“There was a time when you could not be poor enough, or rural enough, to want to live in a bamboo house,” says Ibuku founder Elora Hardy.

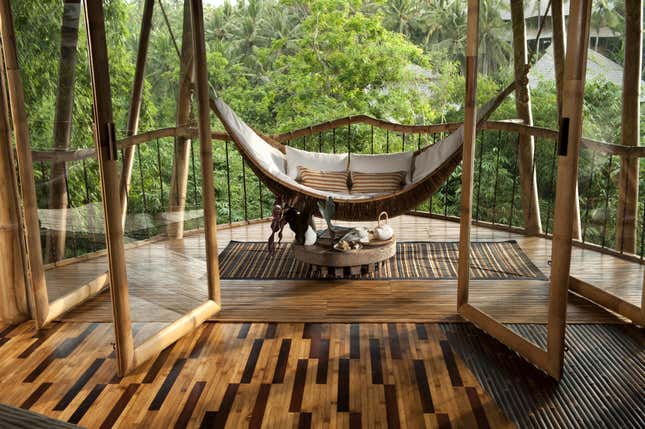

A former print designer for Donna Karan, Hardy now leads an Indonesian firm that creates innovative, luxurious structures out of cheap, sustainable, plentiful bamboo. In a talk at the TED conference last week, Hardy wowed the audience with spectacular images that defy traditional notions of house shapes and construction.

With efficacious insect-resistant treatment, Hardy argues that bamboo is the ideal building material. She explained that it has the compressive force of concrete and the tensile strength of steel, is earth-quake resistant, and light enough to be easily transportable. “It’s hollow, so it can be carried by a small team of men, or apparently one woman,” she said smiling, as she flashed an image of woman carrying poles in a construction site.

Bamboo is also a sustainable and renewable alternative to timber, which makes it a viable way to give denuded forests a break. And it is spectacularly fast-growing. Hardy claims that she has witnessed bamboo, which is actually a kind of wild grass — grow 1 meter (3.2 feet) in one week. Some species grown up to 2 inches an hour, or up to 1.5 meters each day.

Bamboo architecture has actually been extant since the 16th century in tropical areas of the world, and is an emerging architectural and interior design specialty in Asia. But until recent breakthroughs in insecticide treatment, bamboo buildings were considered temporary structures, because bugs and termites would eventually destroy them. “Untreated bamboo gets eaten to dust,” explained Hardy. Ibuku’s bamboo is treated with boron, in a low-toxicity solution that renders the bamboo indigestible to insects.

Hardy’s father, John, a Canadian expat, was among the pioneers who pushed the practice to new heights in Indonesia. With his wife, he founded the all-bamboo campus of Green School in the jungles of Bali in 2006, and creating a lab for experimentation with bamboo building and engineering.

Together with a team of dozens, Hardy is continuing her father’s work. Born and raised in Bali, Hardy moved to US for college, but returned to Bali in 2010 to start Ibuku. “I’ve never wanted to focus on one medium or art form. The technical details are figured out in the team but I’m interested in the visual realm and how spaces feel and look,” says Hardy, who is the creative director in Ibuku.

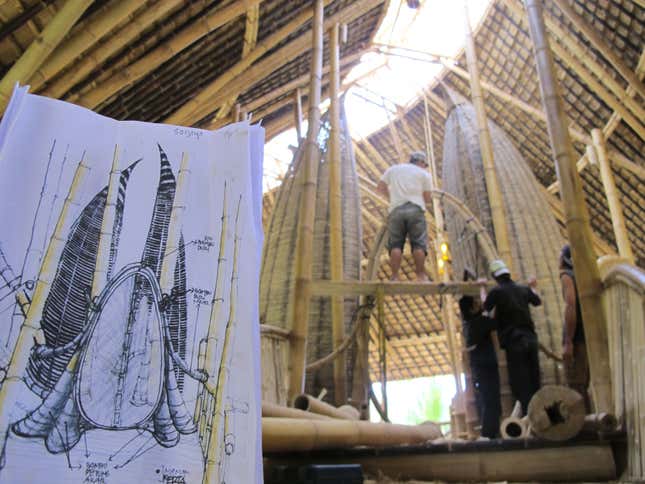

Ibuku’s 50-plus bespoke buildings in Indonesia are mostly handmade, showcasing the talent and ingenuity of locally-trained Indonesian architects, engineers, designers, artisans and craftsmen. “The architects in my team are the extraordinary outliers. They sought us out to be involved in something creative and unique. Some of them have been working with bamboo since their childhood creating temporary structures for Balinese cultural ceremonies, others are fresh out of architecture school and we just have to bend their minds out of a mindset wrought by an architectural education,” Hardy tells Quartz.

These structures are used as private residences, hotel villas and classrooms in Green School.

“The tried and true formulae of architecture do not apply here,” said Hardy. “It’s a challenge. How do you make a ceiling without flat boards? Let me tell you, there are days when I dream of sheet rock and plywood.”

Instead of blueprints, her team makes miniature 3D models of their buildings. Then they take this model to the site, and select a unique pole from the pile for each component.

But not everything has been solved.

The toilet acoustics remain a conundrum. “At night, I end up Googling ‘Japanese ladies noise modesty machines,’ ” Hardy tells Quartz. “There are still some things we’re working on, but one thing I learned is that bamboo will treat you well if you use it right.”