ‘right-on’ symbol, but in developing countries he is sincerely considered a voice of protest and righteousness,” Salewicz says. “After all, in China you don’t really hear Bruce Springsteen, but you will hear the songs of Bob Marley. Hopefully he is also those things to his more affluent fans in the west. But I’m sure that Bob would be extremely happy that his message is so felt so meaningfully across the entire planet.”

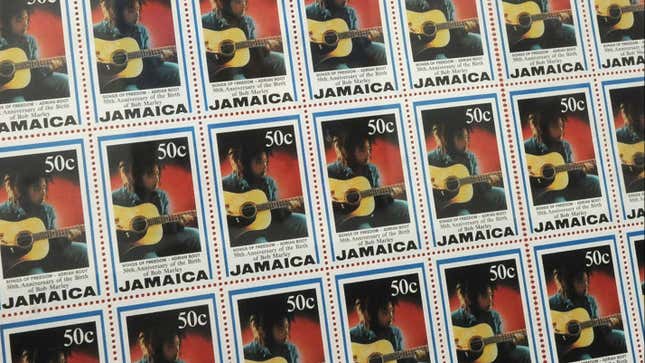

Long before the music industry hit the skids and artists were forced to look beyond recording and touring revenues for income, Bob Marley’s family, faced after his death with an artist that was no longer active in either of those areas, sought other ways to get Marley’s message across. It began with the 1984 multi-million selling, many times reissued and repackaged “best of” compilation Legend, which has sold millions across the globe, many of those in parts of the world that are typically parochial in their tastes. It has since branched into everything from the typical (T-Shirts and mouse pads) to the more unusual (the new Marley Natural brand of cannabis-related products). While each is in line with the broad, if uncompromising and nonconformist, approach the performer took during his lifetime, the basis of his popularity remains where it all began: In his music, like the excellent new archive release Easy Skanking in Boston 1978.

As for why Marley’s message continues to speak to millions around the globe, Letts doesn’t hesitate.

“He spoke to the oppressed and the downtrodden,” Letts says. “In other words, he still speaks to 90% of the planet. Bob’s messages are more important now than they ever were. For every one of those middle-class white guys or girls playing ‘One Love’, there are a million more around the world who are playing ‘Get Up, Stand Up’.”

Bob Marley was born in the countryside of Jamaica, to a young, local mother and a wayward, white, British father, whom he hardly knew. Fascinated with and drawn to music from an early age, Marley began seriously pursuing a career after his mother moved them to the ghettos of Trenchtown, in Kingston, Jamaica. He soon fell in with two young, aspiring musicians, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, and made a series of increasingly successful local records with the band that eventually morphed into The Wailers.

Ever artistically restless, and feeling taken advantage of financially, Marley, Tosh and Wailer formed their own label, and eventually connected with reggae pioneer Lee “Scratch” Perry.

“A lot of people—purists—say that his albums with Scratch Perry, done in the late 60s, are Bob’s best records,” Salewicz says. “I think they are, actually. They’re sensationally good. When I first heard them I couldn’t believe how good they were. Tunes like “Mr. Brown”, “Duppy Conquerer” and “Johnny Was”, for example, are just fantastic. Absolutely great records. They seem to flow perfectly. There’s a mood about the sound, and spontaneity at the same time, but I’ll tell you what’s different about the Scratch songs: Bob’s singing. There’s this little, almost unknown detail, which is that Bob had singing lessons from Scratch before they recorded. If you listen to Bob’s voice on previous stuff and then you listen to the songs with Scratch, you hear a distinctive shift.”

While Marley was scoring hits in his native Jamaica, he was searching for a sound to reach the masses.

His next stop was the UK, where he connected with Island Records’ chief Chris Blackwell, who gave Marley and the Wailers £4,000 (about $7,000), much to the chagrin of some of Marley’s bandmates. The Wailers turned in an album not that far from what they’d been doing with Perry (you can hear the band’s original mix on the deluxe version of the band’s Island debut Catch A Fire), which Blackwell promptly overdubbed English musicians onto and remixed. It did the trick, however.

“Catch a Fire was my introduction to Bob,” Letts, who was a teen in the UK at the time of its 1973 release, says. “He came along at a time in my life when I was struggling with identity. I’m what they call first-generation British born black, which kind of rolls off the tongue these days, but back in the mid-70s it was a very confusing concept. Bob came into my life at the perfect time to kind of show me and helped me to be all I could be without compromise, and like many people of my generation who were at the forefront of the punk movement, that was very powerful. Bob didn’t anglicize or Americanize himself. Like James Brown before him, he did his thing and people either dug it or they didn’t. Luckily for Bob, for the most part, they dug it.”

Marley’s son Ziggy agrees, but also gives credit to the musicians Marley surrounded himself with.

“Bob and the Wailers were very influenced by James Brown and Curtis Mayfield and the stuff that was happening in the ’60s,” Ziggy Marley says. “They were influenced by a lot of what was going on in America, but they twisted it in such a way that they weren’t imitating it. They used it as a point of reference, but these guys were intent musicians. They were musicians not in terms of technical education but in terms of listening and understanding sounds, spaces, and how things drop and the way things fall. It’s very interesting, Bob surrounded himself with great musicians but I believe one of the most important things was that they all believed in the same thing. They all believed in a certain philosophy and way of life. They were a unit. They were a tight unit who had the same ideas, the same kind of way of life that they wanted to live. One guy wasn’t running off doing one thing and another guy running off doing another. That created a very tight, together sound. I think that was very important. It’s hard to find that today, where a group of guys are just able to work like that and have the same feeling about things. There’s much more to these guys than we sometimes give them credit for.”

