“Vanity capital” is the new metric for narcissism, and analysts say its value worldwide is greater than Germany’s GDP

Last month, Bank of America Merrill Lynch released the compellingly titled report, “Vanity Capital: The global bull market in narcissism,” which put a price tag on the amount we spend globally on products and services that enhance our appearance or prestige. That price tag is huge: $4.5 trillion, according to the report—larger than the fourth largest economy in the world, Germany, with its GDP of $3.7 trillion—and still growing.

Last month, Bank of America Merrill Lynch released the compellingly titled report, “Vanity Capital: The global bull market in narcissism,” which put a price tag on the amount we spend globally on products and services that enhance our appearance or prestige. That price tag is huge: $4.5 trillion, according to the report—larger than the fourth largest economy in the world, Germany, with its GDP of $3.7 trillion—and still growing.

The immediate question the report raises is whether it’s even possible to measure such a thing. The premise—to quantify the dollar value of all purchases worldwide motivated in some way by vanity—is a little nutty at its foundation. The authors define “vanity capital” in terms that sound like Gordon Gekko and Abraham Maslow got together to deliver a self-help seminar: It’s ”the pursuit of, and the accumulation of, attributes and accessories to augment self-confidence by enhancing one’s appearance and prestige. It is self-actualization through self-improvement and self-focus.”

On top of that, the process of separating vanity from non-vanity purchases is a rather subjective one. Some of the goods and services categorized as vanity capital seem fair enough: jewelry, art, a private jet, or basically anything you’d see on Rich Kids of Instagram.

But is your smartphone a vanity spend, or a practical necessity? Do you wear a wedding ring to enhance your appearance or prestige? As for spending on services instead of products: Sure, a getting botox treatment is somewhat vain, but what about pursuing an Ivy League education?

And the report includes middle-market products too, such as makeup, fitness wear, and health supplements. In fact, the non-luxury category makes up the vast bulk of the vanity-capital market—90% according to the report. Quartz has reached out to Bank of America Merrill Lynch for comment and will update with any response.

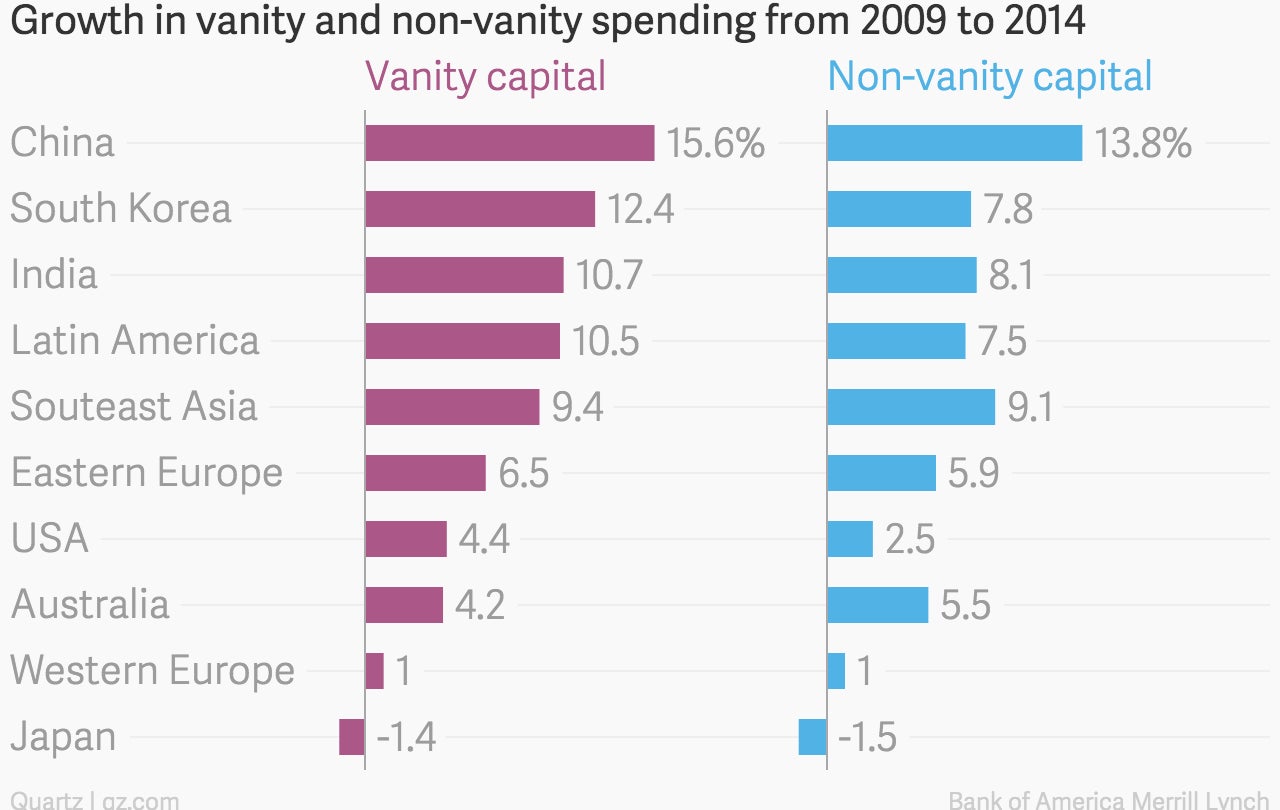

Still the report does raise some intriguing points—and just the fact that Bank of America Merrill Lynch, one of the largest banks in the US, would try to quantify the size of worldwide vanity spending indicates that this is a market worth watching. The report’s calculations offer a compelling argument for why: “It is one of the most durable growth stories in emerging (and developed markets),” it states, and it’s apparently growing much faster than “non-vanity” spending.

