Wretched trade data reveal China’s dangerous balancing act

China-watchers know the country is hitting a rough patch right now. But they evidently didn’t realize just how rough—judging by the astonishment that met the customs agency’s Sunday announcement of January trade data.

China-watchers know the country is hitting a rough patch right now. But they evidently didn’t realize just how rough—judging by the astonishment that met the customs agency’s Sunday announcement of January trade data.

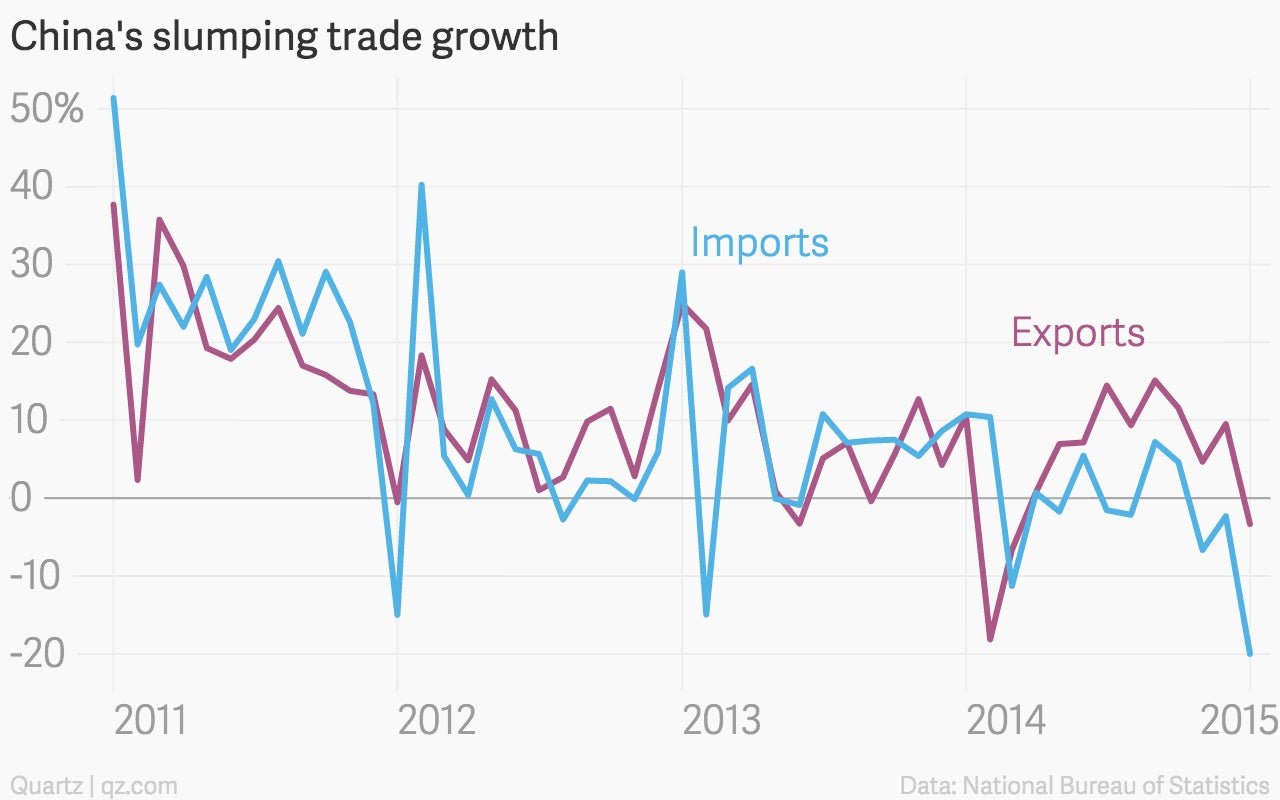

While China exported 3% less in value than it did in January 2014, growth in imports plunged a gut-churning 20%. Analysts didn’t see it coming; most predicted expansion in exports and only a slight import slowdown.

