BOGOTA, COLOMBIA—In the tiny barrio of San Luis, perched precipitously on the hills above Bogotá, a hundred university students are hard at work. Split into 10 groups, they glue, drill and screw things together to make 50 low-cost street lights.

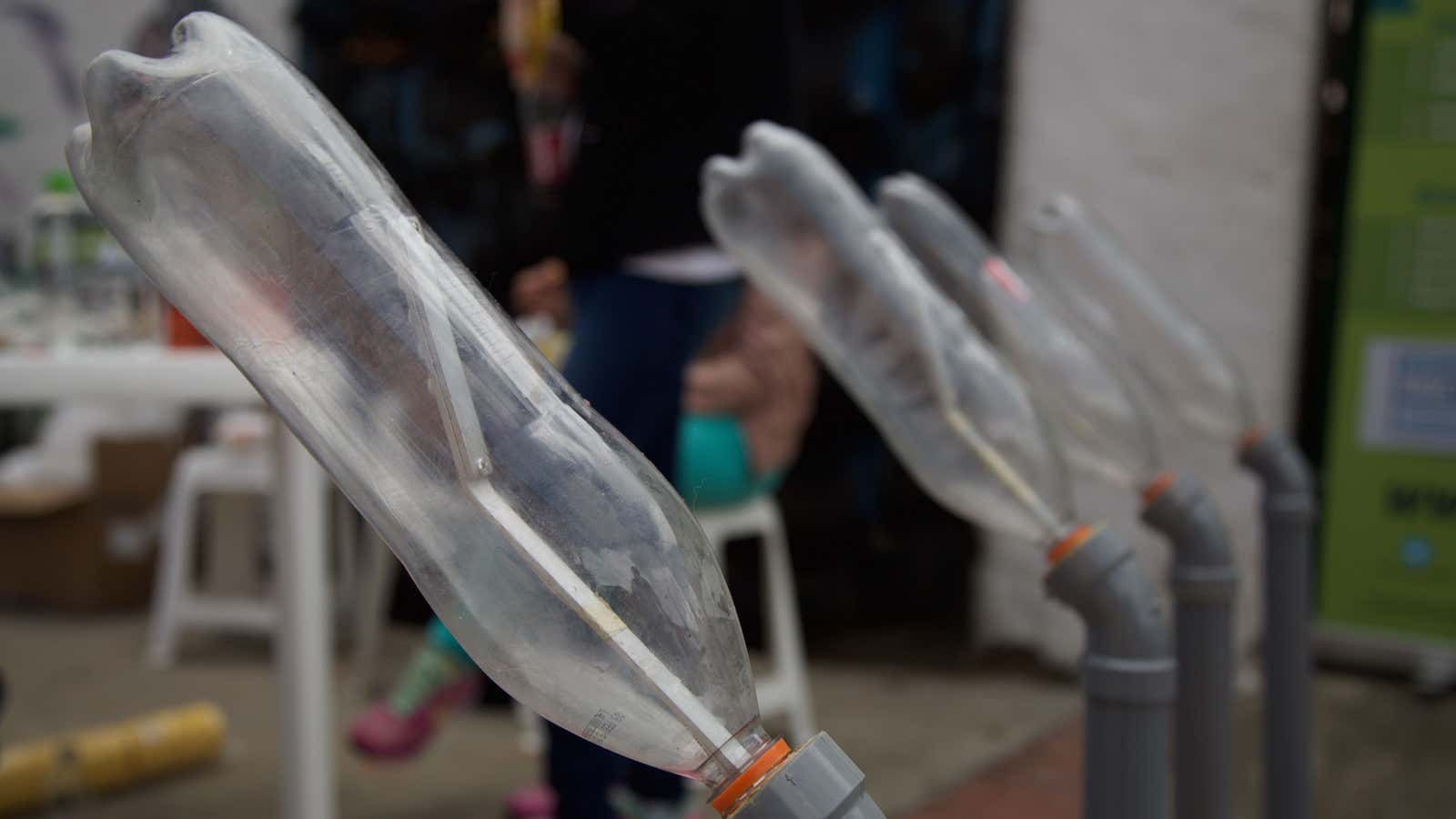

The lights’ beauty lies in their simplicity: A 3-watt LED lamp is connected to a controller and a battery pack, which is powered by a small solar panel. The light fixture’s protective casing is an old plastic soda bottle. Each lamp costs around 176,000 Colombian pesos ($70) to build, and nothing to run. Parts are sourced locally and the battery can power the lamp for three consecutive nights without charging. Once completed, the students install the lights throughout the neighbourhood, brightening dimly lit alleyways and dark clearings.