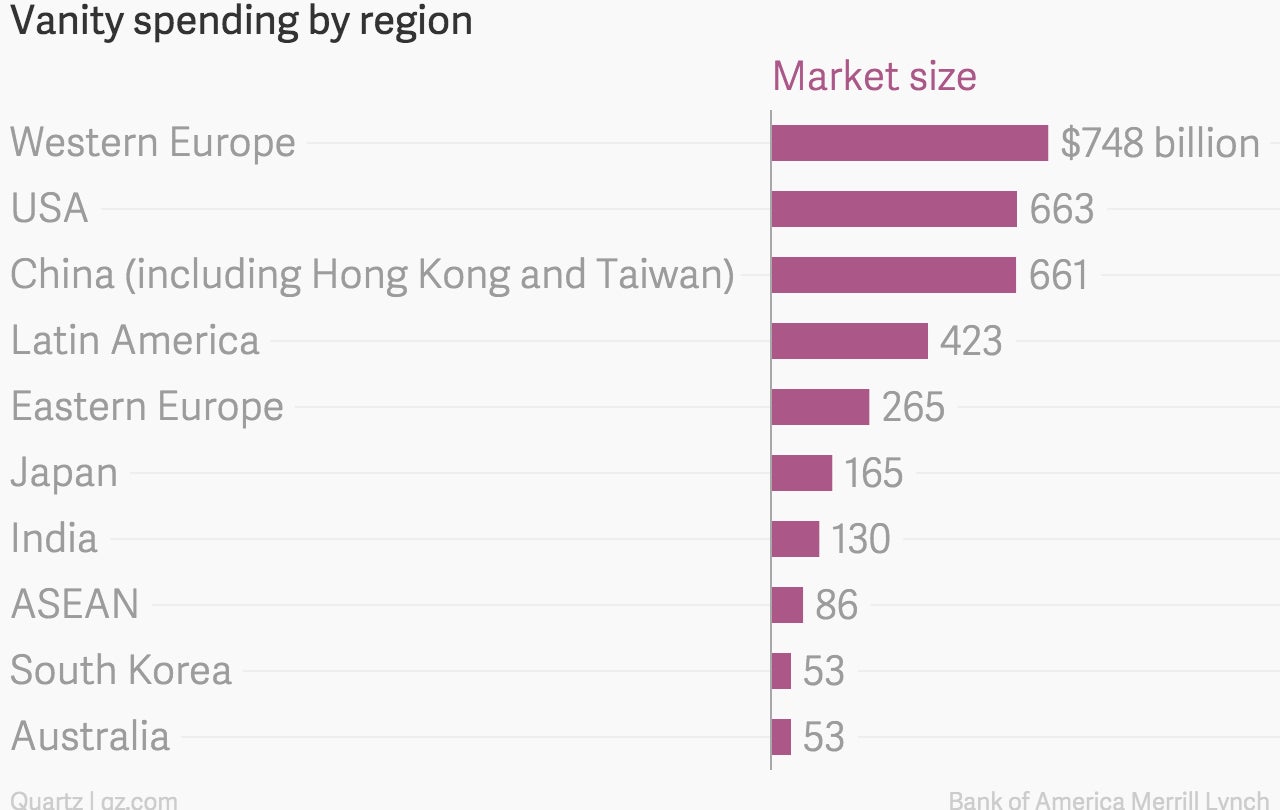

The report attributes this to the growth of per-capita income in developing economies. China, as Quartz has reported, is the world’s fastest-growing market for this sort of vanity spending, driven by consumers eager to publicly display their new economic status (pdf).

Although, in absolute numbers, Western Europe still leads in vanity spending for the moment.

The global market for vanity capital continues to grow, according to the report, in part because of the improving economic standing of women around the world, which allows them to buy more stuff. The changing shopping habits of men are also a factor: “‘Man-bags’ are actually a thing now,” it notes. (Actually, they’re more than just a “thing.” They’re big business.)

The analysts also cited the spread of social media, which “makes narcissism and envy ubiquitous;” e-commerce, which allows people more shopping options than ever; and “rebellious consumption,” in which coming off as cool replaces traditional class signifiers, i.e. looking wealthy.

Of course among the many reasons people shop is a psychological longing for status. We buy things that make us somehow feel we are better—more attractive, more powerful—and that show the outside world that we’re good enough, smart enough, and people like us.

Scott Galloway, a professor of marketing at NYU’s Stern School of Business, goes a step further, saying the cachet that all vanity capital carries is distinctly libidinous.

“Men want to spread their seed to the four corners of the world,” he says, and women want their choice of mate. Anything that projects prestige or increases our physical attractiveness helps us accomplish those goals.

It all comes off as a bit primitive and reductive, and Galloway admits it sounds base. On the other hand, status does play a significant role in the reproductive habits of our close primate relative, the chimpanzee. There’s also research to suggest that evolution has built the desire for social status is into human psychology, and part of that includes using material objects to signal our prestige (pdf).

Whether $4.5 trillion is an accurate measure of how much people spend on purchases motivated in some way by vanity is debatable. But in the age of the selfie, it seems a safe bet that the number, whatever it may be, is growing.