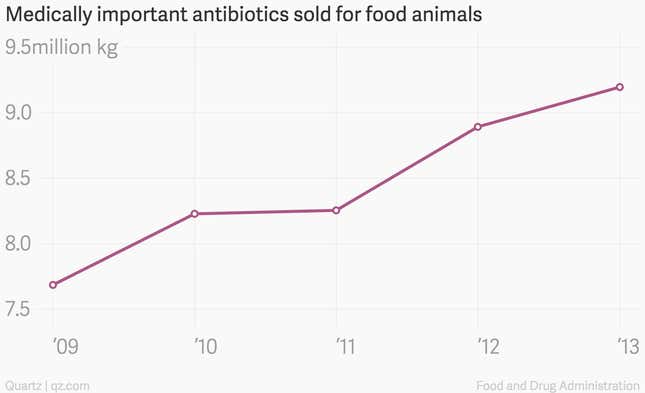

Evidence about the dangers of antibiotic use in livestock and its connection to resistance in humans is sufficiently compelling that groups as weighty as the World Heath Organization, the US Centers for Disease Control, and the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology have sounded the alarm. It prompted the US Food and Drug Agency to make an initial call for a voluntary reduction in 2012. But the amount of antibiotics bought for food animals in the US continues to rise:

An FDA report on the sales of the drugs for food animals found that between 2009 and 2013, sales increased 17%. Even worse, sales of antibiotics medically important to humans, including common ones like penicillin and tetracycline, went up 20%.

Livestock producers use antibiotics preventatively to keep animals from getting sick and spreading illness. They also use them to promote weight gain, allowing animals to get fatter faster, and with less food.

Figures for the actual use of antibiotics in livestock are not available because producers are not legally required to report them, though a September 2014 Reuters investigation found their use in poultry farms was “pervasive.” In 2011, the FDA confirmed calculations that showed that 80% of antibiotics sold in the US were destined for food animals.

The use of the drugs in food animals has been connected to the rise of superbugs, the antibiotic-resistant pathogens that a recent report commissioned by the UK prime minister found may be responsible for up to 700,000 deaths worldwide each year—and predicted could kill more than 10 million people per year by 2050 if the problem is not “tackled.” Long used drugs like penicillin are simply no longer as effective as they once were.

By regularly administering low doses of antibiotics to animals in confinement operations, farmers kill most of the bacteria the animal may be susceptible to. But health organizations and researchers believe this practice may be also leaving the strongest—and therefore, most dangerous—pathogens behind. Those “superbugs” then breed with each other, creating a new class of bacteria that resists the drugs.

Drawing a definitive, linear connection between a specific agricultural use and a particular human illness has been elusive. But several recent studies are closing that gap.

In September 2013, researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Health published the first study showing a direct connection. Drawing on a population of 446,000 Pennsylvania residents living near hog confinement operations and the fields where those operations spread their manure, researchers reviewed cases of more than 50,000 skin infections. They also tested samples from the nearby fields, which contained antibiotic-resistant bacteria, resistance genes, and about 75% of the antibiotics the hogs had consumed. The study concluded that there was a “significant association” between the infections and the fertilized fields, as well as a “similar but weaker association” between the infections and the farms.

Most recently, Texas Tech researchers reported on an analysis of the particulate matter (floating dirt and poop particles) downwind from 10 beef cattle feedlots within a 200-mile radius of Lubbock, Texas. The matter contained harmful bacteria, antibiotics and “microbial communities” with higher levels of antibiotic resistant genes. Antibiotic resistance has gone airborne.

The FDA’s December 2013 final guidance asks pharmaceutical companies to voluntarily change their antibiotics labels to designate the drugs only for therapeutic, and not weight gain, purposes. But this effort relies on the willingness of manufacturers to make those changes, and for the livestock industry to heed them. Whether or not that faith in voluntary action is well placed remains to be seen.