It’s the latest project from Liter of Light, an NGO which illuminates communities in the developing world. Illac Diaz, the organisation’s Filipino founder, was a student at MIT when he came across the “Moser lamp”, invented by a Brazilian mechanic, Alfredo Moser. He had found that by filling an old plastic bottle with water and inserting it into people’s roofs you could refract sunlight into their homes, creating a light with a brightness equivalent to a 55w electric bulb. Inspired by the design, Diaz returned to the Philippines in 2011 to found Liter of Light. So far it has lit up 28,000 homes in Manila alone and many thousands more across the world. Last year it went a step further, developing solar-powered street lights that can brighten public spaces too.

What makes Liter of Light’s approach stand out is its open-source, easily replicated technology. In the past, efforts to bring light to remote communities have been hampered by the cost of importing expensive parts. “During an emergency if you want a thousand lights, it takes five months to order them from China or India and another two or three months to bring it over by ship”, says Diaz. Once installed, lights are prone to break after a year or two, and without someone on hand to repair them, the expensive technology becomes redundant.

Liter of Light is trying to devolve and simplify the process. It share its designs with everyone, publishing how-to videos on YouTube that enable communities to build their own lights. The parts are cheap and the circuit board can be made using a marker pen. The NGO now has 53 chapters around the world, who between them have installed over 250,000 bottle lights and over 15,000 night lights. Each chapter is self-sufficient: Illac Diaz had only met the Colombian team once before and has never met the organisers in Ethiopia.

The neighbourhood of San Luis is ideal for the project. Located in a dark, forgotten part of Bogotá, it’s home to around 16,000 residents, many of whom arrived after being forcibly displaced by Colombia’s civil war. Their homes were built without planning permission and their families get little in the way of state attention or public services. Unemployment is high and the dark alleyways are a magnet for drug traffickersmicro-traffickers. Public lighting is scarce or non-existent, posing a particular threat to women and girls, many of whom face sexual harassment or worse. “We need to create a safer environment for women and girls who live in these places”, says Diaz. “Street lights are the first step in creating a safer community.”

Darkness doesn’t just cause problems in Colombia. According to the UN, 1.5 billion people around the world have to make do either with very poor quality light or no light at all. There are 1.3 billion who rely on kerosene lamps which emit toxic fumes, causing respiratory illnesses such as asthma, bronchitis and pneumonia. Inhaling kerosene smoke is equivalent to smoking four packets of cigarettes a day and kills an estimated 1.5 million people each year.

A lack of light also stunts education. Children who have to work to earn money for their families during the day—as many do in poorer countries—can’t study without light in the evenings. Unesco is calling 2015 the “International Year of Light” in an effort to draw attention to the issue.

As well as the new technology, Liter of Light also brings a different philosophy to street lighting. It installs more lights across a wider area rather than bunching a few bright lights in one central location, such as a town square. The organization says this approach reduces crime by 60-70%. “We put them in front of shops, so people can get more sales and see what’s happening in the street.” says Diaz. “Instead of bigger, brighter lights we prefer smaller, cheaper ones.” That particularly helps women. As developing countries establish 24/7 economies, women are an increasingly active part of the workforce and are especially vulnerable when commuting after dark.

As well as tackling crime, public lighting can also make a big difference in the aftermath of a natural disaster. When Typhoon Haiyan battered the Philippines in November 2013, Liter of Light lit up over 2,000 homes in the some of the hardest-hit areas. In Pakistan last year a hundred street lights were installed at the UN’s Jalozai refugee camp in Pakistan, supporting 10,000 families who had fled the Afghan war. The camp is due to receive another 450 lights this year. In Egypt, the NGO is teaming up with Pepsi to light 35 schools in an effort to alleviate the blackouts associated with the country’s energy crisis.

Pepsi is also helping to raise funds for the organisation more generally. It recently teamed up with the designer Nicola Formichetti, who made a luminous dress made out of plastic bottles in an effort to “shine a light on those who live in darkness”. As part of its new marketing drive, the company has also promised to donate a dollar to Liter of Light every time someone includes the hashtag #PepsiChallenge on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter or YouTube.

That could give extra fizz to the programme in Latin America, which is already growing very quickly. In Colombia, 14 locations have already been illuminated and there are plans to install another 2,000 street lights across the country in 2015. The organisation also hope to expand the programme to Mexico, Peru and Brazil. Across the world, Liter of Light has pledged to install a million new lights this year.