This post originally appeared at First Round Review.

“What could we say that would help you avoid all of the pain, the headaches, the late nights that we had to endure as systems failed and data got corrupted?”

This is how DJ Patil kicked off his session at First Round’s recent CTO Summit. Former VP of product at RelateIQ, and now chief data scientist of the United States, Patil said that 20 minutes was not nearly enough time to sum up all the missteps that yielded transformative lessons for him. On stage with Ruslan Belkin, now VP of engineering at Salesforce by way of RelateIQ, he said their goal would be to share only the most important, most salient mistakes and learnings related to building and launching data products.

That starts with the common mistake that the term “data products” only refers to apps like Twitter or LinkedIn, where social graph is everything. Increasingly, more and more products are falling under this umbrella—including hardware, wearables, and anything else that collects and makes data meaningful for users. To that end, the advice Belkin and Patil have to offer applies to the entire startup ecosystem.

“When you think about data products more broadly, you start to realize that even the dashboards inside your company count. Suddenly your horizons are open, and you can start creating processes that allow you to understand, make, and sell things at scale,” Patil says. So why do so few companies talk about or emphasize building useful data products? To answer this, Patil quotes famed economics professor Dan Ariely:

Truly, it comes down to the fact that building data products at scale is really hard. Here, Belkin and Patil offer a number of insightful tactics that they learned the hard way, so that others can have an easier time and start creating bold, new products that will change the way we see and connect with the world.

Data products need to be built differently

Hacking things together and prototyping may be just as easy with data products as it is with others. But at scale, you run into a bunch of unique challenges. You have to have an arc or plan of progression in mind. They are never one-offs or standalone products. So you can’t just build, test, roll and go, like you might be used to.

You have to start with a very basic idea: Data is super messy, and data cleanup will always be literally 80% of the work. In other words, data is the problem.

“If you take something like LinkedIn in the early days, let’s say, there were 4,000 variations of how people said they worked at IBM—IBM, IBM Research, Software Engineer, all the abbreviations, etc.,” says Patil.

“Trying to clean it up after the fact will take months at least.”

To dodge this predicament, you should build the easy products first—the super simple stuff, the counting exercises, things like collaborative filters, just zeroes and ones. All of these things will become much harder under implementation at scale. “If you try to build crazy ambitious things like machine learning, it’s going to fail on you. Get the pipelines and other stuff correct, then build on top of that.”

Give data back in a powerful way

One of the best examples of this also comes from LinkedIn. It’s the mechanism that shows you who has recently viewed your profile. That’s the kind of information that will drive traffic back to your site and keep it coming back.

“The common mistake here is that you see how giving data back can be great, so you think, ‘Let’s give more! More!’ But adding data to a page is actually inversely proportional to the number of clicks you get,” Patil says.“You have to find the right balance for your audience.”

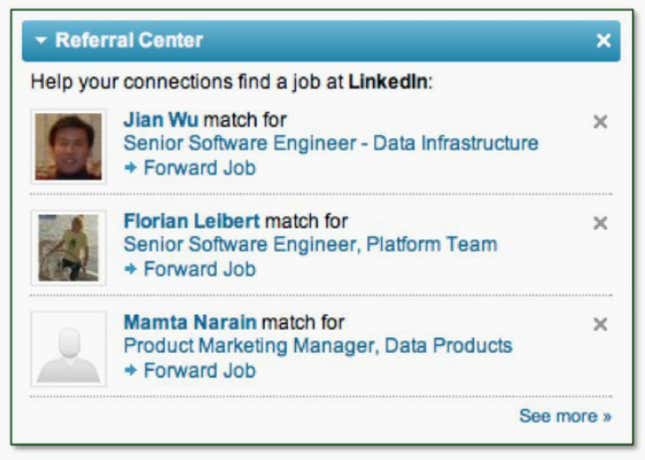

Deciding what data to expose to people isn’t just about how much—it’s about what it says too. One idea Patil and Belkin played around with was marketing jobs to people—like, “Hey, you should apply for this job because it matches your skills!” Soon, they realized this approach was fraught with peril.

“There was too high of a chance that we’d accidentally recommend a more senior person should apply for an internship, or that a confirmed California resident should move to Idaho for work. When stuff like that happens, people get pretty pissed off, and it can mess up your brand pretty fast,” Patil says.“You have to think about what that particular feature will actually be like for a user when he or she sees it. This is where you need to be clever—and when it comes to data products, clever beats smart nine times out of ten.”

The clever solution in this case was to approach job recommendations from a different angle. If “Bill” is the user they are trying to reach, then instead of sending recommended job openings directly to Bill, they decided to send them to his network with the short note: Recommend Bill for this job. It used the exact same algorithm, but with a little twist, it took care of the hard relevancy problems.

