A recent study published in Evolution & Human Behavior has confirmed what Kim Kardashian’s #breaktheinternet phenomenon already suggested: men like women with curvy bottoms. In fact, the study suggests, they have liked them since prehistoric time, when there was very good reason to do so. The structure of the female hominid made her posture subject to a forward shift during pregnancies, so her spine ”evolved morphology to deal with this adaptive challenge: wedging in the third-to-last lumbar vertebra.” Essentially, a certain curve of the lower back would enable “ancestral women to better support, provide for, and carry out multiple pregnancies.”

Two separate tests were conducted with two groups of 100 and 200 men who were asked to rate the attractiveness of a group of women with different buttock size and curvature. The conclusion was that men preferred women with optimum curvature, or 45.5 degrees, notes the study. It’s the shape, then, and not just the size.

According to University of Texas Austin alumnus and Bilkent University psychologist David Lewisthe, who authored the study:

“This adds to a growing body of evidence that beauty is not entirely arbitrary, or ‘in the eyes of the beholder’ as many in mainstream social science believed, but rather has a coherent adaptive logic.”

Just what women need: a scientific, evolutionary justification for a preferred body type.

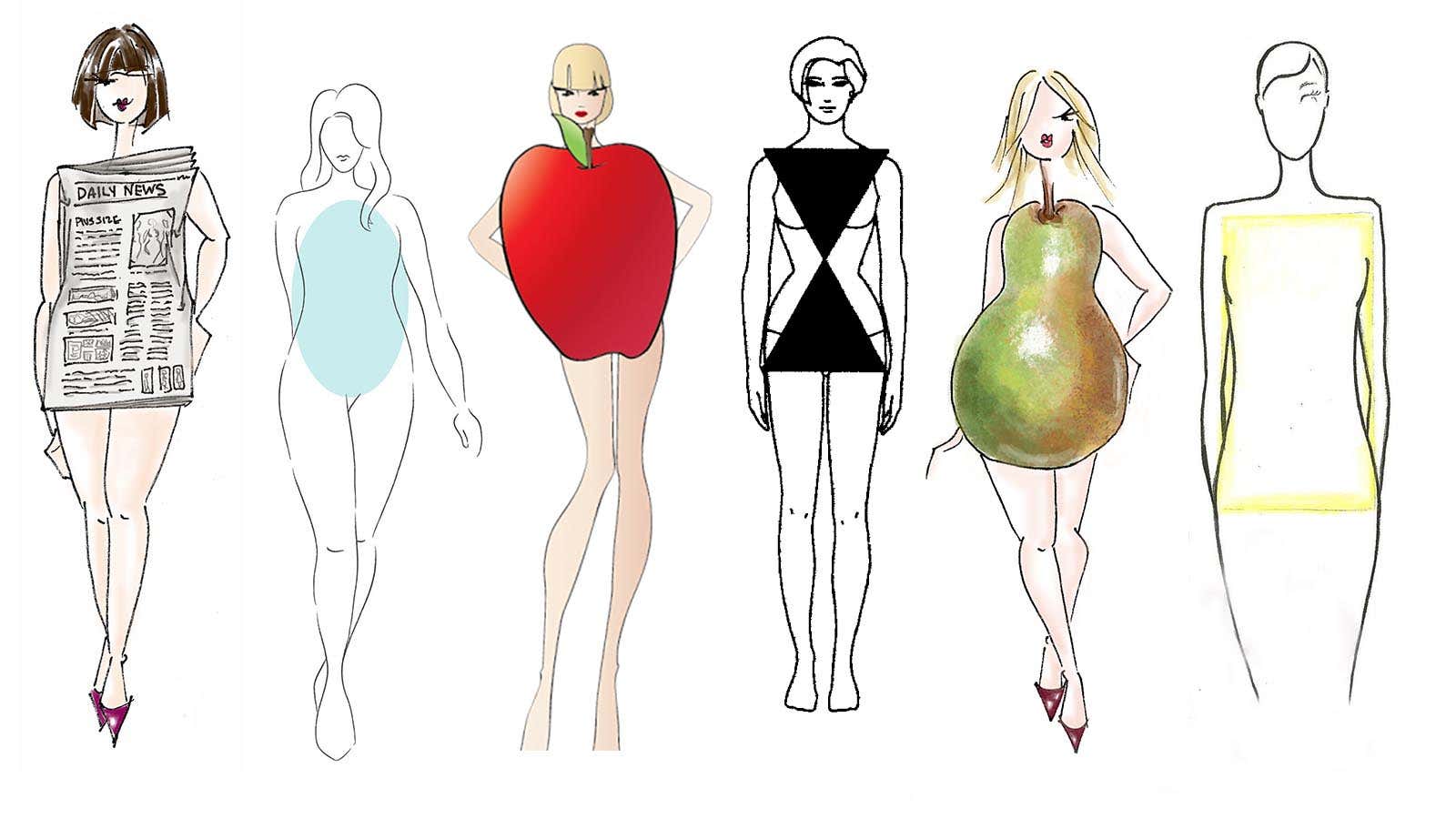

Categorizing women’s body shapes isn’t always so scientific; thumb through a woman’s magazine or clothing catalogue and you’ll often find an illustrated guide that compares body shapes to fruits, vegetables, objects, and geometrical shapes. What’s meant as a “dressing guide” usually serves to reinforce the notion that some shapes are more desirable than others.

A 2005 North Carolina State University study aimed at developing a “female figure identification technique” (FFIT) for apparel provides a good summary of the attempt to diagram women’s body structure:

These categories aren’t definitive; there is, for instance, a Bottom Hourglass and a Top Hourglass, as well as a True Hourglass.

Northwestern University professor Renee Engeln, who studies objectification theory, told Quartz that “researchers generally use the term objectification to capture the psychological experience of having one’s body treated like or turned into an object for others to evaluate. This type of objectification tends to increase body shame, which is linked with depression and eating disordered behaviors.”

There is scientific merit to the study of the human body and its shape, like understanding how fat storage is linked to disease—and in scientific studies the object-like terminology above is used, Engeln says, as “shorthand” for more unusual scientific words (i.e. the technical term for pear-shaped is “gynoid”). However , it appears that the broadest application of body type analysis has one primary function: guiding women into hiding or correcting their bodies. From the best workout for a pear-shaped body to how to dress an apple-shaped one, fitness, nutrition and fashion have been making the most of the knowledge we have accumulated on women’s body types—by employing it to point out what needs to be changed. Engeln says: “The issue is that everyone’s idea of what it means to look good is formed by a culture where the beauty ideal is ridiculously out of reach for almost every woman.”

Broaden the top, thin down the bottom, a little nip here, a tuck there.

As Kate Fox observed in 1997 in her research for the Social Issues Research Center:

Research confirms what most of us already know: that the main focus of dissatisfaction for most women looking in the mirror is the size and shape of their bodies, particularly their hips, waists and thighs.

Perhaps it’s time for researchers to divert their gaze to the male body. A search on Google Scholar produces 1,420 article containing “female body shape,” while “male body shape” is only quoted in 360 articles. Equally, even a general Google search for “female body shape” brings up more results (244,000) than “male body shape” (59,000). This lack of interest for the male body—with the exception for the much investigated penis size—is perhaps the reason why while Wikipedia has a detailed entry for “Female Body Shape,” it directs searches for “male body shape” to “body shape” (same for “human body shape,” to confirm the suspect that a man is a human but a woman is a woman).