Over the past decade, Poland’s economy has consistently expanded at one of the fastest rates in Europe. It was the only country to avoid a recession during the 2008 crash and the ensuing financial crisis. Much of the credit goes to Poland’s policymakers, and it’s worth looking at what was done to see what others can learn.

First, we hear from Leszek Balcerowicz, a former Polish central banker and long-time economic policymaker who helped drag his country out of its post-Soviet malaise. He’s argues against the loose monetary policy of the United States and the European Central Bank’s efforts to rescue financially-troubled European countries:

First, Bernanke-style policies “weaken incentives for politicians to pursue structural reforms, including fiscal reforms,” he says. “They can maintain large deficits at low current rates.” It indulges the preference of many Western politicians for stimulus spending. It means they don’t have to grapple as seriously with difficult choices, say, on Medicare…Another unappreciated consequence of easy money, according to Mr. Balcerowicz, is the easing of pressure on the private economy to restructure. With low interest rates, large companies “can just refinance their loans,” he says. Banks are happy to go along. Adjustments are delayed, markets distorted.

That’s certainly an interesting argument, but it doesn’t really get into the situation in Poland during the crisis. That might be because Poland did, in effect, precisely what Balcerwoicz says is such a bad idea: It rapidly devalued its currency and launched a fiscal stimulus program.

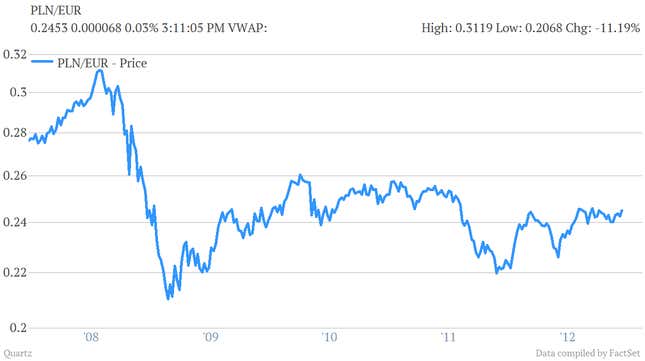

This was a result of the fact that Poland controls its own currency and never pegged it to the euro. As the Economist explains, Poland was exposed to the same intra-European capital flows that overwhelmed Greece and other peripheral states. However, this debt was denominated in zloty and not euros, so the rush to pull money out of the country during the crisis resulted in Poland’s currency depreciating against that of its neighbors, creating a massive stimulus effect. Poor Greece, meanwhile, saw money flow out of its country, but its currency—the euro—remained uncompetitive.

At the same time, governments launched the Vienna Initiative, a program to bolster West-to-East lending in Europe, while Poland’s government allowed budget deficits grew from less than 2% of GDP to 8% during the crisis. This is a fairly standard counter-cyclical economic policy playbook, and contrary to Balcerowicz’s assertions, the government’s rejection of austerity hasn’t yet prevented the country from getting on the path to fiscal consolidation, but it has spared the country the human and economic costs of extended under-performance.

What can we take away from the Polish experience?

One, ironically enough, that Balcerowicz’s warnings against ideology apply across the board. His tight money policy as a central banker from 2002 to 2007 (and Polish banks’ strict lending standards) likely helped Poland avoid asset bubbles as the country was awash in foreign credit from 2004-8, but would have likely been problematic if adopted during the crisis.

Two, that structures can be as important as decision-making: The institutions Balcerowicz helped create as a liberalizing reformer in the nineties, particularly a free-floating currency, were key to the robust performance of his country during the crisis.

And finally, that austerity doesn’t necessarily create the best climate for structural reform: It’s easy to criticize Greece, as Balcerwociz does, for being slow to adopt changes to its labor markets and social contract, but those kinds of changes often require accommodating monetary policy to diminish their economic and political costs.