In times of economic trouble, Spam flies off the shelves. But now, as the economy improves, Hormel Foods’ canned pre-cooked pork is looking for a new, higher-brow market.

The product has played a bit part in ”haute” cuisine since at least 2009, when Vinny Dotolo of the LA eatery Animal paired it with foie gras. In 2011, chef Hooni Kim put it in a stew at his New York restaurant Danji. Last April, Gothamist reported that New York Sushi Ko included Spam fried rice on a $135 tasting menu.

For its part, Hormel seems to be making the most of its newfound foodie hipness, and is looking to capitalize on it with The Spamerican! Tour, launched last week. Hormel tells Quartz that the product’s appearance on restaurant menus inspired the three-month food truck voyage through 12 US cities, which will feature Spam recipes designed by the Food Network’s Sunny Anderson, plus city-specific offerings developed by acclaimed local chefs. San Franciscans can try Robert Lam’s Spammy tots and Chicagoans get Kevin Hickey’s Spam and Jack pretzel sandwich.

Not everybody loves Spam’s latest nostalgic reincarnation. Embracing the ingredient requires ignoring its production process (paywall), which involves the exploitation of immigrant workers, as well as animal cruelty, pollution, and the creation of new food-borne illnesses, says Ted Genoways in his book, The Chain: Farm, Factory, and the Fate of Our Food. ”It’s frankly shocking to see how readily foodies and chefs can disconnect the food from the workers who produce it,” he told Quartz. “To ignore those things is to be fundamentally unconcerned for food and the way food is made.”

Hormel responded to Genoways’ comments by saying that it is “committed to giving employees fair compensation, equal opportunities, a safe work environment and a balance between work and personal life… As part of our commitment to our employees, we have developed industry-leading plant safety practices and a robust training program.”

A food of convenience from the start

Like it or hate it, Spam has been a pantry staple in America and around the world for almost eight decades. During the Great Depression, the gelatinous pork product was first devised by Jay Hormel, the son of the company’s founder, George Hormel, to solve a labor problem: workers’ demands for full-time, year-round work.

“If Hormel was going to pay workers guaranteed wages and promise to make no seasonal layoffs, then Jay Hormel reasoned that those workers should be assigned to tasks previously considered too time-consuming to be cost-effective,” explained Genoways. ”For decades, the company had discarded thousands of pounds of pork shoulder deemed unworthy of the effort it required to cut it off the bone. But now, Jay surmised that the cost of additional wages would be offset if Hormel could simply convince customers to buy that scrap meat.”

Spam was born. The catchy name for the amalgam of pork, salt, water, potato starch, sugar and sodium nitrite was registered as a trademark in 1937, and an all-out marketing campaign soon followed. Teams of young sales executives dubbed “Spam Crews” and a 60-member female performing troupe called “The Hormel Girls” extolled the product all over the country. George Burns and Gracie Allen promoted Spam on their radio show. By 1940, it was eaten in 70% of America’s urban homes.

Spam, spam, spam, spam

It was World War II that gave Spam its biggest advertisement: Hormel contracted with the military to send more than 100 million pounds of Spam to allied troops stationed abroad. Then, as Europe struggled through the post-war shortages of the 1950s, Spam became a mainstay there as well.

In the 1960s, as the US economy improved, Spam lost some of its popularity in mainland America. But in Hawaii and the Asian Pacific, its popularity only grew. After the war, the US government placed sanctions on Hawaiian residents, limiting the Japanese-dominated deep-sea fishing business that had supplied so much of the islands’ protein, Eater’s history of Spam recounts.

Meanwhile, in Korea and Japan, populations were on the brink of starvation. Shipments of Spam became “an absolute godsend,” food historian Rachel Laudan told Eater, and today Korea is the world’s second-largest consumer (paywall) of Spam, after the United States.

By 1970, Spam was part of the international zeitgeist. It showed up in cuisines around the world, and was immortalized in a Monty Python skit in the UK. That year, the company sold its two-billionth can.

Over the next thirty years, sales spiked during recessions when other meat prices went up (the 1970s Middle Eastern oil crisis, the recession of the early 1980s), and also when food scares made other protein sources look risky (the 1990s’ mad cow disease scare, the e. coli breakout at Jack In The Box), Genoways told Quartz.

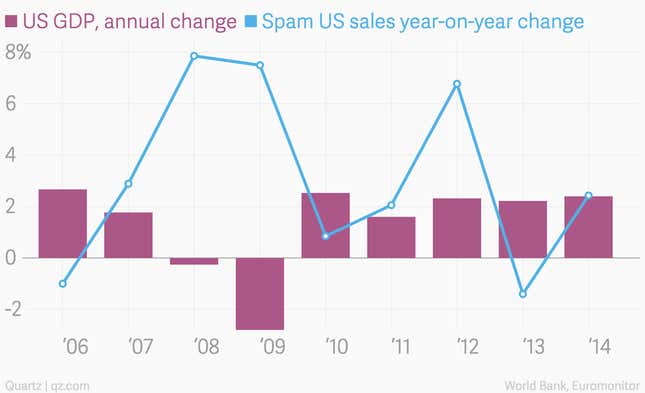

The trend held up through the aughts. In 2008, when the American and global economy was contracting, Hormel sold ever more Spam—a nearly 8% increase over 2007, according to data from Euromonitor.

A new strategy for Spam

Now that the US economy is bouncing back, Hormel is working to make sure that Spam sticks around. While sales dipped in the beginning of 2012 as the economy picked up, the product’s strong international sales ”drove top-line results for the fiscal year 2012,” the company reported.

And lately, even as the the American economy recovers, US Spam sales are again on the rise. In its latest quarterly filing, the company reported improved sales results in the SPAM products despite lower export results.

There are several explanations for this, including high beef prices and persistently stagnant wages. But it doesn’t hurt that Spam has found a new, unexpected foothold in the market, largely thanks to its fans among high-profile chefs.

The LA-based chef Sharon Wang of Sugarbloom Bakery grew up with Spam in Taiwan, telling Quartz that because it was an import, it was ”more of a reward than a day-to-day [food].” In college, though, it became a “go-to product.” She started cooking with it professionally around 2012, and when she stopped, customers complained. Now she’s making her Kimchi SPAM Musubi Puffs for The Spamamerican! Tour. “Culturally and internationally, it’s something we’re familiar with,” she says.

Of course, Spam’s renaissance may just be a passing moment of food nostalgia, and whether or not Hormel can successfully leverage its foodie credibility remains to be seen. But food trends often originate with chefs before working their way into American kitchens. The Spamamerican! Tour looks like Hormel’s attempt to move that process along.