From the road, the bright sun glinting off the white marquees gives the refuge camp in Johannesburg a falsely festive feel, at odds with the desperate stories of the immigrants sheltering here. Police guard the gated entrance. It is eerily quiet. According to Gift of the Givers’ project manager, Emily Tomas, many of the refugees are still going to work in the city, returning when the sun goes down.

Some, however, choose to remain in the safety of the camp. As the brutal murder of Mozambican Emmanuel Sithole on Saturday demonstrated, even daylight is not a guarantee of safety.

Inside the men’s marquee, a waterproof ground covering is covered with blankets and a few mattresses, and the one or two suitcases belonging to those lucky enough to have salvaged some belongings. A group of about ten men, all of them young, are huddled together on the ground. Save one, who vacated his home in Johannesburg that morning, they all arrived here from Kwa Zulu Natal, where South Africa’s recent xenophobic attacks against poorer immigrants have been concentrated.

Twenty-four year old Aarav*, from Malawi, was at work last week when his brother called to tell him that his house was on fire.

“My brother phoned. He said, your home, it is burning,” Aarav mimed pouring fuel and striking a match. “I never go back that side. We running away.” For three days, they hid under a bridge, before fleeing to Johannesburg.

The man next to him, wearing a South African t-shirt, carefully set a bowl of soup down on the tarpaulin between his legs. Donations received by Gift of the Givers have ensured that the refugees here do not go hungry. In between mouthfuls, he explained how he had come to South Africa three months ago to build a life for himself. Now he was leaving everything behind.

“I cannot lose my life for money.” He laughed without humour, shaking his head, disbelief still raw in his eyes. “I will not come back here. Never, never, never.”

“[In Johannesburg] I met with the criminal people,” another of the group, Luke*, spoke up in a soft voice. “They stolen from me my money and my passport.” Luke has a wife and two children back home in Malawi, anxiously awaiting his safe return. “After that I think that it’s better to go home. I just want to go home.”

“I just want to go home”: the phrase was repeated over and over, passed around the tent like a prayer.

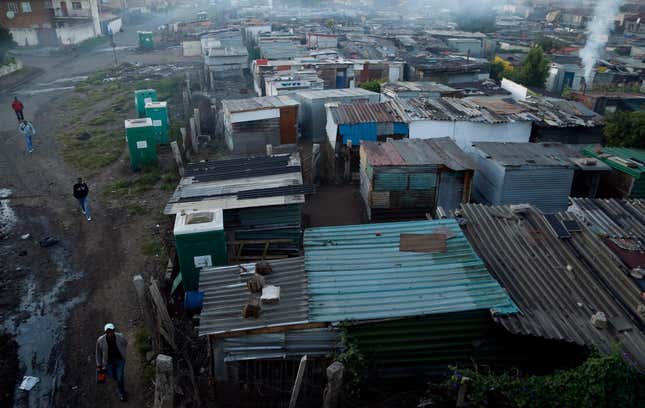

Since the beginning of the most recent spate of xenophobic attacks three weeks ago, at least seven people have been killed. Thousands of immigrants have fled their communities, hounded by locals who maintain that their presence here is adding to the already considerable woes of South Africa’s poor. President Jacob Zuma condemned the attacks and the government has finally deployed the army to xenophobic hotspots including Alexandria in Johannesburg where Sithole was killed.

The refugees who have ended up here at the Gift of the Givers camp are comparatively lucky: the camp, erected last week, shelters only around 40 people. Phoenix, the largest camp in Durban, has swelled to 2, 400 people in the last few days. While bus-fulls of Zimbabweans, Malawians, Nigerians and others leave the country, NGO groups, including is Doctors Without Borders, are struggling to meet their growing medical and humanitarian needs of those left behind.

Yet while heavy police and military presence might help to dampen the blood lust of frustrated locals, the underlying drivers—poverty, joblessness and hopelessness — remain. Having witnessed their lives going up in smoke, these immigrants are not waiting around for these grievances to be addressed and for South Africa’s misplaced anger to dissipate.

For them, the South African government’s response has been too little, too late.

Outside the marquee in the Gift of the Givers Camp, a small child with a contagious grin plays with a beach ball. He is too young to understand the violence. Trustingly, he runs from adult to adult, his open friendliness the antithesis of the sentiment that brought him here.

(*not their real names)