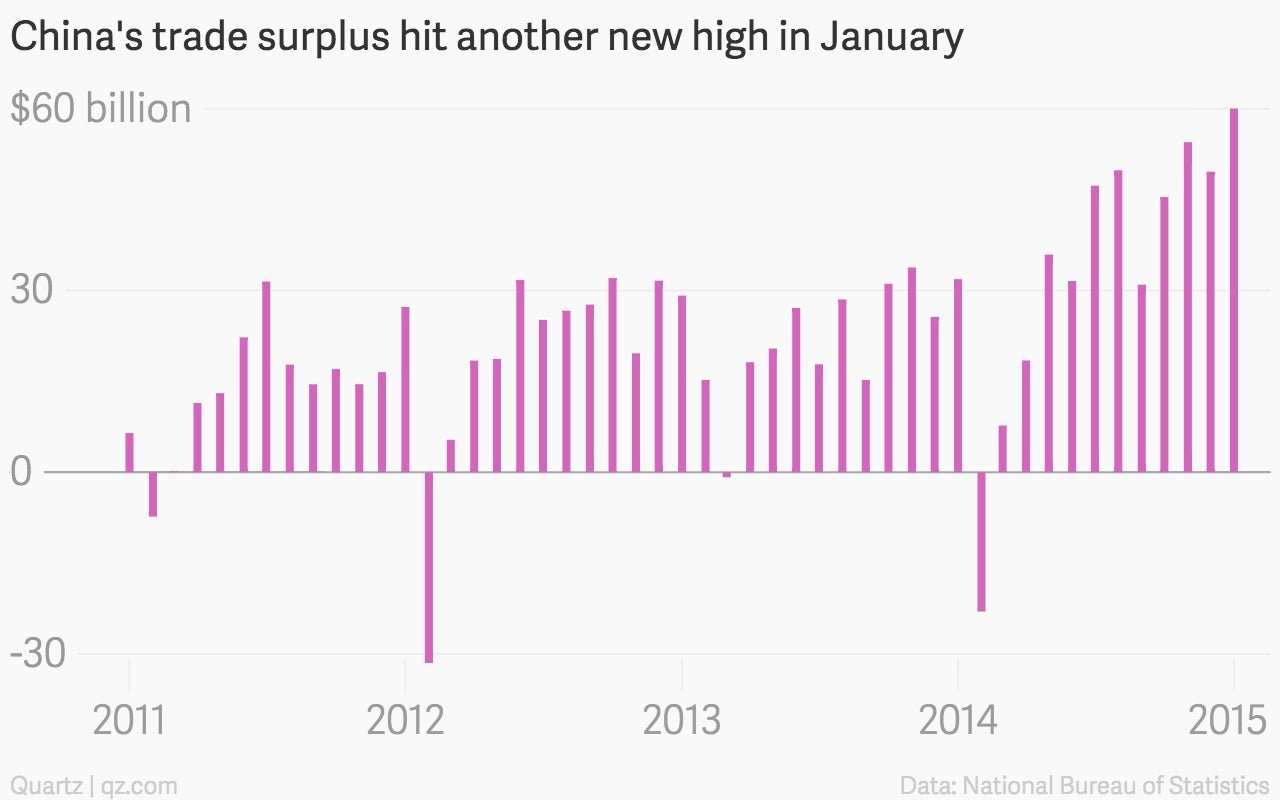

The import implosion in particular drove China’s merchandise trade surplus to a new monthly record of $60 billion.

China’s customs agency blamed the shocking drop in exports on the relatively late arrival of Chinese New Year, which starts on Feb. 19 this year; the lunar calendar determines when this weeklong holiday falls, typically in January or February. But that doesn’t really make much sense, says Jianguang Shen, economist at Mizuho—especially since January exports usually benefit from a February Chinese New Year.

The more likely culprit is the surging dollar. The People’s Bank of China links the value of the yuan to the US dollar. As the greenback has grown in value against the euro and yen, so has the yuan—making Chinese goods much more expensive in Europe and Japan, two of its biggest export destinations. Exports to Europe fell 5% in January, after expanding 5% in December. Exports to Japan were even worse—down 21%, versus a drop of only 7.2% the previous month.

