Update (Dec. 18, 6:25 a.m.): Cerberus said it is putting its portfolio of gun companies, known as Freedom Group, up for sale. Read the press release here, or read below for excerpts.

Original Post (Dec. 17, 6:00 p.m.): Trace the semiautomatic assault rifle used in Friday’s slaughter in Newtown, Connecticut, to its origin—back to the store where it was bought, the factory where it was produced, and the companies that profited from its sale—and you’ll end up in the Midtown Manhattan headquarters of a private equity firm named after a mythical three-headed dog that guards the entrance to the underworld.

And it’s there, at the office of Cerberus Capital Management, where the future of firearms in the United States is likely to turn.

Cerberus quietly dominates the American gun industry, selling more firearms and ammunition in the US than anyone else. In 2008, by its own account, Cerberus’s Freedom Group sold half of the nation’s semiautomatic rifles along with 37% of traditional rifles, 31% of shotguns, and 33% of ammunition. All told, Freedom Group says it sold 1.2 million long guns and 2.6 billion bullets in the 12 months between April 2009 and March 2010, the most recent year for which data is available, generating $846 million in revenue.

How Cerberus, which is perhaps best known for being little-known, came to be the main player in the world’s biggest gun market speaks to dicey business of manufacturing firearms and the darker aspects of private equity. Cerberus didn’t return messages seeking comment.

Bushmaster Firearms—the company whose AR-15 style rifle has been used in mass shootings from Newtown to Aurora, Colorado—began as a producer of pistols for Air Force pilots shot down over enemy territory. Richard Dyke purchased the company in 1978 and turned its focus to more powerful weapons with larger magazines, including the AR-15, a version of which is pictured above, and its equivalent for military and police, the M-16. By 2005, the company was doing $65 million in sales but didn’t see a way to grow further.

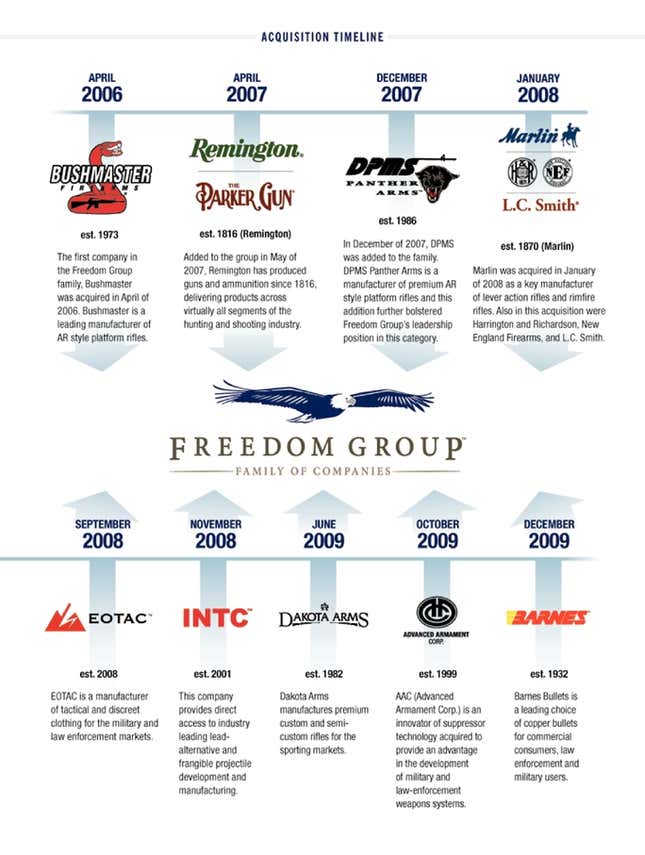

Cerberus had never owned a gun company, but it thought it could provide Bushmaster with a classic private-equity solution: tighter management and a tie-up with similar companies. Cerberus bought Bushmaster in 2006 for an undisclosed sum, formed Freedom Group as a holding company for its firearms business, and then went shopping. Here is the spree of acquisitions as detailed in a regulatory filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission:

That filing came in 2010 as Cerberus, then hobbled by poor investments in carmaker Chrysler and mortgage lender GMAC, attempted to cash out of the gun business by taking Freedom Group public. “After bad bets on cars and home loans, Cerberus Capital Management is turning to guns and bullets,” began a Wall Street Journal story about the offering. And this is how Freedom Group made the case for its future growth to potential investors:

We believe that a meaningful percentage of current firearm sales are being made to first time gun purchasers, particularly women. We further believe that the introduction of first time shooters, as well as the renewed interest of many existing shooters, will translate to increased participation across the ever-widening array of shooting sports. In addition, the continued adoption of the modern sporting rifle has led to increased growth in the long gun market, especially with a younger demographic of users and those who like to customize or upgrade their firearms.

