The latest sign that China’s financial system is facing a cash drain

This post has been corrected.

This post has been corrected.

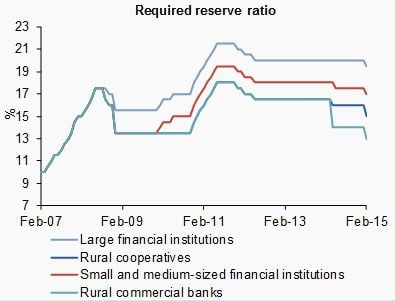

The People’s Bank of China just cut the reserve requirement ratio (RRR) for banks—the percentage of deposits that banks must set aside in case of financial distress. The first broad cut to the RRR since May 2012, the reduction effectively frees up as much as 600 billion yuan ($96 billion) for banks to loan, according to Capital Economics.

The move came as a surprise; while economists had expected an RRR cut at some point in 2015, most didn’t expect it to come so early.

While some point to slowing growth, the more likely cause for the cut has to do with liquidity. Or to put it another way, there isn’t enough cash in China’s financial system.

Where might this money be going?

Out. December data shows the biggest volume of capital outflow since December 2007:

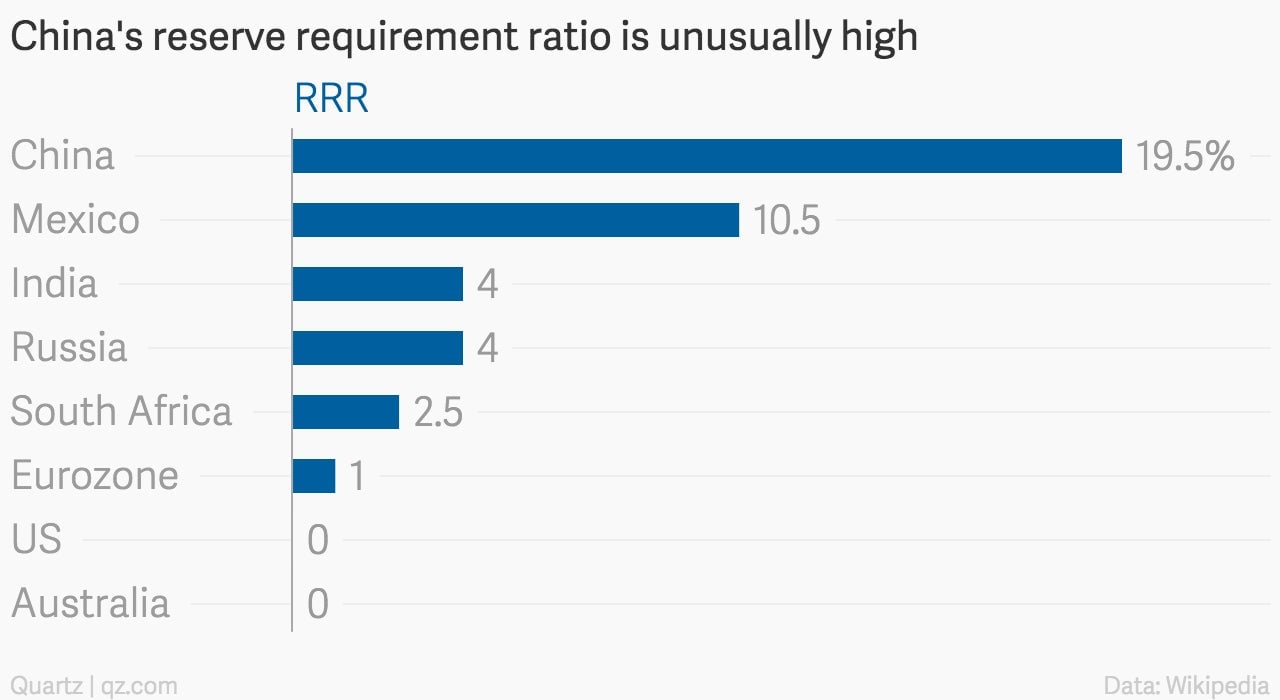

To understand what this has to do with the RRR, it’s important to understand why China’s is unusually high.

