The most important moment at the Grammys did not involve Kanye West

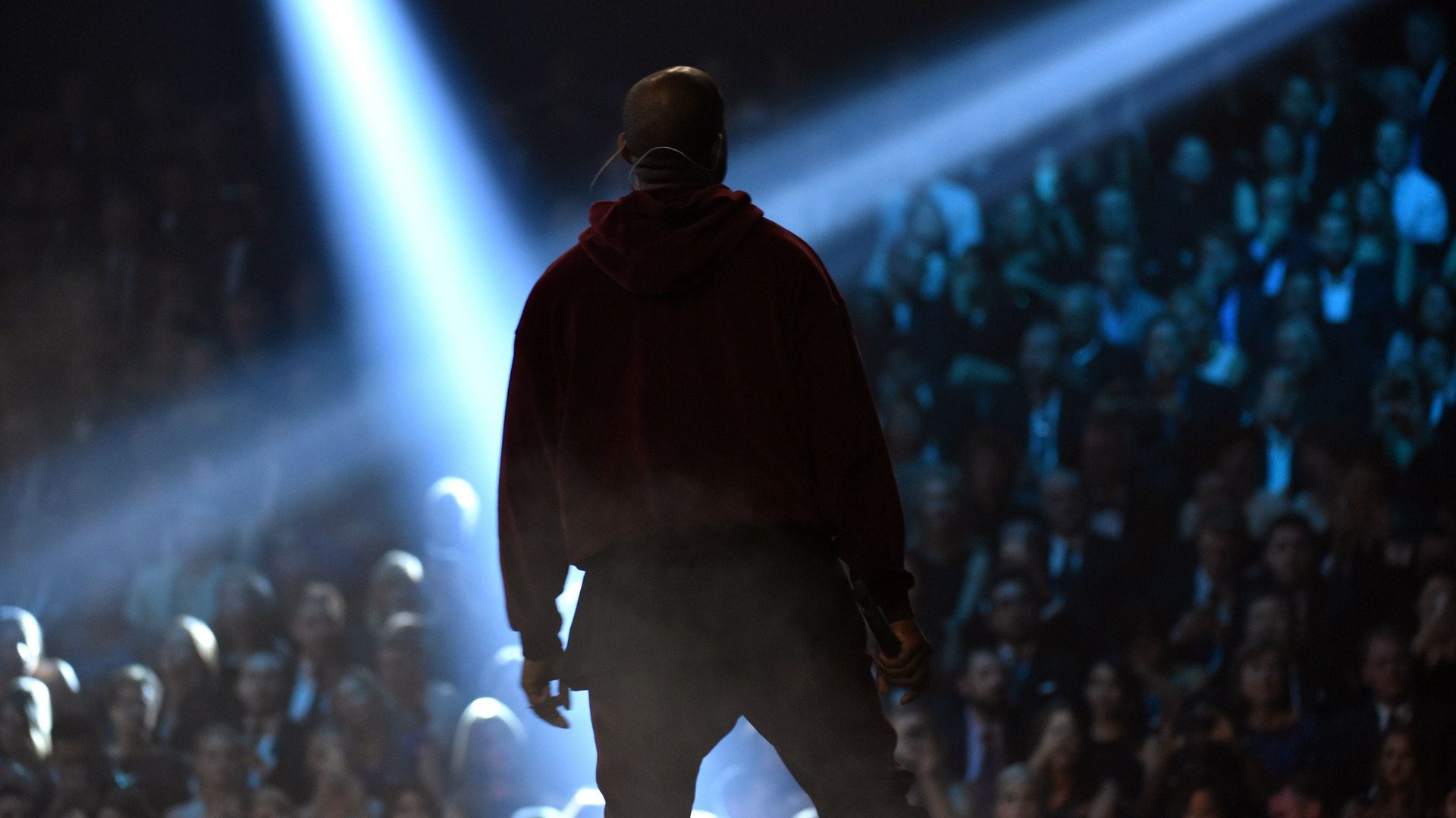

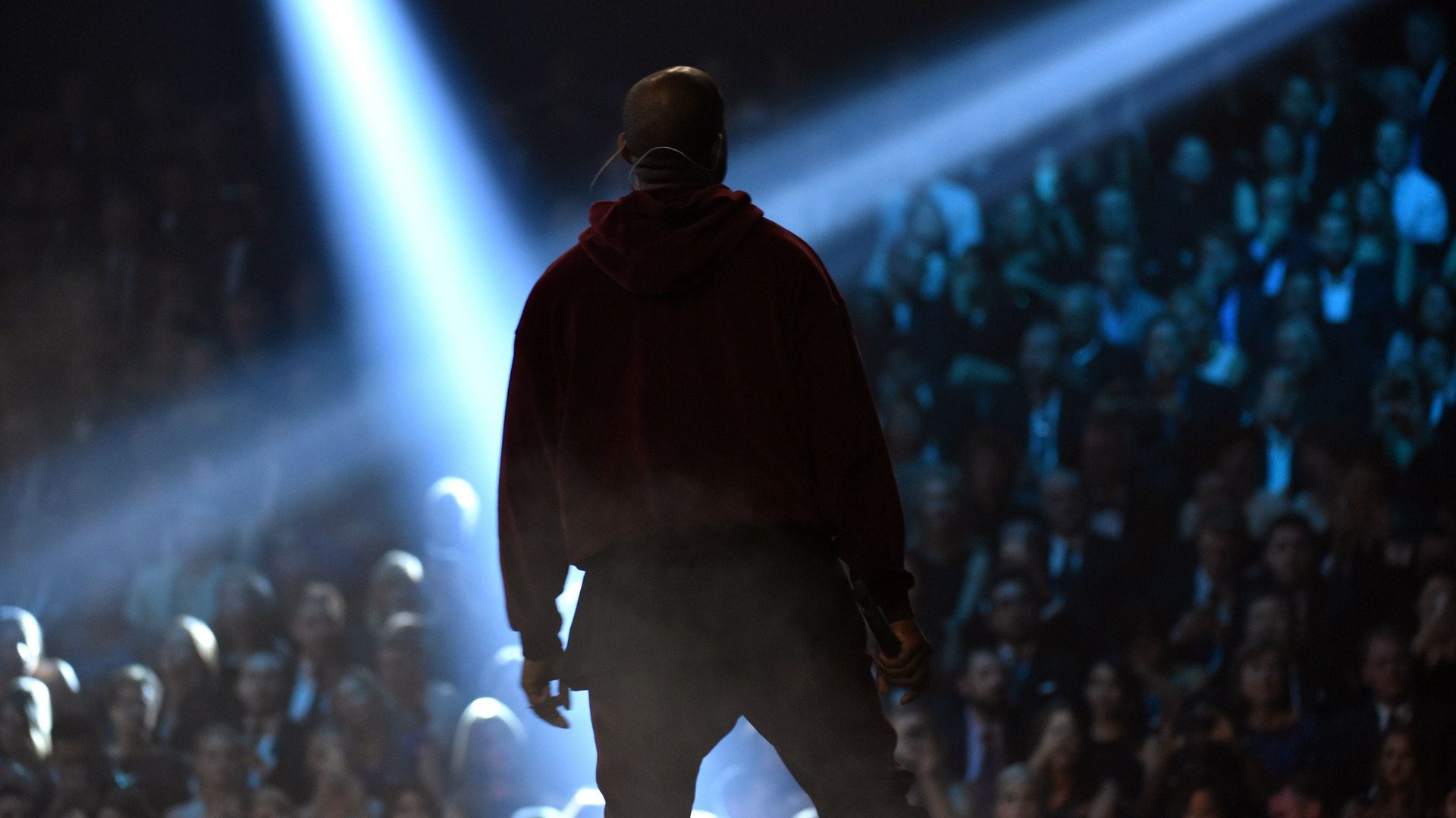

The Grammy awards last night were for the most part underwhelming, except for a brief interruption from the hip hop star once famously described by US President Barack Obama as a “jackass.”

The Grammy awards last night were for the most part underwhelming, except for a brief interruption from the hip hop star once famously described by US President Barack Obama as a “jackass.”

Kanye West, the critically acclaimed rapper who has won multiple Grammys himself, and is married to internet sensation Kim Kardashian, invaded the stage briefly when alt-rock stalwart Beck was announced as the winner of the coveted Album of the Year award. He’s done this before, of course, and the stunt is, not surprisingly, getting a lot of attention today on the internet.

But there was actually a much more important moment last night.

It came when the mind-bendingly complex issue of digital music royalties was briefly thrust into the spotlight.

As Billboard reported, Neil Portnow, president of the Recording Academy, the organization behind the Grammys, announced a new lobbying group that will seek to influence legislation over the amount artists are paid in royalties by new internet-based distribution platforms. “While ways of listening to music evolve, we must remember that music matters in our lives, and that new technology must pay artists fairly,” he said. His comments came as the music industry approaches a key inflection point, and as Washington gears up for a bruising battle over music licensing.

Last year, streaming royalties got a lot of attention when Taylor Swift pulled her entire catalog from Spotify. The skirmish in DC, which Portnow seems to be tacitly referring to, is over a separate but related issue: royalties paid by services that don’t let you choose the specific songs you’re listening to—be that old-fashioned terrestrial radio, satellite providers such as Sirius XM, or webcasters like Pandora Media.

At the moment the system for licensing on these services is a confusing mess. Broadcast radio stations only pay a relatively small percentage of revenues in royalties to songwriters and publishers, and nothing to performers or record labels. Pandora pays roughly half of its revenues to performers and labels, and a much smaller amount to songwriters and publishers. Neither Pandora nor Sirius pays any royalties on songs recorded before 1972.

Last week, the US Copyright Office released a 254-page report proposing sweeping changes to this system. (See this good summary by Vox of its recommendations.)

Pandora, whose stock price is under even more pressure after weak quarterly earnings, probably has the most at stake from potential copyright reform. But there are many interest groups jockeying for advantage and more money, including publishing corporations, record labels, distributors, and music middlemen who have existed for more than a century.

That the issue made an appearance at the Grammys, if only briefly, may be a sign that artists themselves are ready to start speaking up, as the long-awaited reform process picks up.