Over the past two decades, the massive platforms of floating ice that dot the coast of Antarctica have been thinning and doing so at an increasing rate, likely at least in part because of global warming. Scientists are worried about its implications for significant sea level rise.

The ice shelves—some of which are larger than California and tens to hundreds of yards thick—are the linchpins of the Antarctic ice sheet system, holding back the millions of cubic miles of ice contained in the glaciers that flow into them, like doorstops. As the ice sheets thin, the massive rivers of ice behind them can surge forward into the sea.

Antarctica holds enough ice, if it all melted, to raise sea levels more than 200 feet. That would take hundreds to thousands of years, but the recent thinning of the ice shelves means that there has already been an increase in the rate of Antarctica’s contribution to sea level rise, and it’s accelerating.

While it was known that many ice shelves were thinning and glaciers were flowing faster to sea, this study is “another in a series of really blockbuster studies” that uses satellite data to show just how much and where Antarctica is changing, Ted Scambos, a glaciologist with the National Snow & Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado, said. Scambos was not involved with the study.

“There’s some very large changes that have added up,” study author Helen Amanda Fricker, a glaciologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, said.

Delicate balance

The melting of ice shelves or the breaking off of icebergs aren’t themselves signs of climate change. They’re natural processes that help keep the mass of a glacier in balance: Snow that falls in the continent’s interior adds ice to the glacier, while ice shelf melt and iceberg calving keep the glacier in balance by losing about the same amount of ice that is added.

The problem comes when the ice shelves lose more mass than the glaciers are gaining.

“The ice shelves shouldn’t be losing volume if they’re in balance,” Fricker said.

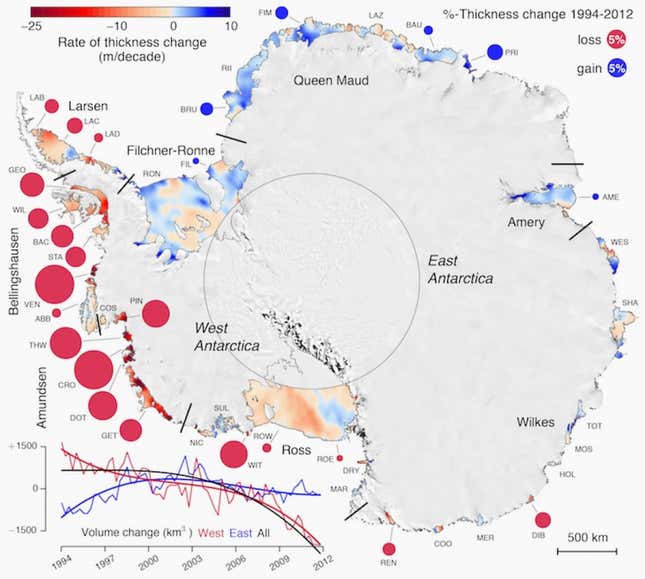

This balance is what Fricker and her graduate student Fernando Paolo were looking at when they stitched together 18 years of satellite data (from 1994 to 2012) from three overlapping European Space Agency missions that measured the volume of Antarctica’s ice shelves with radar altimetry.

What they found was that the massive ice shelves were losing, on the whole, about 30 to 50 cubic miles of ice per year over that span. And in that period, the rate of ice loss accelerated by an average of seven cubic miles per year.

“So there’s a loss, but that loss is increasing,” said Fernando Paolo, the lead author of the study that was detailed in the March 27 issue of the journal Science.

The study, all three scientists said, shows how crucial information on this kind of long timescale is for seeing the big picture of Antarctic melt; with a study that only lasts for a few years, “some of the ice shelves are not really responding in the way that they would over the long term,” Fricker said.

“A big loss”

The story varies for specific glaciers and the different regions of Antarctica, with much more ice loss in West Antarctica than East Antarctica and for particular glaciers in the west.

West Antarctica has been a major focus of south polar climate research, in part because of the clear signs of melt there as well as some spectacular ice shelf collapses in recent decades.

As a whole, that half of the continent has seen a 70% increase in its average rate of loss from ice shelves, the satellite data showed. The Amundsen and Bellingshausen sea areas had particularly high rates of loss; while the two regions account for less than 20% of West Antarctica’s ice shelf area, they contributed more than 85% of the volume lost there over the study period.

One particular glacier in the Amundsen embayment lost 18% of its thickness over the 18 years of the study.

For an ice shelf that, like all the others, has been in place for hundreds of thousands of years, “that’s a big loss,” Paolo said.

East Antarctica, meanwhile, has until recently been thought to be more stable, as its glaciers rest on land that is above sea level and the waters surrounding it are thought to be cooler. Recent research has showed that there is still much to learn about the susceptibility of the glaciers in East Antarctica, which holds much more ice than the west. Totten Glacier was recently shown to have channels in the seabed beneath it that would make it much more vulnerable to an influx of warm water than previously thought, though such warm water hasn’t yet been detected there.

The satellite data in the new study showed that for the first part of the study period, East Antarctic glaciers gained mass overall, then that trend flat lined in the second half of the time period. At the level of individual glaciers, some have still been gaining mass, while others, like Totten, have thinned.

The leveling off of the East Antarctic ice shelf rates suggests that more attention needs to be paid to the eastern half of the continent because “if you turn your back on the ice shelves that are not changing” then you might miss something if suddenly start to, Fricker said.

“Boots on the ice”

Having this kind of long-term record on Antarctic ice shelf thinning is key to understanding what processes are behind the thinning and how they might continue into the future.

In West Antarctica, it is thought that most of the thinning is caused by warm waters that are eating away at the ice shelves from below, a consequence of changes in prevailing winds that is potentially linked to global warming.

Paolo and Fricker said the data show the characteristic signature of this kind of melt, which happens at what is called the grounding line, or the point where the glacier last touches land and the ice shelf begins. Other recent studies examining glaciers have also bolstered this idea, and have even suggested that some glaciers in West Antarctica have reached a point where their retreat and melt is now irreversible.

The picture is murkier in the east, in part because so much less work has been done there. This study shows, though, that East Antarctic ice shelves “are actually subject to large changes as well,” Paolo said.

The biggest rates of ice loss seen in the Amundsen embayment imply that some of those ice shelves, if they continue at the same rates, could be gone within a century. Of course, “what’s going to happen 100 years from now, we cannot know,” Paolo said, which is why it’s so important to understand exactly “what are the causes, the mechanisms, behind the changes we see.”

For that, you need what Scambos calls “boots on the ice”—missions that put researchers and equipment onto the ice shelves to get more detailed information about the forces pushing them around.

That’s not an easy sell, because “the Antarctic environment is perhaps one of the most difficult environments to work,” Paolo said. But there are hopes that new satellite missions, along with remotely operated submarines and other technology can help build our knowledge of the forces at play in the southernmost continent.

As this study makes clear, Scambos said, we need continuous monitoring of this environment because “we’re faced with a planet that is changing in ways we don’t want.

This post originally appeared at Climate Central.