South Africa’s ruling party has had a rough week.

The African National Congress, which led the country’s transition to majority rule, finds itself under fire following a row in parliament that erupted after Speaker Baleka Mbete, who doubles as ANC chairperson, ordered the removal of legislators seeking to question President Jacob Zuma during his annual address to the nation.

The ANC later admitted to jamming cellphone networks and enlisting national police to quell the legislators, including Julius Malema, who leads the Economic Freedom Fighters, an upstart political party that won 25 seats in last year’s election.

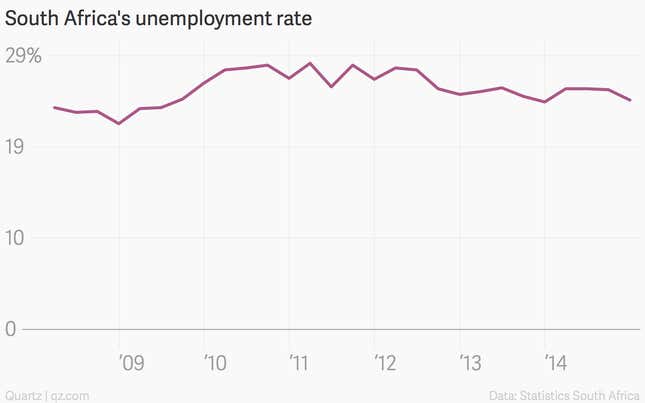

In his speech, Zuma touted the government’s push to create “job opportunities,” spur private investment, and remedy a shortage of electricity that has left many South Africans in the dark. Mmusi Maimane, parliamentary leader of the opposition Democratic Alliance, called Zuma’s remarks “the words of a broken man, presiding over a broken society.”

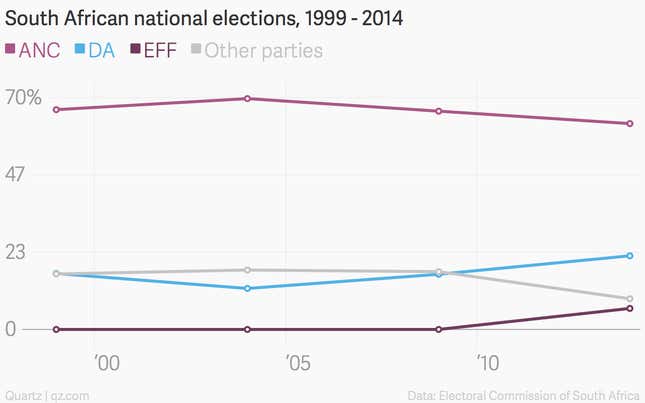

The dustup presages the ANC’s shrinking majority and underscores the vibrancy of South Africa’s democracy, for better and worse, observers say.

Maimane’s speech “captured people’s imagination in a way that hasn’t happened in a long while,” Adam Habib, vice-chancellor and professor of political science at the University of Witwatersrand, tells Quartz.

“I didn’t like the attempt at jamming, and the violation of procedure, but I think it’s a reflection of the strength of the democracy that we can have a robust engagement in the parliament itself,” he adds.

For his part, Malema accused Zuma of contravening the country’s Freedom Charter, which holds that South Africa belongs to all who live in it. “Malema has really captured many people’s imaginations,” says Jonny Steinberg, a journalist and professor at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research. “One of the reasons he did is that he is asking genuine and substantive questions about what this democracy is and what it means to be free.”

Still, Steinberg says he “would like to think that both [the ANC and EFF] came off pretty badly among the electorate.”

To some extent, the dispute crystalizes frustration with Zuma’s leadership that parallels a dearth of economic opportunity. South Africa’s economy is forecast to grow 1.6% this year, according to HSBC, which recently lowered its estimate, citing the energy crisis. A quarter of South Africans say the government must root out corruption, more than double the percentage from a decade earlier, Afrobarometer finds.

The ANC is likely to be tested again next year, when a split of the National Union of Metalworkers from the country’s main labor federation threatens to siphon support from the party in local elections.

Whether opposition parties can capitalize on the ANC’s woes will depend on whether they can broaden their appeal. The EFF has demonstrated its ability to win votes in urban townships, but its call to nationalize industries and redistribute land may limit its ability to cross political boundaries.

Though the DA garnered 22.2% of the vote last year, up from 16.6% five years earlier, the party has struggled to gain ground in the poorest communities. The test for Maimane will be whether he can steer the DA “to become responsive to the inequality divide in our society,” says Habib.

That leaves the ANC and Zuma, who will continue to face questions about his residence and the economy. Or, as Habib wonders, “does the party…recognize that he’s an albatross and take actions?”