“If Bill hears from one of his friends that they think he should take a job, he can still say, ‘Yeah sure man, you’re an asshole,’ but that’s rarer, and the site would never be blamed,” Patil says. “Beyond that, we get to collect all the data that allows use to figure out what’s going on with this feature and make it even better.”

We don’t have time to do it right, but we have time to do it over

This is a favorite saying of Belkin’s, emphasizing the importance of getting things out the door, trying them out, and then iterating once you have more knowledge.

A while ago, LinkedIn built a product called Talent Match. The idea was that a company should be able to post a job opening and get the best recommendations for people who fit the description. It worked awesomely until they tried to scale it and all sorts of complexities emerged.

“It turned out that we had to iterate on all these systems until we were able to understand the right combination of features, the right evaluation framework. Until we got that stuff right, we didn’t know how to build it at scale,” Patil says.

A lot of data products take time to mature and yield the information you need to make them better.

“This can be so hard that even a company like Apple sometimes has to apologize to customers for what was arguably a poor quality data product and recommend competitor applications,” says Belkin. This issue impacts companies of all sizes and skill levels.

At LinkedIn, the “People You May Know” feature started with a big python script on one engineer’s laptop. It wasn’t until 2008, two years after the feature launched, that it started to drive reasonable growth on the platform.

The same thing happened with Twitter Search. It was first launched as a utility for Twitter users. But not until mid-2013 did it become a major driver of traffic and engagement.

Where to start building

A lot of people choose to start building by modeling the product in question. Some start with feature discovery or feature engineering. Others start with building the infrastructure to serve results at scale. But for Belkin, there’s only one right answer and starting point for a data product: Understanding how will you evaluate performance and building evaluation tools.

“Every single company I’ve worked at and talked to has the same problem without a single exception so far—poor data quality, especially tracking data,” he says. “Either there’s incomplete data, missing tracking data, duplicative tracking data.”

To solve this problem, you must invest a ton of time and energy monitoring data quality. You need to monitor and alert as carefully as you monitor site SLAs. You need to treat data quality bugs as more than a first priority. Don’t be afraid to fail a deploy if you detect data quality issues. But there’s one thing you MUST (in all caps) not do, accordingly to Belkin:

“Do not submit to the Apple Store if you have data quality issues,” he says. “You have to make sure you have exactly the right tooling in place, that you have solid schema for all the events you’re tracking, and a schema registry that you can integrate into your development process.”

To reinforce these lessons, Belkin starts his staff meetings with a quick dashboard review. He personally looks at it 20+ times a day, but finds that discussing it actively surfaces problems and the potentiality for problems much faster. As a result, they get addressed faster, before they have a chance to be disastrous.

Product pre-flight checklist

Before you launch a data product live to users, you should work your way through this checklist:

1) The product has to work

Early in his career, Belkin worked at Netscape, and remembers CEO Jim Barksdale—formerly of FedEx—saying, “Look, if you miss delivering 1% of packages every day, in 100 days, a significant customer base will actually be upset.” What you need to consider is how often will users be seeing bad results?

To put it in context of tech consumer products: “Are people okay with porn showing up in their news feeds every three months? Six months? Nine months?” Belkin says. “You have to figure out the levels of what is acceptable.”

How will you deal with embarrassing content and recommendations? This is a real concern that needs your attention. “‘Oops’ moments happen no matter what they do. What will you do? Will you roll back the software in a hurry? Will you try correct something by changing a record in the database on a live production system? By yanking something from the search index? By boosting a ranking again while the system is live? All of that is usually a bad idea. You should have anticipated this eventuality ahead of time and worked out solutions you can immediately deploy.”

2) It has to work for the user

You have to put whatever you’re displaying in front of a user in his or her frame of reference. They have to understand that they’re seeing information because of something concrete—either because they follow a certain user, or they took a certain action, or even perhaps, because they didn’t take an action.

The important thing is that you can’t present data or information that is disconnected from the user’s past experience with your brand or product. No one wants things to happen or appear randomly. Ambiguity will lose users.

A Twitter profile placed in the context of the people you already know who follow the person will make you much more likely to follow them as well, for instance. That’s the clear next action.

3) The user has to feel safe

“This is what I call the Teddy Bear Principle,” says Belkin. “Ask yourself, ‘Will users think your product is creepy or harmful to them in any way?’ It doesn’t have to be, but user perception of these issues can cause long-term damage to your platform.”

First, you have to make sure there’s no possibility of leakage of personally identifiable information. This is no joke. There is always some risk that this could happen due to a flaw in product design or implementation. You may be hacked. Some of your data may not be encrypted or anonymized properly. This is all very serious. You have to do everything in your power to not just prevent this from happening, but convey through good design and solid user experience that you will not let this happen. Users pick up on the smallest of cues to determine whether they should trust a product or not.