Letts points to the multilayered message of Marley’s records, as well.

“The thing about Bob is that he had this duality,” Letts says. “He was the lover and the fighter. He could make you move your hips, but he could kind of tool you up for the struggle as well. In the 21st century, the kind of revolutionary Bob has been castrated in favor of the more pop, user-friendly aspects of what he was about. I find that very frustrating. People don’t realize that Bob was a revolutionary man. He fought with music.”

Ziggy Marley is quick to pick up on Letts’ point when I share it with him.

“A lot of people would like to condense him to the idea of love and peace,” Marley says of his father. “But Bob is deeper than love and peace. Those were things he spoke about and sang about, but they weren’t the only things he spoke about and sang about. Bob was a revolutionary. He was a person who wanted social justice in a real sense, in a real physical sense. There’s a lot more to it than the whole ‘Bob Marley, love and peace and smoke weed.’ That’s not it at all. No. It’s deep! It’s all right for some people to pass it off as that. But it’s much deeper. And the message is always relevant. ‘Get up, stand up for your rights’? ‘One love, one heart, let’s get together and feel all right’? It’s all still very relevant.”

“Get Up, Stand Up”, written with Tosh, began a long string of anthems that took hold with a growing following of fans in the 1970s, and that are now internationally known classics. Ziggy Marley seems certain that his father’s ever-evolving, uncompromising artistic output that is at the heart of the resilience of his catalogue over the years.

“For me, and I’m sure for many people, the music is so consistently impactful,” Marley says. “The album Survival and tracks like ‘Africa Unite’, that was my awakening of my Afro-centric, militant, rebellious part of me. And Kaya, too. For me it’s not songs, it’s albums. When I listen to my father’s music, I don’t listen to it in terms of songs. I listen to it in terms of albums.

“As things progressed over the years, Kaya (released in 1978) sounded so different, the mix and the sound of it,” Marley goes on. “There’s something about that album. The sound is just very eerie and misty and sexy. It’s nice. I like that. ‘Is This Love’ is on that album. A great song. Then there are other songs, like ‘Concrete Jungle,’ that have such a heavy sound. And ‘Burnin’ and Lootin’.’ That song has such an intense reality to it. But that album wasn’t that well-received by critics, who thought that the album was like a sell-out and not reggae or roots enough. But I like that, because Bob does what he wants to do. Bob’s music is Bob’s music. You can’t really nail it down to roots reggae or something. It’s Bob’s reggae. Bob has his own sound. In the world of reggae, Bob’s reggae sounds different than another reggae artist’s. It doesn’t sound the same.”

Cedella Marley sums it up well.

“I think the words are just as applicable today as they were when he wrote them,” she says of her father’s message. “If he were here today I’m sure he would continue to try and encourage the world to unite in peace and justice.”

“Bob Marley—like Joe Strummer or Bob Dylan or John Lennon – he wasn’t one-dimensional,” Don Letts says. “He wasn’t a caricature. He embraced the range of human emotions. Sometimes you had to fight, but you also had to sometimes know when to stop fighting and make love. The truth of the matter is that rock and roll in the 21st century has been castrated. It’s hard to find people that have any kind of opinion these days. I’m not talking about going out and throwing a Molotov cocktail, I’m just talking about engaging in a dialogue that’s not just about selling product. That’s what’s missing. The legacy of Bob is an example of how you could do that without standing on a soapbox. It’s funny that no one seems to have picked up the ball and run with it in the 21st century. Rock and roll is becoming increasingly safe and conservative. That dismays me. I’m a product of and a great believer that music can change your life, not just your sneakers. It certainly changed mine. Back in my day, we got into music to be anti-establishment. Now, a lot of people get into music to be part of the establishment. If that’s your goal, if you want to walk the red carpet, how radical can you be? It’s a problem, a big problem, I’m telling you. The youth need to reclaim music. It was the soundtrack of young people. It wasn’t the soundtrack of consumerism. That’s why Bob’s music stands the test of time.”

“I know that a lot of people think they know so much about him, but as his son, I can see what he went through internally with his music and with his life,” Ziggy Marley reflects. “There’s a lot of glory, but it was not his glory. There were battles. There were struggles. There were indecisions and decisions. There was a lot going on that was going on at the time and that a lot of people might not even think about. For them he’s just a great legend; Bob Marley the legend. There’s a lot more that went on and that goes on, you know? I mean he used to work very hard. And I think he would kind of sacrifice himself. He was like one of those John the Baptist types of people from history, sacrificing himself for his cause, for his message. He was that figure for his time. For the modern time. He was totally obligated to the idea that what he was doing was a mission from God. It wasn’t like something that he thought he was just making up to believe in. For him it was true. It was real. It was not fantasy. For us it is real, too. In his time, and for me, that is what he really represents. It’s even bigger than the idea of the legend. There’s a bigger thing to that that I see. I hope others see it, too.

“What we see in the world today is a lack of leadership in the direction that is positive for the world,” Ziggy Marley continues, as we wrap up our discussion, seeming to again pick up on Letts’ thoughts on the state of the world and the lack of authentic, new artists carrying a meaningful message that might carry on after their careers are over. “In every aspect of the world–political, religious, social–we have people who are leading people in a way that causes the world to be the way that it is. The people need direction. But not from those sorts of leaders. Then they can offer the children direction. Otherwise the parents direct the children in the wrong direction, and we have the world the way that it is today.”