Most CFOs are embarrassed by their companies’ tax avoidance schemes

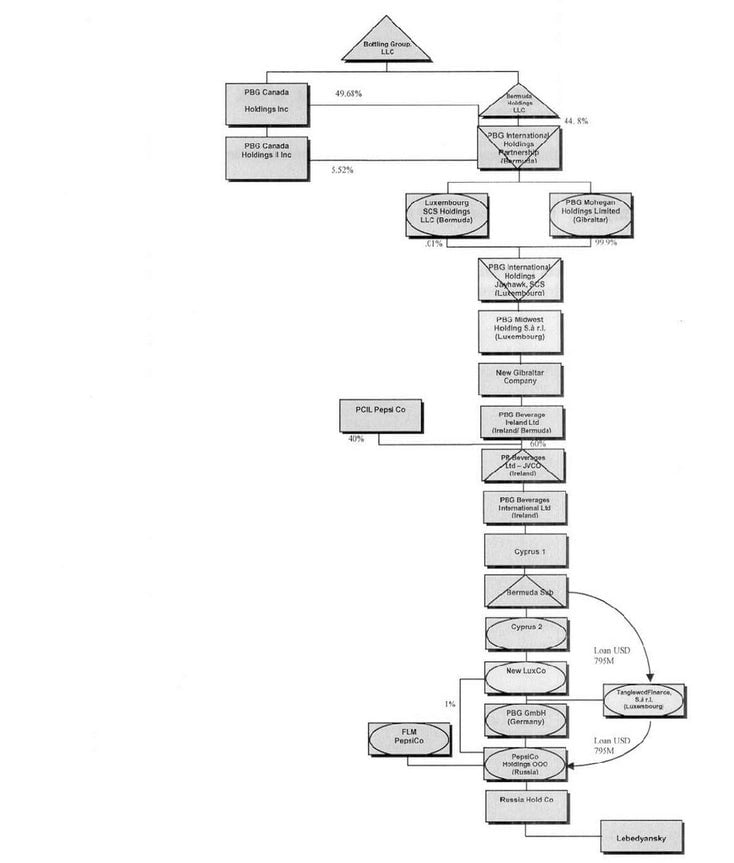

Multinational companies thrive on complexity—just take a look at how Pepsi runs money through Luxembourg shell companies to “optimize” its tax bill:

Multinational companies thrive on complexity—just take a look at how Pepsi runs money through Luxembourg shell companies to “optimize” its tax bill:

Now a new survey by Taxand, a global tax advisory firm, finds that chief financial officers at multinational corporations—the people who oversee these Rube Goldberg creations—aren’t particularly proud of them. More than three-quarters of finance chiefs said that “exposure to the public of corporate tax planning has a detrimental impact on reputation.” That’s some admission—we all know the aphorism that nobody wants to see how sausage is made, but it’s quite something for butchers to say it.

Most of these schemes, however convoluted, are legal. But the plausibility that they are intended for anything other than lowering tax bills has led European officials, among others, to challenge particularly cozy deals where corporations like Apple negotiated special tax deals in Ireland and other countries. Just because something is legal doesn’t make it ethical or popular, and these CFOs are well aware of what happens when customers learn that a large, profitable corporation pays far less in tax than they do.

When its sales started to slip in the UK thanks to bad publicity around its meager tax bill, Starbucks told customers that ”it has become clear that you expect more from us than just to follow the letter of the law.” It promised to pay a base level of tax well above what it could get away with, legally speaking. Still, many—if not most—multinationals would say that the pressures of the public marketplace and competition demand they exploit every possible advantage available to them.

Playing up the shame factor is part of the calculus for corporate tax reform proposals crafted by US lawmakers. President Barack Obama’s most recent compromise proposal attempts to go after these schemes, which have led US corporations to stash $2 trillion offshore, by cutting taxes on overseas income generated by legitimate business activity and blocking attempts to shift US profits offshore, typically by transferring intellectual property to low-tax jurisdictions.

Edward Kleinbard, a tax law expert at the University of South California, says he is confident that anti-abuse rules can stop such profit-shifting, particularly on excess returns on offshore income—like the huge profits companies accrue in the Cayman Islands. But Rebecca Wilkins, head of the non-profit Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency Initiative, worries that even if the minimum tax rate proposed by Obama for foreign income—19%—is applied, the difference between it and the 28% top rate levied in the US will be large enough to keep corporations off all stripes moving profits overseas.

But the US isn’t the only actor in the global economy. “It doesn’t matter what happens to US tax reform, US multinationals are going to pay a great deal more in tax on their foreign income on the future than they pay today,” Kleinbard says, pointing to European crackdowns on stateless income.

That may be why Taxand’s survey reported that two-thirds of CFOs feel “the regular political discussion around potential new tax measures is causing confusion and uncertainty amongst business decision makers.”