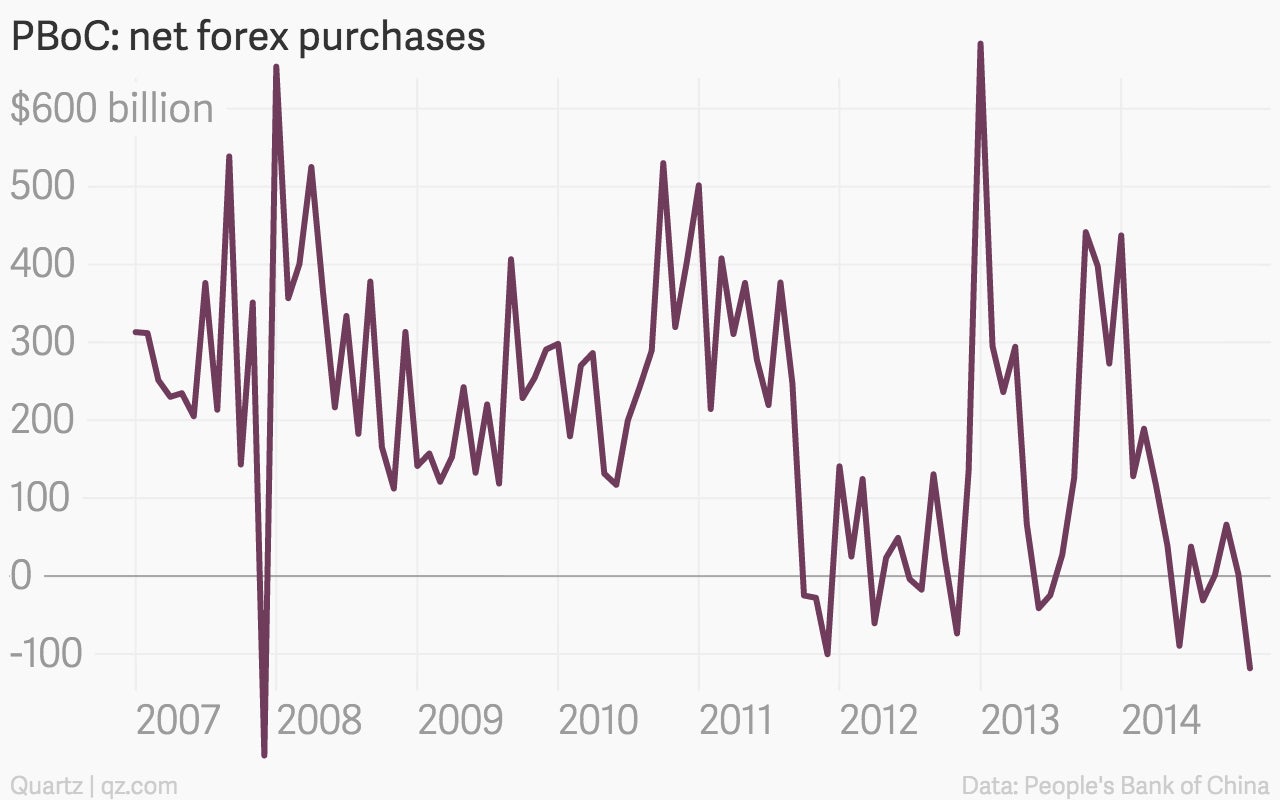

The PBoC can weaken the value of the yuan by buying dollars off exporters. The problem is, if people think the yuan is going to keep shedding value, they’re likely to trade those yuan for dollars—i.e. capital outflow.

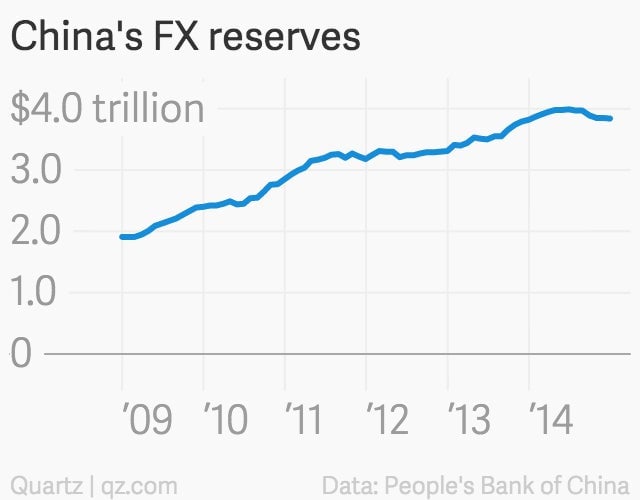

A sudden outflow of capital that will suck liquidity from China’s financial system, making it prone to cash crunches like the notorious June 2013 episode. To keep the outflow from turning into a deluge, the PBoC would have to defend the yuan, selling is foreign-exchange reserves for yuan—a move that also drains cash from the system. The PBoC would then have to print massive amounts of money to keep bans from recalling loans, and that could cause inflation to soar, as Victor Shih, professor at University of California, San Diego, explains in this paper (pdf, p.39).

In fact, the PBoC is clearly sweating the risk of capital outflow more than hurting export competitiveness. It’s been selling dollars from its foreign exchange reserves—meaning it’s been forcing the yuan’s value to rise.

Mizhuo’s Shen said he believes the PBoC kept selling dollars for yuan in January, arresting the currency’s slide. The PBoC’s recent surprise cut to banks’ reserve requirement ratio—a move to offset the liquidity drained suggests that Shen’s right.