The French government thought it had reached a solution to reviving its moribund economy with la loi Macron.

The law—named for Emmanuel Macron, the 37-year-old former Rothschild banker who is now the economy minister—would allow large shops in specially-designated tourist zones in Paris and the French Riviera to open on Sundays until midnight. Shops in other areas would be free to open up to 12 Sundays a year rather than the current five —a major culture shock for the French.

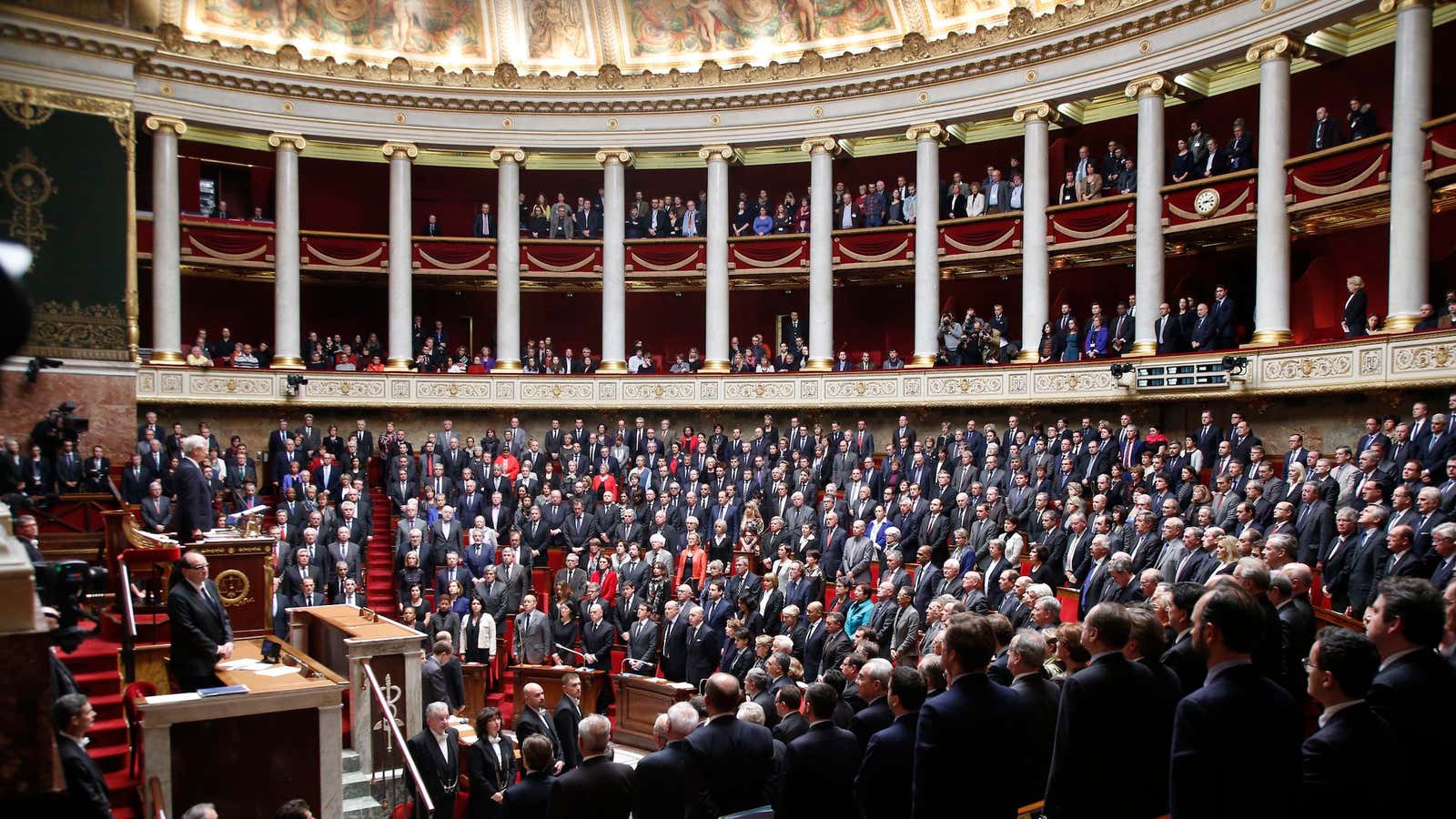

The law has proved much more controversial than expected. Yesterday, rather than “risk the rejection” of the law in the face of a rebellion from his own party, prime minister Manuel Valls instead used an arcane measure in the French constitution to pass the law by decree—without a vote of the National Assembly.

The only way for opponents to defeat the bill is win a vote of no-confidence in the entire government. That vote is scheduled for tomorrow—opponents need an absolute majority of 289 of 577 MPs (link in French) to bring down the government, which is unlikely to happen.

Macron has denied that this is a “coup,” pointing to the 200 hours of parliamentary debate and more than 1,700 amendments (link in French) to the law that the government has accepted to get to this point.

The section of the constitution that allows such dictatorial action, Article 49, is a quirk of the formation of the Fifth Republic in 1958, which imbued the state with the authoritarian leanings of its founder, Charles de Gaulle. Still, Article 49 is a tool that has been used sparingly—only 83 times since 1958 (link in French). In fact, the current president, François Hollande, denounced the practice as recently as 2006 (link in French).

Is such drastic action even worth it for this law? The law leaves the 35-hour work week alone, a major point of contention between Macron and his fellow Socialists in the past. The Sunday opening hours may take the headlines, but there are all sorts of regulations being amended—some more quirky than others. Among other things, the Macron law (link in French) :

- introduces more competition in legal services for jobs such as bailiffs and court clerks;

- opens up inter-city bus routes to allow them to compete with the trains;

- sets rules for selling state assets, which might mean the sale of stakes in airports in Nice and Lyon;

- regulates how long taxis can wait for their customers outside buildings and airports;

- removes the requirement for farmers to employ architects when they make minor changes to their land.

Leftwing deputies in parliament may be outraged but others wonder why the French find it so hard to pass such relatively minor and simple reforms—Germany’s Deutsche Welle said the new law is “no French Revolution” for the country’s economy.

At the very least, Macron has one thing going for him in the battle over reviving the French economy: Six out of 10 people support his reforms (link in French).