There could be as many as 150,000 drone jobs in Europe by the year 2050, says a report out today from the EU Committee of Britain’s House of Lords. Those jobs include piloting as well as manufacturing and other support work. In the US, the drone industry has claimed there’ll be a similar bonanza. But there are a couple of catches.

First, people need to know how to fly them. In the UK, commercial drone pilots need a form of aviation license, and regulations ban them from being flown over built-up areas or crowds, or out of sight of the pilot. But the aviation industry is still worried. It has said that “leisure” users might at some point cause “a catastrophic accident,” which could damage the growth of the industry, the report says.

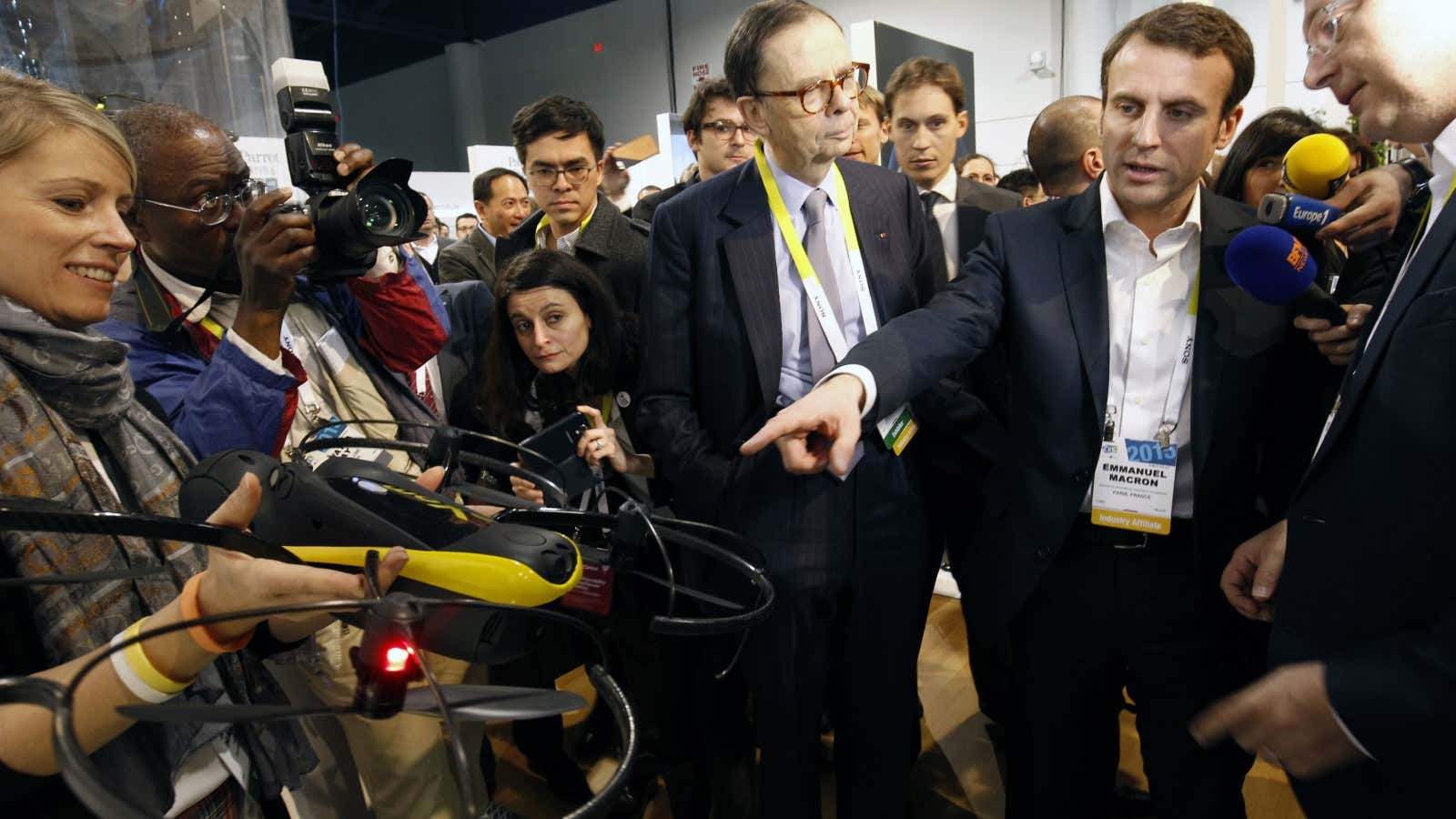

Then, there’s the problem of public perception. Drones clearly make people nervous, even though there’s a world of difference between the small commercial devices and the massive military drones that patrol the skies over war zones. The unexplained sighting of drones above Paris last week had a city that had recently experienced a terrorist atrocity immediately on edge.

While small drones are already increasingly used for filming and photography by journalists and movie-makers as well as enthusiasts, they also have less visible uses: farmers surveying their fields to plan crop rotation, estate agents taking aerial shots of houses, and infrastructure companies checking on cables and or bridges. All of these make privacy a particularly fraught issue. To deal with that, the report calls for pilots to be made aware of rules that protect ordinary people from having their private lives inspected or their data collected.

Keeping track of what drones are in the sky should help. The report also recommends creating an online database on which drone operators would share their flight plans, and suggests that the UK and Europe team up with NASA. The US space agency already researching the development of such a system, which might eventually function as a kind of drone air-traffic control.