In the years following the 2008 financial crisis, the global-billionaire class boomed in both size and aggregate wealth. With that, Mykolas Rambus saw a business opportunity.

Forbes Media (where Rambus served as chief intelligence officer from 2007 to 2010) could repackage the data behind its definitive World’s Billionaire List, and sell it to organizations interested in finding better ways into the pockets of wealthy individuals. Still struggling amidst a recessionary climate, Forbes’s management rejected the proposal. In 2010 Rambus left to create his own company.

“No one really knew, until Wealth-X came along, just how much money was in the hands of the world’s super rich,” Rambus wrote in a company blog post published last year. Describing the untapped opportunity, he claimed “the wind [is] at our backs… and five global wealth trends—Wall Street rebalancing, non-profit urgency, luxury brand segmentation, massive wealth transfer, and global wealth creation—are playing directly into our hands.”

Wealth-X (and competitors like Wealth Insight, WealthEngine, and Relationship Science) are constructing “social maps” of the world’s wealthiest individuals, compiling extensive amounts of personal information—including background details (e.g., education, residences, family history) and associated histories that could only exist for a certain kind of person (e.g. “significant litigation,” “private foundations,” “known associates,” etc.).

Billionaire behaviors and characteristics can indeed more closely resemble that of a company than a person—a twist on the proverbial “corporations as people” debate. Managing massive amounts of wealth turns out to be a life-consuming task, and these individuals rely on an entourage of support staff and allied partners, often employing private offices and outsourced “chief operating officers.” Business magnate Michael Dell established MSD Capital to manage his family’s newfound wealth, and the Walton family’s massive fortune has long been managed through Walton Enterprises LLC.

Wealth-X and its competitors are building this fabric of personal and professional relationships into their social maps, hoping the broader context will prove valuable to interested parties, such as luxury marketers, universities, and major charities.

Dispatches from these industry players offer amusing, and sometimes aggravating glimpses into the dizzying lifestyle of the global-billionaire class. Research from luxury car-maker Rolls-Royce found that billionaires have “on average eight cars and three or four homes… three-quarters own a jet aircraft and most have a yacht.”

Douglas Gollan, founder of Elite Traveler magazine, reported in MediaPost about an internal survey of private-jet owners that found a yearly average spend of six figures on watches, a quarter million on jewelry, and over half a million on home renovations.

“We are catering to a client that can afford anything; [they] want what they want when they want it, and we’re always saying yes,” Bill Fischer, a luxury travel advisor, told Fox Business.

Luxury companies regularly undertake logistical somersaults and elaborate persuasions to court these highly-demanding individuals, an effort that can border on the satirical. Fischer confided a personal experience about a hotel that literally knocked down walls to create a three-bedroom suite for his client (who wouldn’t accept any two-bedroom options). Many world-class brands, such as Hermès and Christolfe, are constantly introducing ever-more exclusive clubs to ensure that their customers feel a consistent, heightened sense of “specialness.”

“The irony but also allure about [these] clubs is that no one knows the exact list of clients (other than the corporate staff), but also no one can ask to be allowed into the club,” writes Thomaï Serdari, a professor of marketing at New York University’s Stern School of Business in an email to Quartz. Serdari is the editor of Luxury: History, Culture, Consumption.. “In other words, one may be a member without knowing it.”

Many aspects of the billionaire market defy common sensibilities. In 2013, The Economist reported on the rise of “freeports”—warehouses built in capitalist-friendly urban zones around the world—which exploit legal loopholes by storing high-value assets in a way that is classified as “in transit,” securing numerous tax advantages and anonymity for clients. Wealthy individuals themselves are a peculiar kind of nomad, living not so much in a specific place as within an obscure socioeconomic stratosphere. Executives at luxury goods conglomerate Richemont have described them as “the homeless with 20 homes.”

The sobering reality underlying cartoonish billionaire lifestyles is that this narrow group represents a significant portion of the overall global economy. Data from Credit Suisse (featured in the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda) reveal that the aggregate wealth of the world’s 1% accounts for close to half of total global wealth.

This already-outsized economic influence is expected to grow even more. The Boston Consulting Group’s latest research forecasts that billionaire wealth will increase twice as fast as the global average over the next five years. Research from Oxfam found that the world’s number of billionaires has doubled since the financial crisis of 2008, and Rambus predicts the number will double again over the next decade.

