The French author Georges Perec earned peculiar literary distinction by writing a 300-page novel called La Disparition (A Void) without once using the letter “e.” His countryman, Michel Dansel, published Le Train de Nulle Part (The Train from Nowhere), a novel in which he managed to avoid the use of a single verb. I envy these writers, whose lives were apparently so graced with calm that the only thing they want to exclude from their thoughts was a letter of the alphabet or a part of speech.

I live a less blessed life. As an Israeli and a journalist, my aspirations are more limited, yet less within my own power to achieve. I aspire to be able to write about my country’s politics without using the name of the current prime minister. I’d like to write my next 300 articles without the N-word. I’d like to think of him, if I think of him at all, as a vague faceless historical memory like, say, James Buchanan.

Israeli elections are about a week away. There should be reason to hope. Exhaustion with the prime minister, with his voice, with his confusion between the state and himself is widespread. Each day’s news brings new scandals. He is the issue of this next national election—his relations with the Obama administration, his record devoid of achievements, his extravagant expenses billed to the taxpayers. ”It’s him or us,” is the election slogan of the left-of-center alliance called the Zionist Camp, headed by Labor leader Isaac Herzog and indefatigable peace advocate Tzipi Livni.

And yet, I’ve come to realize that the focus on him is a strategic success for the prime minister’s election campaign. It distracts voters’ attention from minor questions such as the Palestinians, peace, housing prices, and poverty. It allows him to set the agenda as, “It’s me or them,” while defining “them” as anti-Zionist elitists who are allies of Iran, the so-called Islamic State and, heaven help us, Barack Obama.

The conviction of people like me—who think peace is possible, who question the war last summer in Gaza, who support the rights of African refugees in Israel—that he must go only increases his support among Israel’s Orthogonians. “Orthogonians,” you may recall, is historian Rick Perlstein’s term in his book Nixonland for the anxious majority of Americans who experienced the 1960s as an assault by stuck-up elites on patriotism, decency, and the social order. Orthogonians put Richard Nixon in the White House. Like Nixon, Israel’s incumbent prime minister is a maestro of resentment.

Take the Israel Prize affair, the country’s highest civilian honor. The experts who choose the annual winners are appointed by the Education Ministry. The education minister has to sign off on the appointments, but that’s been a formality—until this year. During the political crisis that sparked early elections, the prime minister fired a large part of his cabinet ministers and became their caretaker replacement. As a result, he had to ratify the choice of this year’s prize committees—and he quietly proceeded to veto judges for the literature and film awards. It’s no coincidence that the leading candidate for literature prize this year was novelist David Grossman, an eloquent critic of current and past national leaders, and that Israeli cinema has become the art form of national conscience. He wanted to stop honoring critics.

When news broke of the prime minister’s covert intervention, other judges resigned and candidates, including Grossman, withdrew. A legal ruling that the prime minister had exceeded his pre-election caretaker role forced him to back down. Between the legal defeat and the media denunciations of his attempt at culture-control, you might think that the affair was a nightmare for someone seeking reelection. The prime minister knew better; he knew that the fury came from people who never would have voted for him anyway. On his Facebook page, he announced that once re-elected, he’d make sure that “anti-Zionist” and “extremist elements” wouldn’t serve as judges and honor members of “their clique.”

Words like “clique” are basic to his rhetoric. They signal that he’s on the side of the authentic, patriotic, decent, disrespected, excluded people. The prime minister’s personal resentments begin with his historian father’s failure to get a university position in Israel, which father and son blamed on leftist domination of academe. The core resentment of many of his voters, actually more justified, is that Jews of European ancestry dominate the economy and the arts, excluding those with Middle Eastern roots. Even though the prime minister is himself part of the Ashkenazi (European) elite, their anger at exclusion resonates with his. After years in power, he still manages to run as the outsider.

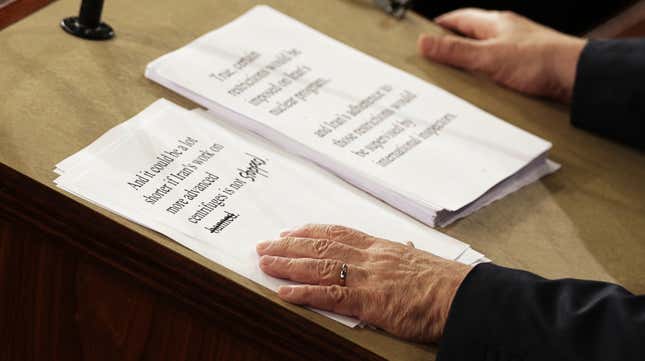

Then there’s his speech to the U.S. Congress. Prima facie, it was a blunder, intended to show him in the role of statesman on live broadcasts two weeks before the election, and instead causing a crisis in relations with Israel’s one reliable ally. Yet he refused to back down. It’s his sacred duty, he says, to warn in every possible forum that an accord will allow Iran to keep developing nuclear weapons “for the goal of our destruction.”

In the latest stage of the rift, the Obama administration has reduced the amount of information on the current negotiations with Iran that it shares with the prime minister. Iran hawks in Israel say the prime minister has made a bad agreement with Tehran more likely. But those are rational objections. He is appealing to the deepest post-traumatic fear of his voters: The world, including the West, is always ready to abandon the Jews. The speech shows that we won’t go easily. It’s the diplomatic version of the Masada myth: defiance even when the situation is hopeless.

Even the scandals, I fear, play into his hands. First it emerged that the prime minister’s wife had ordered employees at his official residence to give her the deposits on returned bottles that had been bought with state funds—a kind of theft so petty as to be incomprehensible. Last week, the state comptroller released a report on extravagant spending at state expense by the prime minister and his spouse, some of it possibly involving fraud. They’d used a straw company, for instance, to hire a Likud hack to do “emergency” electrical repairs at his house on Sabbaths and Yom Kippur, with the “emergencies” occurring weekend after weekend. The former manager of the prime minister’s residence, granted immunity, spent a whole night talking to police investigators last week.

It should be relevant that the prime minister believes that “L’état c’est moi“— “the state is me,” as Louis XIV supposedly said—not to mention that he may have used his office to pay off a small-time crony. But when the top headlines on a news site are about the electrician, they are not about bigger issues. Some of the prime minister’s voters will see the media and police investigations as politically motivated persecution. Others will credit the allegations, but still prefer to vote for the crook rather than for people they believe are too soft on Iran and Islamic terrorism. Were the situation reversed, leftists would do the same. I hate to say this aloud, but integrity is an issue for people who feel physically and economically safe.

Could Israelis possibly re-elect this catastrophic man? I don’t know. Americans re-elected Nixon and George W. Bush. Israelis aren’t crazier than Americans but I don’t have reason to believe that they are cleverer.

I could be wrong. I pray I’m wrong. The polls showing that the parties of the right will win a majority could be off target; Israeli polls usually are. This is a country of volatile mood shifts. On Election Day, disgust with him could sway enough votes to change everything. Maybe the N-name will fade at last from my sentences, from the political vocabulary of a bruised nation.

Follow Gershom on Twitter at @GershomG. This post was originally published on The American Prospect.