Ling Lee, a microbiologist, says it makes sense to think of the nervous system that governs digestion as a brain. The “gut brain,” as Lee calls it, contains hundreds of millions of neurons—“as many nerves as in an adult cat,” she says. And also, it’s autonomous.

If you chopped it out of a body, and gave it a nutrient bath in which to survive, the enteric system, as it’s also known, “would still go chomping through things,” says Lee.

The relationship between the brain and the signal-sending gut is the basis of a whole wing of scientific study. For the next year, some of that research will be collected at London’s Science Museum.

The team that came together for the project, led by Lee, started out by looking at the causes of obesity. But with little public appetite for such a worthy-seeming theme, the group instead zeroed in on a fascinating, fundamental question: What makes us eat?

The answer lies in the relationship between the enteric system, which sends messages of need or satiety, and the brain that receives them. The exhibition featured several examples of this process in action.

One is a living, breathing person: Molly Smith. Because of a medical condition, most of her gut was removed at six months old, after which Smith received all her nutrients via a vein, or sometimes directly to the heart. Taste—pineapple, wasabi, chorizo—was an alien concept for her. Smith ate and drank nothing for almost 16 years. And, lacking an enteric system, she never felt hungry.

Finally, after a multi-organ transplant gave her a new liver, pancreas and small bowel when she was 15, Smith tentatively ate a banana. The slight 24-year-old has since become a “bottomless pit” for food, according to her mother, Ann. Even with a working digestive system, it took a long time for hunger to develop. She only started feeling it in the last six months.

With only a few months’ experience of hunger, she’s not always sure what the feeling is. (She has also struggled with cutlery, having never learned how to use it as a child, the concept of time—with no clear mealtimes as anchors—and chocolate, because of its texture). Her story is told in one of the exhibits and she was on hand at the show’s opening.

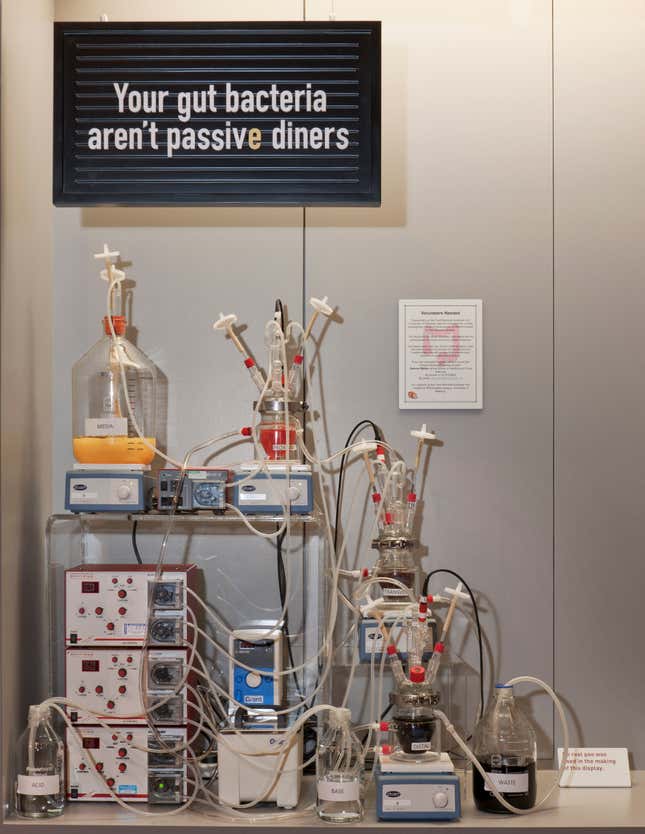

A slew of experiments explore the relationship between the two brains further. Scientists at Imperial College, London, plan to implant a microchip into the gut that can communicate with the brain, tricking it into thinking it’s full. A circuit-board on display (though sadly not being live-demoed) delivers electric impulses to the tongue, and can effectively simulate the taste of lemons.

“Flavor is an illusion that you perceive in your brain from different stimuli,” says Lee, managing to sound both like the medical microbiologist she is, and like some sort of Zen dietician.

There is also much to be learned about how we eat, and how we can control it. Babies “taste” flavours in the womb, one exhibit explains, so pregnant women who eat diverse foods are likely to have less fussy children. Another set of research finds that those who eat a lot of fat and sugar are more likely to have children prone to obesity, and even other addictions, such as alcoholism.

And there’s a reason why, once you’ve given in to the temptation of one piece of cake, you’re likely to do so again.

Researchers from Oregon gave teenagers milkshakes and then scanned their brains. In teenagers who normally ate a lot of ice cream, the milkshakes produced less activity than in those for whom the experience was rare. The conclusion: we crave high-calorie foods naturally—all mammals do, from babyhood—but in satisfying the craving we become used to the effects. Achieving that same brain-firing feeling over time requires richer foods, or more of them.

What’s clear from the exhibit is that an army of researchers is working on how to make the head brain and gut brain work together to make healthier eating choices. But in the meantime, are we getting worse at self-regulating? Lee smiles, and nods: “Definitely.”