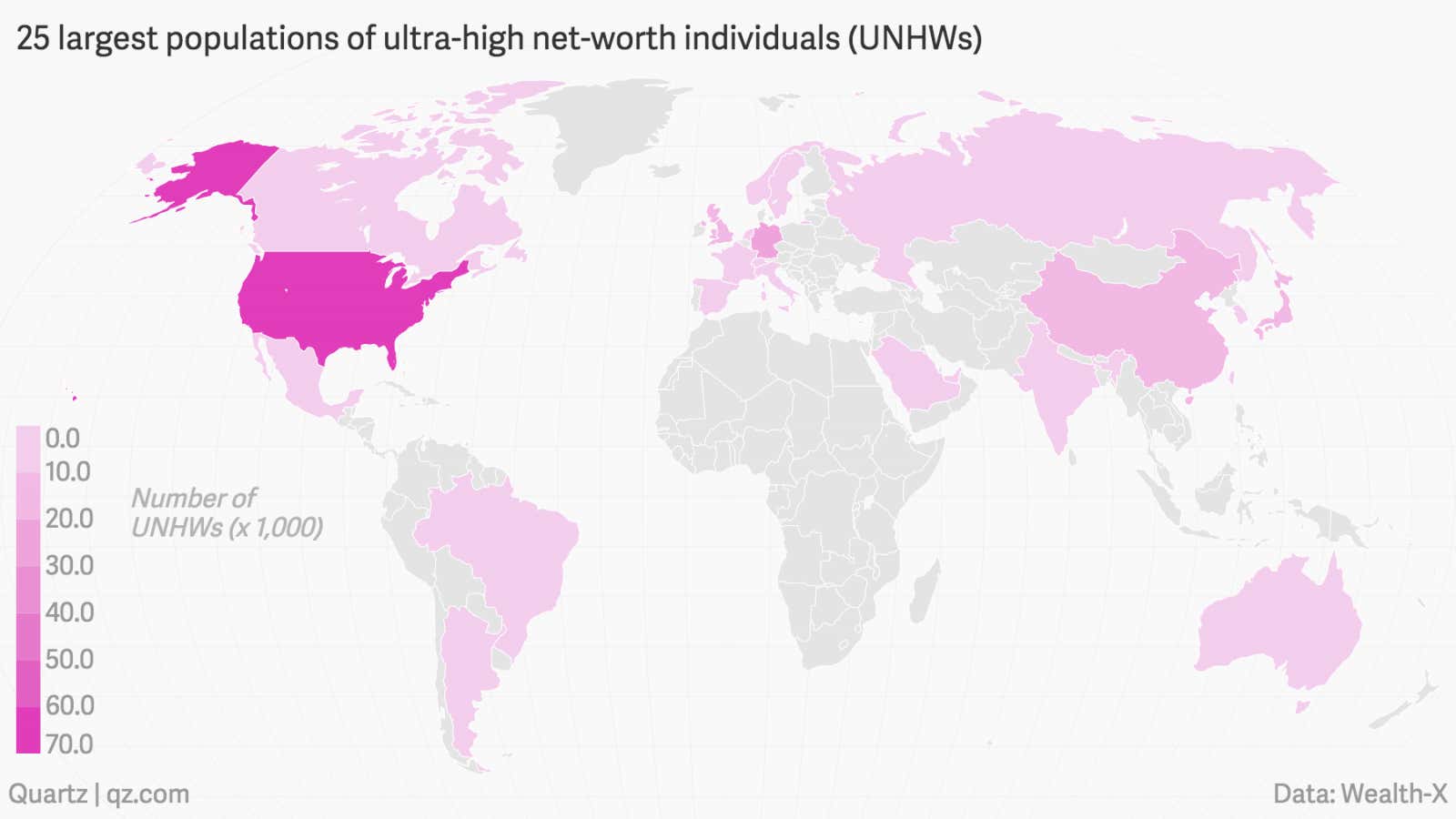

Polarizing inequality means that the biggest opportunity for wealth-intelligence firms is at the tip of the economic pyramid. Wealth-X made this explicitly clear in its early reports, which introduced a newly-defined upper-subset of the wealthy population called “ultra-high net-worth individuals” (UHNWs), whose net worth totals at least $30 million USD (a considerable leap from the $1 million necessary to be a “high net-worth individual,” or HNW. The company has since narrowed its focus even further, rolling out an annual Billionaire Census in partnership with global investment bank UBS.

Such a disproportionate wealth distribution legitimizes the concern that action or regulation against billionaires could have an unexpected impact on the global economy. Wealth-X’s public remarks on inequality follow this line of thought, including its critique of a hypothetical global tax on capital, which was the main antidote proposed by Thomas Piketty’s blockbuster book Capital in the Twenty First Century.

“The rich are getting richer, but taxing them might have dramatic and unpredictable consequences,” the company said in its official response to Capital. Wealth-X instead hopes that, driven by increasing public scrutiny and the peer-pressure of role models like Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, the “generous philanthropy” of the world’s billionaires can represent “an alternative to taxation.”

Public awareness around inequality has risen sharply since the financial crisis. While the World Economic Forum in 2010 prescribed inequality as the “most underestimated” global risk, a 2014 Pew report found that a broad majority of citizens across both developing and developed countries now see inequality as a major problem. What this massive shift in public opinion could mean or lead to in practical terms is still unclear, especially given the austerity and political gridlock still plaguing many of the world’s liberal governments.

“The gap of inequality is steadily increasing and one cannot yet articulate the event that will cause the reversal of that phenomenon,” Professor Serdari writes. “[But] it seems that the new [generation] of consumers, regardless of socioeconomic background, is much more grounded and concerned with bigger issues that affect life on the planet.”

Wealth-X identified “massive wealth transfers” as one of its driving global trends, an imminent transaction between generations that will put new money on the table for potential reallocation. As massive inheritances are passed onto younger, arguably more conscientious heirs, there may be an opportunity for Wealth-X to promote its “alternative to taxation” solution by advocating for stronger and smarter philanthropic efforts amongst the ultra-rich.

Even the tiniest contribution from this population could eradicate widespread global disparities. Oxfam’s seven-point plan on inequality (which could have served as a compelling manifesto for the Occupy movement) includes a proposal for a 1.5% billionaire tax (or “donation”) that would raise enough money to put every child in school and fund health services throughout the world’s poorest countries.

The social maps of Wealth-X and its competitors were designed to facilitate commerce amongst the billionaire class, but they can also catalyze philanthropic efforts to help improve the world. Previous generations of ultra-wealthy individuals may have spent their time perusing glossy magazines, filled with advertisements for gold watches and diamond jewelry, while flying in luxury jets to their private islands. But if the Pew polls and analysts like professor Serdari have detected a real shift in sentiment, maybe the next generation will engage in more altruistic pursuits.