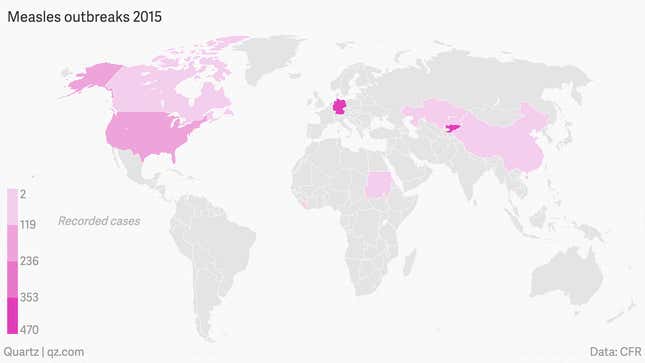

This week, a toddler died of measles in Germany, the first victim of an epidemic that has infected 570 people since October. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, since the beginning of 2015 there have been 1,330 registered cases of measles—one of the most contagious known diseases—in Asia (540), Europe (468), North America (227), and Africa (95).

These outbreaks are happening primarily in areas with lower levels of immunization of children. Liberia has a 74% immunization rate, Sudan 85%, while Germany has 97%, Canada 95% and the US 91%.

Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and China reportedly have a 99% immunization rate according to both WHO and World Bank. Yet this rate only applies to the youngest cohorts; unvaccinated older children and pockets of lower vaccination rates in rural areas or amongst certain minorities (for instance, nomads) still cause outbreaks in these countrries.

The problem in Liberia and Sudan is the low immunization rate—although available, the measles vaccine is not easily accessible for at least 90% of the population, which is the minimum recommended rate necessary to reach herd immunity for measles.

In Germany the origin of the the current outbreak is believed to be an asylum-seeking child from Bosnia. The contagion has been possible because the adult population over-45 doesn’t have high rates of immunization, and many younger adults have not had the second vaccine dose which has been recommended since the late 1990s.

On the other hand, the recent outbreak in the US, started at a Disney amusement park in Southern California and spread through 17 states as well as Quebec, and has affected over 150 patients, mainly children who had not been vaccinated.

This has exposed what appears to be a proper first world problem (and American, particularly): parents who refuse to vaccinate their children, or anti-vaxxers, 15 years after measles has all but vanished.

One reason for the rise of anti-vaxxers may be the consequence of the success of inoculation campaigns. Vaccines have worked well in the US, and so Americans haven’t been reminded how dreadful measles can be in quite some time, and so they are more likely to fear the consequence of the vaccine than appreciate what it protects their kids against.

Orin Levine, director of vaccine delivery at the Gates Foundation, told Quartz that in the countries where the risk of contracting an infectious disease such as measles, “there are grim reminders of the importance of vaccine preventable diseases every single day. The threat of measles is not abstract, it is tangible.”

Parents, he says, go to great lengths to ensure their kids are vaccinated, because they know how scary the diseases can be:

“Just about a year ago, I was in Northern Nigeria, near Kano, and went to visit a rural health center. One woman had a 17-month-old baby who weighed about nine-and-a-half pounds. This is a kid who was severely malnourished, exactly the kind of kid that measles robs the life from. She had walked past her local health center to this health center, specifically because she knew that measles vaccine was there and was adamant, ‘I’m not leaving this place today until my kid gets vaccinated against measles.'”

Indeed, it appears that even one reminder is enough to get a clear sense the importance of measles vaccination: immediately after the death of the toddler in Germany, the German health minister said he might promote the enforcement of mandatory immunization campaigns.