Scientists prefer women to similarly qualified men for tenure-track faculty positions, according to a new experiment published in Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences (PNAS).

Cornell University researchers Wendy Williams and Stephen Ceci sent narrative summaries of hypothetical male and female tenure-track applicants to 873 science and engineering faculty across the US. Across a wide variety of conditions spanning five experiments, faculty raters selected female applicants over male applicants by a factor of two to one.

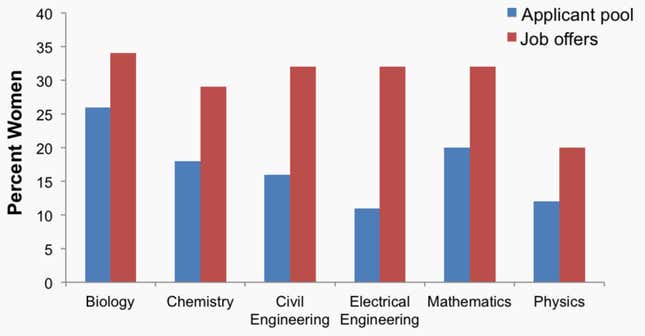

The new experimental results echo earlier real-world data about faculty hiring. A 2010 National Research Council report, for instance, found that the proportion of women among tenure-track applicants increased substantially as jobseekers advanced through the process from applying to receiving job offers in six STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) fields.

The new results that paint a rosier picture of gender equity in STEM hiring, however, seem to contradict earlier studies such as a 2012 PNAS study that found gender biases favoring male college graduates applying for lab manager positions.

However, Williams and Ceci argue that these results aren’t contradictory at all. Gender bias may not occur when applicants’ records “are clearly strong, as is the case with tenure-track hiring,” they write. However, bias may emerge when evidence for applicants’ competence is more mixed.

A recent quantitative synthesis of 136 other gender bias experiments supports the researchers’ argument. The review found that raters preferred men for male-dominated jobs such as architect and electrician when ratees were described as having average or ambiguous competence (meaning raters received mixed information that suggested both low and high competence). However, “neither gender was favored when ratees were highly competent.”

But the quantitative review also found that “bias varied substantially across studies,” meaning that some situations favored men while others favored women. The new PNAS study contributes to this research base by identifying an academic hiring context that favored women.

Authors of the PNAS study argue that some other academic contexts such as grant funding and tenure review are also not biased against women, but the authors nevertheless acknowledge that “women may encounter sexism before and during graduate training.”

The earlier 2012 PNAS study, for instance, found that science professors offered less mentoring to female than male college graduates. The hypothetical female students received less encouragement to stay in their field and pursue research careers.

Nevertheless, subsequent studies suggest that many women persist in STEM despite these biases.

Academic fields that have greater gender bias do not have fewer women at the PhD or faculty level, according to a 2014 experiment involving 6,548 professors. For instance, biases against white women were larger in health sciences than in the male-dominated fields of engineering and computer science.

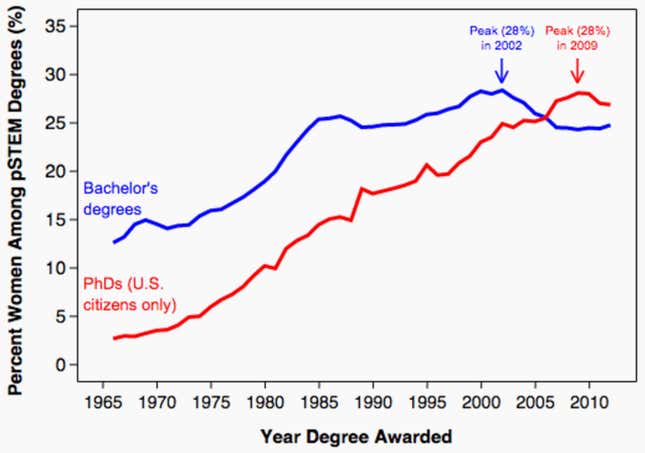

Women and men indeed now persist in STEM at equal rates from the bachelor’s to PhD degree, according to my recent study with Jonathan Wai of Duke University Talent Identification Program.

We found gender gaps in STEM persistence among college graduates in the 1970s and 1980s, but not among more recent graduates. A recent Council of Graduate Schools report further supports this conclusion.

I agree with Williams and Ceci when they say these findings don’t “minimize the importance of anti-female bias where it exists.“ But the findings do suggest that biases in graduate mentoring do not substantially impede women’s progress in STEM.

In fact, women’s representation in math-intensive STEM fields is now higher at the PhD and assistant professor level than the bachelor’s level.

Yet women are still scarce in some STEM fields, as Melinda Gates noted in a tweet referencing my study.

Women are underrepresented in these fields because of factors such as cultural beliefs that operate at the bachelor’s level and below—not because of bias in tenure-track hiring or graduate mentoring.

These remaining representation gaps mean that policymakers should not use studies such as mine and the new PNAS paper to say their work is done. Rather, these studies simply inform a new way forward.

The PNAS study shows that continued efforts to correct anti-female biases in tenure-track hiring are likely misguided. The message has already gotten through at that level. Resources spent on those efforts would instead be better directed toward contexts that continue to show bias against women.

Evidence of anti-female biases in science mentoring should still be taken seriously, of course, regardless of implications for understanding numeric representation. This realization raises the question: should diversity initiatives focus more on increasing women’s numeric representation or improving the treatment of women already in these fields?

I don’t have the answer to that question, but these new studies help provide data-informed strategies for tackling these issues.