4) Users have to feel in control

The way you present user settings—especially as they pertain to privacy—is very important. You need to think of the best way to do this that doesn’t overwhelm people, but present their options clearly, and makes them feel like they have total agency over what they share with who and when. This is often the difference between whether a person ever comes back or not.

5) There are users outside of the US

A surprising number of people don’t realize that the majority of their users live outside of the United States. “In my experience, as many as 35 languages could be relevant to your company. Often data and choices become more limited in different languages. Many users are multi-lingual. You may not be able to deliver the same quality of experience to everyone without a lot of additional effort unless you plan for it,” Belkin says.

Even if you’re at a small startup now that lacks the bandwidth to think about internationalization, these are concerns you need to lay the groundwork to address. You can’t have a huge product entirely in English and suddenly decide it all needs to be in 35+ languages. If you have global aspirations, you have to start layering this in when it still feels premature.

How to organize your team

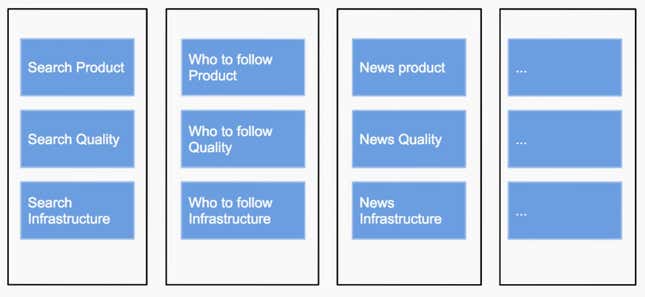

Belkin gets this question all the time: How do you organize your product and engineering teams in situations when you’re building and iterating more than one product at a time? What’s the right configuration of people?

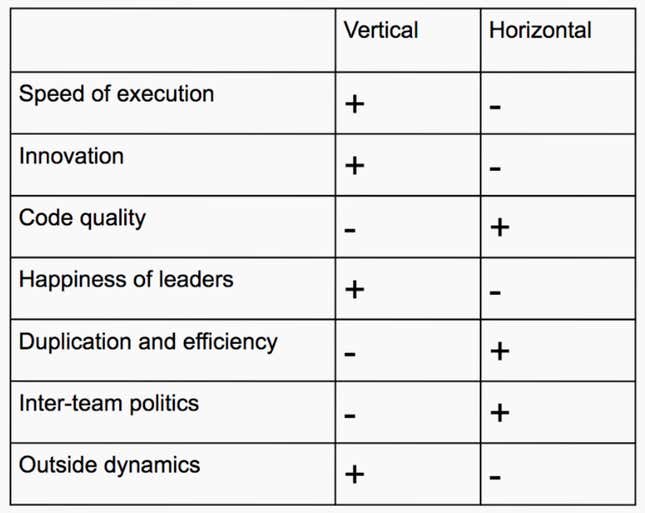

“This brings up an age old debate: Should you go vertical or horizontal?” What’s the right answer?

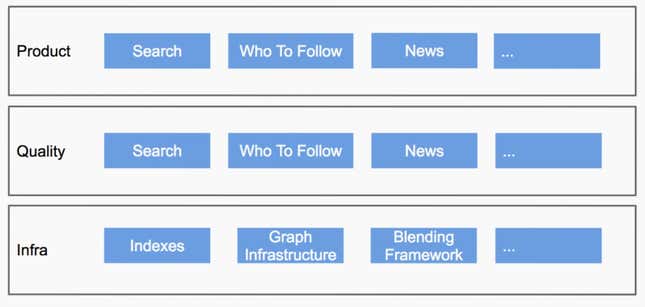

“There isn’t a generic right answer, but there is a right answer for the stage of company you’re at,” says Belkin.“I like to think about it in the form of a feature matrix, like this:”

“Evaluate what you’re doing along these dimensions—how important is speed of execution, innovation, code quality, user happiness? What kind of inter-team dynamics need to work for the product to get built and scaled?”

Generally speaking, vertically-integrated teams win when it comes to speed of execution or innovation. People are happier and external relationships are better simply because the team is more aligned with business objectives.

Horizontal teams normally produce higher quality output. They are more efficient and generally are better at inter-team dynamics.

The real key is to keep experimenting and iterating not just with products, but how you build them as well. You aren’t going to solve the way you work all at once. New data will be revealed that you can channel back into your process. Don’t expect to nail it out of the shoot—and especially don’t expect the same level of ease to continue as your audience and company grow.

“There’s a great metaphor for building data products,” Belkin says. “It’s a lot like climbing a mountain. Many have come before you, many will come after you. There are some paths not yet traveled, but if you keep your eye on the summit and take small steps, you’re sure to get there.”