China’s corruption crackdown is making an attempt at pulling on the heartstrings. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) has started publishing emotional confessions of corrupt officials in a special column on its website: “the confession diary.”

The splashy interactives feature video clips, photos of remorseful officials in jail overlaid with quotes from their confessions, and details of their cases. By publicizing cases of typical disciplinary violations, the government hopes to give cadres a “wake up call.”

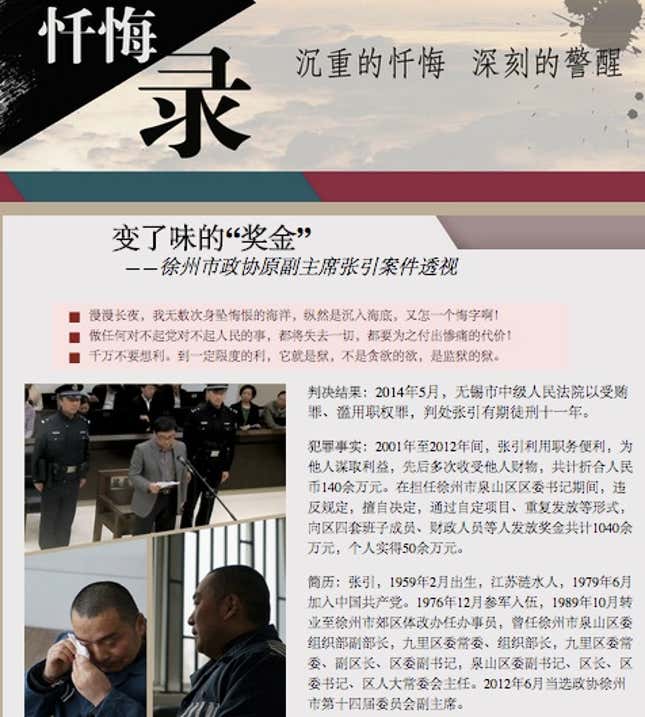

“Behind every corruption case lies the shadow of a lost model of power, behind every book of repentance hides the remorse of self-blame and self-hate,” CCDI posted on its website on Feb. 25, announcing column, which looks like this:

Zhang Yin, the former vice chair of the CPCC in Xuzhou city in Jiangsu province, was the first to be featured. The 56-year-old was caught accepting bribes and has been sentenced to 11 years in prison. In a video on the site, Zhang mentions his 85-year-old mother who is waiting for the day he leaves prison: ”I am unworthy of my mother, this organization, and society. If I could do it all again I would rather give up my life than abuse the law. I hope other cadres will use me as a warning and that other corrupt officials can learn from my mistakes.”

As Chinese president Xi Jinping’s corruption crackdown continues, these confessions are becoming more routine. A prosecutor with 10 years of experience told a Chinese newspaper in Guangzhou in January that the standard confession by a Chinese official involves a lot of crying and sometimes kneeling in front of prosecutors to show remorse.

Notable confessions include one from Liu Tienen, the former deputy of China’s planning commission, the National Development and Reform Commission. Liu admitted in 2013 to taking bribes of up to $35.6 million yuan ($5.8 million), telling prosecutors, “I’m so sorry that I worked more than 30 years at the NDRC, with the trust of the leaders and my comrades, and smeared a black mark on my workplace…I am completely and bitterly remorseful.”

The dark side of this corruption soap opera is the suspicion that many of these confessions are coerced. In December, Chinese state media admitted that it is not rare for the police “to extort confessions through torture,” when an 18-year-old convicted of murder was declared innocent nearly two decades after he had been executed. Chinese officials are also subject to an opaque extra-judicial disciplinary system operated by the Chinese communist party called shuanggui, in which torture and mysterious deaths are not unusual.