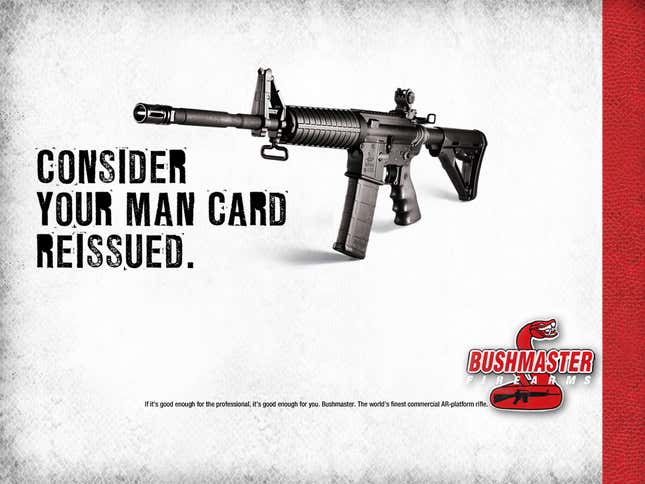

Modern sporting rifles include the kind used in the Newtown attack. They’ve been a source of growth, particularly among young men, in an industry that has otherwise struggled to find new customers. Take, for instance, this Bushmaster marketing campaign targeting male insecurities:

Cerberus withdrew the IPO for Freedom Group in April 2011 as gun sales slumped, but the prospectus it left behind provides a view that would otherwise be missing of the firearm conglomerate. In addition to the data recounted above, Freedom Group disclosed that it made 58% of its revenue ($482 million) from firearms in the 12 months between April 2009 and March 2010 with a gross profit margin of 32%.

That’s an impressive margin, achieved by consolidating production among its various brands. For instance, management installed by Cerberus closed Bushmaster’s longtime factory in Windham, Maine, and began producing those rifles in an existing Remington plant.

Another 40% ($330 million) of Freedom Group’s business was attributed to ammunition, with an even better margin of 36%. Selling both guns and bullets is a strategic advantage for the company, it claimed: “As the only major supplier of both firearms and ammunition in the United States, we believe our ability to sell ammunition creates a unique competitive advantage within the industry and allows us to solidify and extend our existing long-term relationship with our loyal customer base.”

Freedom Group saw military and law enforcement, which accounted for 16% of its business in 2009, as a large area of growth, naming among its existing customers the US, Colombia, Georgia, Italy, Poland, Malaysia, Mexico, and Oman. Sales to governments could become even more crucial if, in the wake of the Newtown massacre, the US follows other countries in severely restricting or perhaps even banning the kind of semiautomatic rifles that have proven so profitable for Bushmaster and, thus, Freedom Group and Cerberus.

Indeed, Freedom Group has perhaps the most to lose from the kind of gun regulation being proposed in the wake of the Newtown shooting—and behind which President Barack Obama, previously non-committal on the issue, seemed to throw his weight in a powerful speech on Sunday. In the filing for its aborted IPO, Freedom Group not surprisingly listed gun control as a threat to its future growth, specifically mentioning the US Assault Weapons Ban (AWB) that was enacted in 1994 and expired in 2004: “If a statute similar to AWB were to be re-enacted”—as has been proposed by lawmakers in recent days—”it could have a material adverse effect on our business.”

In fighting further gun regulation, the company has a friend in the National Rifle Association, which last year assured its members, ”NRA has had contact with officials from Cerberus and Freedom Group for some time. The owners and investors involved are strong supporters of the Second Amendment and are avid hunters and shooters.” The NRA issued that statement to rebut rumors that Freedom Group, viewed as shadowy even among gun enthusiasts, was controlled by liberal financier George Soros.

And as the New York Times reported last year:

Cerberus brings some connections to the table. The longtime chairman of its global investments group is Dan Quayle, the former vice president. The Freedom Group, meantime, has added two retired generals to its board. One is George A. Joulwan, who retired from the Army after serving as Supreme Allied Commander of Europe. The other is Michael W. Hagee, formerly commandant of the Marine Corps.

In the current political climate, Cerberus will need more than Dan Quayle and a few retired generals to combat further gun regulation. We’ll soon see how fiercely—and publicly—the publicity-shy private equity firm is willing to fight to protect its investments.

Update (Dec. 18, 6:45 a.m.): In its statement announcing the sale of Freedom Group, Cerberus said:

As a Firm, we are investors, not statesmen or policy makers. Our role is to make investments on behalf of our clients who are comprised of the pension plans of firemen, teachers, policemen and other municipal workers and unions, endowments, and other institutions and individuals. It is not our role to take positions, or attempt to shape or influence the gun control policy debate. That is the job of our federal and state legislators.

There are, however, actions that we as a firm can take. Accordingly, we have determined to immediately engage in a formal process to sell our investment in Freedom Group. We will retain a financial advisor to design and execute a process to sell our interests in Freedom Group, and we will then return that capital to our investors. We believe that this decision allows us to meet our obligations to the investors whose interests we are entrusted to protect without being drawn into the national debate that is more properly pursued by those with the formal charter and public responsibility to do so.