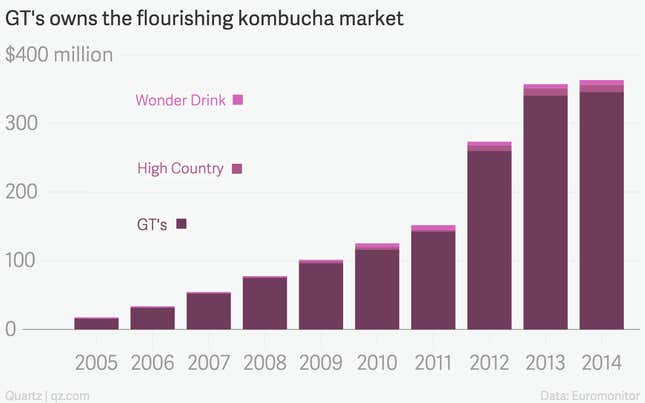

Move over, coconut water: US consumers bought nearly $400 million worth of carbonated, fermented tea—aka kombucha—in 2014.

A man named G.T. Dave can take credit for popularizing kombucha in the US. (His family credits the drink for curing G.T.’s mom, Laraine, of cancer in the 1990s.) GT’s Kombucha, the product line, rang up $346 million in sales in 2014.

A neat description of what kombucha is, exactly, can be found in a recent profile of Dave and his business in Inc. magazine:

If you’ve never tried kombucha, imagine drinking a sweet-tart cider vinegar that’s carbonated like beer and has a few little chunks swimming around in it. It’s made of slightly sweetened tea–green, black, or both–that ferments for up to a month while a mushroom-looking blob floats on top of it. The blob is the key ingredient. Known as a scoby (for symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast), it essentially eats the sugar, tannic acids, and caffeine in the tea, and creates a cocktail of live microorganisms that many believe to be beneficial. Scobys constantly grow and reproduce, and their offspring are something of a currency among kombucha devotees, who use them in homebrewing.

For gross pictures of kombucha skobys, which some home-brewers call “mothers,” see Buzzfeed’s “There’s Something Horrifying In That Kombucha You’re Drinking.”

Kombucha is driving most of the growth in ready-to-drink teas right now, according to analysts at Euromonitor. The drink’s taste is not naturally appealing to most people, but the purported health benefits of its probiotic cultures (it’s said to aid digestion, boost energy, and more) weigh heavily in its favor.

Kombucha may appear to have gone mainstream overnight, but as the chart above shows, that’s not exactly what happened. Several years passed between kombucha being (ironically) anointed “the most liberal product in America,” by the New Yorker’s culture editor, emerging in Hollywood, and eventually appearing on Walmart shelves. Natural foods enthusiasts have been brewing it at home for decades. In 2010, already a staple at Whole Foods and other nationwide retailers, kombucha made headlines after food inspectors noticed that some products contained as much as 2.5% alcohol by volume, prompting massive recalls. By the time GT’s had earned its place back on store shelves, other brands had entered the mix.

New makers of kombucha, such as Austin-based Kosmic Kombucha, force carbonate their brews to speed up production, a shortcut that GT’s is against. Chris Reed, CEO of the company that makes Reed’s Ginger Brew and Virgil’s Root Beer and is about to launch Reed’s Culture Club Kombucha, told Inc. that his product is force-carbonated, too: ”What’s the difference, whether a bug ate the sugar and farted out the CO2 or you added it yourself?”

That consumers will continue to eagerly buy kombucha for upwards of $5 a bottle—less expensive than cold-pressed juice, at least—seems to be a foregone conclusion. The question for industry watchers now is whether GT’s will retain its hold on the market.