Move over, spider silk. There’s something else out there in nature that’s made of even stronger stuff: limpet teeth.

The structure of these tiny sea snails’ choppers is so strong, engineers could copy it to make cars, planes, and other objects prone to collision, says Asa Barber, an engineering professor at the University of Portsmouth who announced the discovery in a just published study. They could also be used to make false teeth for humans.

But that’s probably getting ahead of things—such as the fact that these little snails even have teeth.

To back up a little, the terms “limpet” refers broadly to aquatic snails, and the species Barber examined—Patella vulgata, or the “common limpet”—is an edible variety that abounds on western European shorelines. They grow to 5 cm (2 in.) in diameter, and are thought to live as long as 20 years. Also remarkable is that they clamp themselves to tidal crags with such force that they often leave an oval “scar” in the rock face.

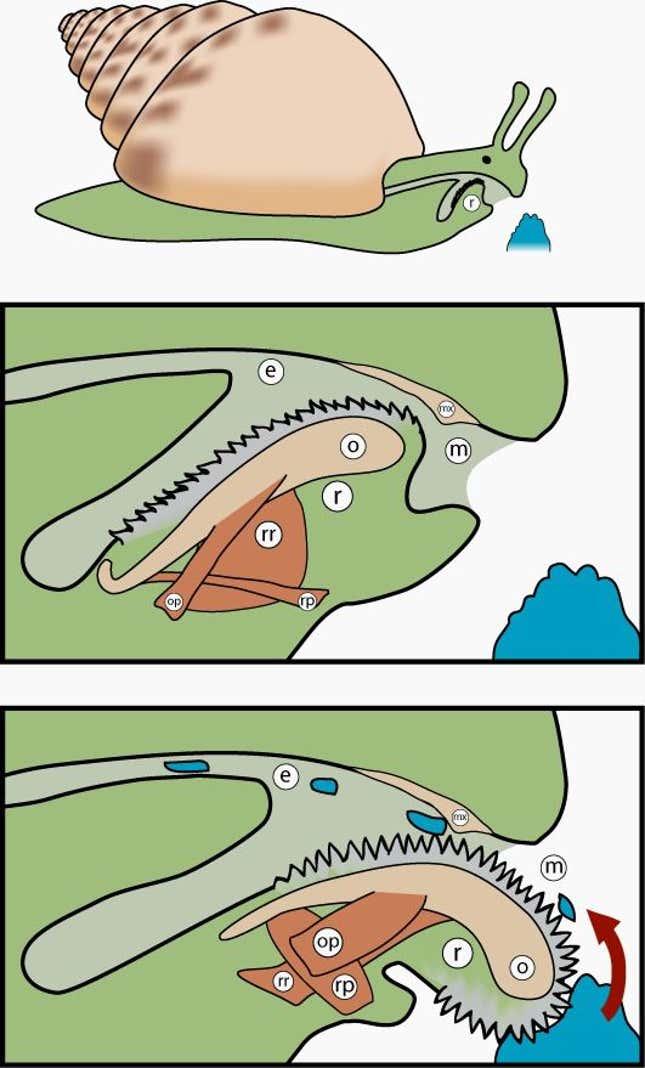

But that’s nothing compared to what their “radula” can do. When limpets get hungry, they stick out this tongue-like structure, which is lined with row after row of wee teeth, and scrape over the rock to loosen algae.

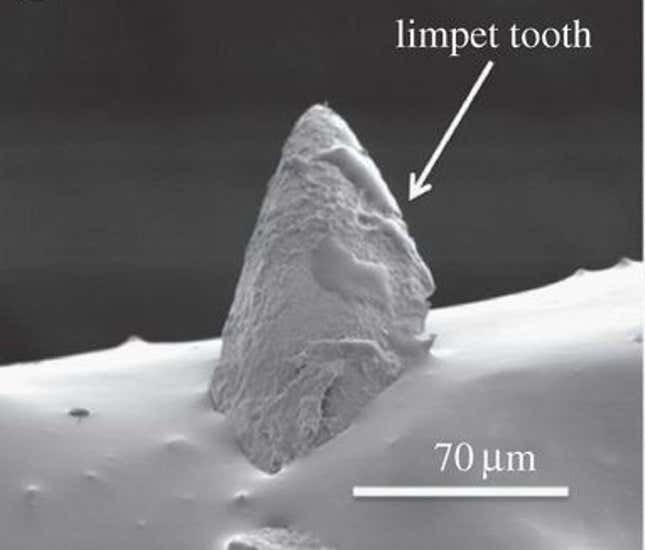

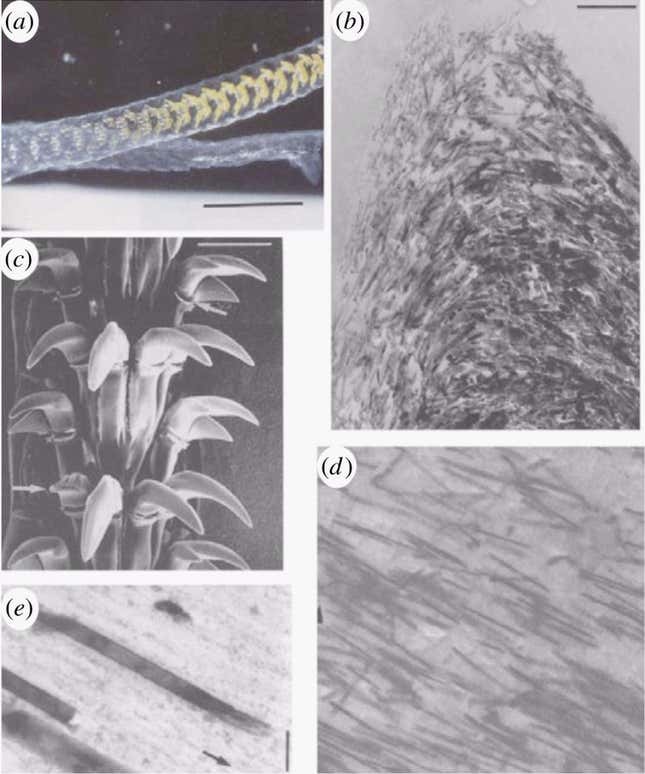

In order not to be worn away by rock, they have to be mighty tough, even if each little limpet fang is less that a millimeter long. They’re obviously pretty hard to break apart: Barber used a a new technique involving atomic force microscopy to yank apart a sliver of toothy material nearly 100 times thinner than the breadth of a human hair. The substance he found is made of what he calls “an almost ideal” mix of protein reinforced by fine mineral nanofibers called goethite—creating a structure so sturdy it outperforms spider silk, which scientists had believed to be the strongest biological material.

The limpet tooth composite could be what’s called “bioinspiration”—a natural biological design that could be copied commercially.

“This discovery means that the fibrous structures found in limpet teeth could be mimicked and used in high-performance engineering applications such as Formula 1 racing cars, the hulls of boats and aircraft structures,” says Barber.

Top image by Flickr user Tim Green (image has been cropped).