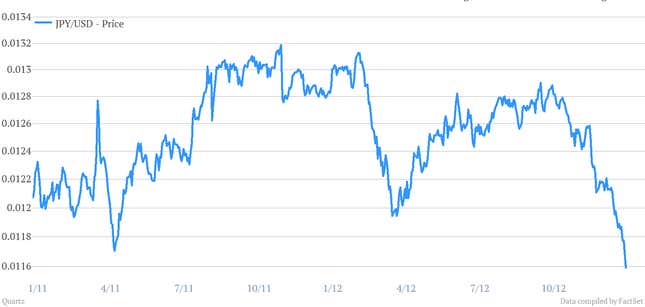

Japan’s plan to devalue its currency is in full effect, with the yen reaching its lowest value versus the dollar in two years. While there’s a host of external reasons for its decline against other major currencies, the main one is the clear expectations set by the country’s policymakers, led by new Prime Minister Shinzo Abe: We are tired of tolerating a slow-growing, deflationary economy, and we’re going to ease our way out of it.

Abe is not solely responsible, though. The yen’s downward movement began in September, after the Bank of Japan expanded its bond purchasing program, increasing the quantity and extending the time-frame. The next week, on Sept. 26, the bank’s deputy governor delivered a speech entitled “Economic Slowdown and Monetary Easing” explaining the decision (emphasis mine):

As for the question on what cases the Bank will make policy responses in, I myself mentioned at various opportunities that “when the outlook turns out to be weaker than expected or the risk associated with it intensifies, the Bank will not hesitate to implement additional monetary easing.” … As a result of such examination at the latest Meeting, the Bank judged that the scenario it assumed had been delayed or weaker than expected. As long as there is such judgment, there is no reason to procrastinate a policy response.

That was the beginning of the end for Japan’s economic complacency. In November, the government announced the snap elections that many expected to bring Abe into office. When he was elected in December, he made explicit his willingness to change the law to force the bank to raise its inflation target, and began putting in place a new fiscal stimulus plan.

Tim Duy, an Oregon University economist who once monitored the activities of central banks around the world for the US Treasury, writes that a higher inflation target is only part of the picture: the government of Japan appears poised to activate a so-called “helicopter drop”—a tactic discussed by the US Federal Reserve’s Ben Bernanke, whereby a government kick-starts the economy by spending money that created by the central bank. Since this requires the government and the bank to work hand-in-hand it is, says Duy, potentially historic, “[a] story of a modern central bank stripped of its independence. Of a modern central bank forced to explicitly monetize deficit spending.”

That’s the kind of thinking that has hedge funds shorting the yen, looking to make a killing after yet another year of losing out to humble index funds. A yen that’s cheaper relative to other currencies could be a boon to speculators, but the goal is to help improve Japan’s export sector and repair its current account deficit.

Japan is trying to take its destiny in its own hands: Duy has argued that Japan’s only escape from its massive debt load, deflation and slow growth is this kind of stimulus. It may risk more inflation than Japan is bargaining for, but that’s the least-worst way to escape its economic conundrum. And if that sounds extreme, well, Duy thinks the same medicine might be coming to the United States and Europe down the line.