China’s economic growth model is not export-led, as is commonly assumed, but rather, investment-driven. This model has created the longest sustained period of high growth perhaps in history—37 years and counting. The engine for this is simple: Chinese savers are forced to subsidize cheap loans to (mostly state-run) industrial companies. In recent years, that lending has shifted toward property developers as well.

But maintaining cheap exports is still critical to the Chinese state. The sector supports millions of manufacturing jobs. And because forcing savers to pay for industrial policy discourages consumption, if the PBoC didn’t rig the currency to make exports cheap to foreign consumers, Chinese households sure wouldn’t be able to buy all those goods. Jobs would vanish, and the unemployed masses would riot in the streets. So the PBoC cheapens the yuan, buying dollars off exporters (and outside investors), and paying them more yuan than it should.

If those extra yuan gushed into the system, soaring inflation would threaten Party stability. So the PBoC does two things: It “sterilizes” money inflows, forcing Chinese banks to buy its bonds, and keeps the RRR unusually high, preventing them from loaning out the extra money it prints.

These policies are pillars to China’s financial stability as long as more money is flowing into the country than out. When that trend flips, the Chinese government has much less control over money flows than many realize.

First, liquidity gets dangerously tight—and since so many Chinese companies depend on banks rolling over their loans to stay afloat, a sudden disappearance of liquidity risks forcing mass bankruptcy.

It gets worse, though.

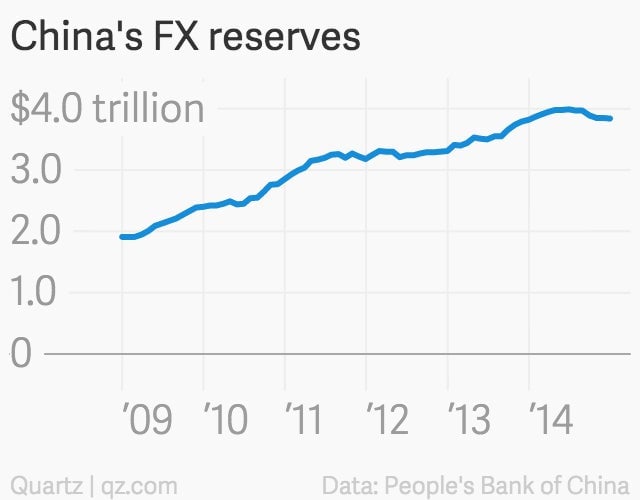

Capital outflows cheapen the yuan relative to the dollar. That’s scary because it shatters confidence in China’s economy, but also because Chinese companies have borrowed heavily in dollars—more than 80% of China’s registered debt is either in US or Hong Kong dollars (the latter of which is also tied to the greenback), as Chen Long, economist at GaveKal, notes. In order to prevent the yuan from shedding value, the PBoC has been drawing down its $3.8 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves—selling greenbacks to boost the yuan’s value. The problem is, buying yuan drains even more liquidity from China’s financial system.

The PBoC has to cut the RRR in order to replace the money that has already gushed out of the system, notes Patrick Chovanec of Silvercrest Asset Management.

China’s financial accounts are too opaque to know exactly how severe the outflow is. But for a country already hovering on the brink of deflation, any big sudden disappearance of money is ominous.

The feature image is by Flickr user David O’Hare (image has been cropped).

Correction (February 3, 2015, 3pm EST): A previous version of this article ran under the headline “The latest sign that China is running out of cash,” which we’ve changed because it’s not strictly accurate. China officially has lots of cash; it added 123 trillion yuan in 2014. What its banks appear to be struggling with is liquidity, the cash that’s readily usable. The PBoC has been furiously injecting liquidity into the financial system using a range of different tools—for instance, GaveKal’s Chen Long notes that the outstanding amount of liquidity created through the medium-term lending facility is now as much as 820 billion yuan. And yet these strategies haven’t worked: borrowing costs remain doggedly high. The amount of liquidity it is now taking the PBoC simply to keep those costs from rising suggests that a high percentage of new loans are going to cover old debts. Also, tighter regulation of the interbank market, and hence shadow banking channels, is likely adding even more liquidity stress. The RRR cut seems more narrowly focused on offsetting the liquidity recently lost from capital outflow and by the PBoC drawing down its reserves to defend the yuan.