Ocean acidification—it’s happening, and US coastal communities should start preparing now, especially if the rest of us want scallops, oysters and other shellfish to keep appearing on our restaurant menus and dinner plates.

That’s the message of a new study that shows that America’s shellfisheries are more vulnerable to this less considered counterpart of climate change than previously thought. That vulnerability is due to more than changing ocean chemistry. Social and economic factors, in addition to pollution and natural ocean processes, are conspiring to make ocean acidification a problem sooner rather than later.

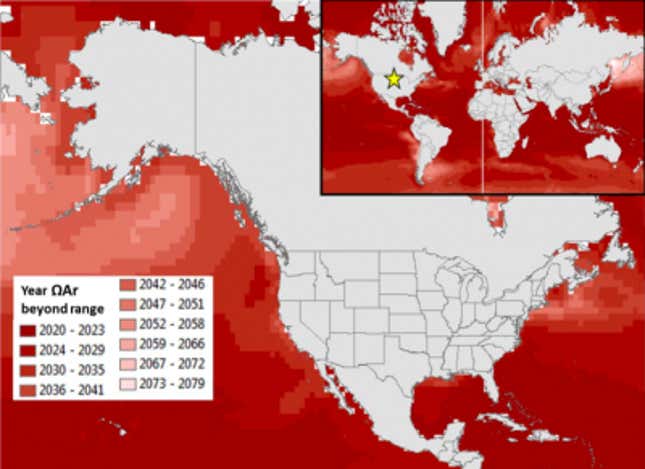

The chemical process of ocean acidification starts with the extra carbon dioxide humans are adding to the air—through vehicle exhaust, agribusiness, and other variables. About 25% of it is sucked up by the ocean, where it dissolves and contributes to making the ocean more acidic, and subsequently less friendly to carbonate—a compound that shellfish and coral need to grow.

But this new study, published in Nature Climate Change on Monday, makes it clear that while ocean acidification may make conditions tougher on shellfish, how much coastal communities rely on those shellfish and how ready they are to deal with changes makes a big difference in how ocean acidification plays out on land. With more than $1 billion in revenue going to US coastal communities from mollusk-fishing, on which the study focuses, just how prepared those communities are could have huge financial ramifications nationwide.

“The conventional wisdom has been to think of vulnerability to ocean acidification only in terms of ocean chemistry. We wanted to fold in a few other dimensions, particularly socioeconomic dimensions, to fill out that picture,” says Lisa Suatoni, a senior scientist for Natural Resources Defense Council who contributed to the new study. “Doing that, you see many more communities are vulnerable to ocean acidification than previously thought.”

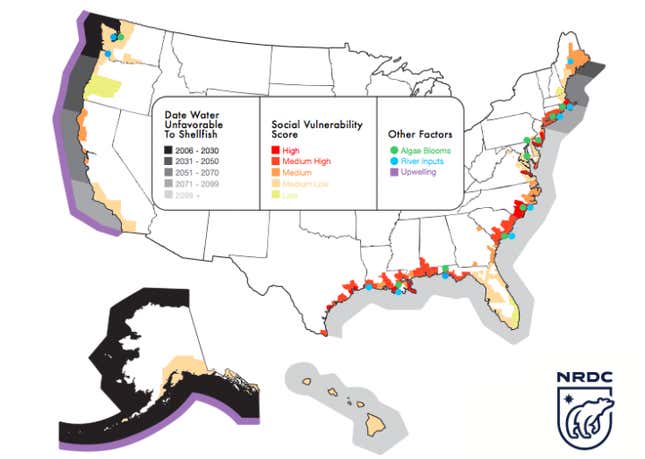

Of the 23 coastal regions in the US identified by Suatoni and her colleagues, 16 will face ocean acidification levels unfavorable to shellfish populations. Overlaying social factors, levels of agricultural runoff, local pollution, and upwelling (a natural ocean process that brings more corrosive deep ocean water to the surface) help tease out regional differences in vulnerability.

In the Pacific Northwest, vulnerability lies at the lower end of the spectrum, despite high acidification rates coupled with heavy runoff and upwelling. Suatoni says this reflects strong policies already in place, regionally, because ocean acidification contributed to an oyster hatchery crisis that hit the region about 10 years ago. By 2008, harvests at one local hatchery declined by about 80% because acidic waters and a lack of carbonate essentially made it impossible for baby oysters to form their shells.

“They only have two days to build that shell. If they don’t build their shell, they starve,” Suatoni said.

In response to the issue, which threatened the region’s $111 million industry, scientists, state governments, and hatchery owners implemented an early-warning system that gives hatcheries a heads up when a wave of more acidic water is headed their way. That allows them to close intake valves, or treat the water to ensure there’s enough carbonate for oysters to survive.

On the other side of country, fisheries in Massachusetts face lower acidification rates, but higher vulnerability. Southern Massachusetts brings in more than $300 million in mollusks annually, accounting for the vast majority of the region’s fishing revenue.

“Massachusetts and Maine are places that are just screaming for problems,” Suatoni says. “New Bedford, is the highest earning fishing port in the country. Eighty-five percent of landings are coming from one species: scallops. They’re really vulnerable.”

Even areas with low acidification rates, such as the Gulf Coast are still highly vulnerable because of un-diverse economies and harmful algae blooms that can exacerbate the impacts of acidification. By identifying those vulnerabilities now, New Bedford and other similarly positioned ports can consider what steps they need to take to address inevitable acidification crises before they hit.

“Developing these types of studies, that bring the results into a greater community context, is extremely valuable to policymakers that need to make decisions for their areas,” says Jeremy Mathis, director of ocean and environmental research at the Pacific Marine Environmental Lab.

“Now is the time to start planning. We don’t want to wait until there is a disruption. These documents provide that incentive for communities to start developing adaptation strategies now that will hopefully provide for them in the future.”

A version of this post originally appeared at Climate Central.