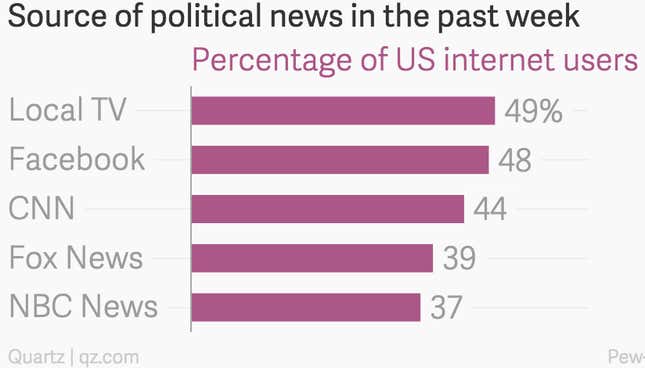

When nearly half of US internet users are getting their political news from Facebook, it rightfully raises many worries. Chief among them is that Facebook’s powerful algorithm creates a “filter bubble” in which users mainly see posts they agree with, reinforcing the heavily polarized nature of American political discourse.

In research recently published in Science, researchers from Facebook and the University of Michigan suggest that the news feed algorithm is less influential than some people have made it out to be. Instead, they claim it is mostly users themselves who, through their decisions about what to click on or who to be friends with, are responsible for the creation of any ideological bubbles.

Don’t be so quick to let Facebook off the hook, though. Despite being published in a reputable science journal, the researchers’ conclusion appears to be questionable.

What did they do?

The researchers chose a sample of 10 million US-based Facebook users and analyzed the news stories they were exposed to, or interacted with, on the site. The links to news stories that the users had shared were sorted into two categories: hard (for national news, politics, and world affairs, for example) and soft (for topics like sports, entertainment, and travel).

Some 13% of the links in the newsfeed were in the hard news category. Those posts were then classified as being “liberal” or “conservative,” based on the political affiliations of at least 20 people who had shared the story (affiliations were determined by the political leanings declared on the users’ profiles) and based on the Facebook post’s content (not the content of the story itself).

Then the researchers added a layer of data showing how many of the posts actually made it to the feeds of these users’ friends and how many people clicked through. In the final step, they analyzed how much “cross-cutting” content—content with the opposite political bent of a given user—people actually saw and engaged with.

What did they find?

In short:

If there were no algorithms, and each user’s newsfeed were assigned random posts, then 45% of the stories liberals would be exposed to would be cross-cutting, that is from the bucket of stories classified as conservative. For conservatives, cross-cutting content would account of 40% of the stories in the feed.

Layering in the stories shared by friends, there is a drastic difference in how much cross-cutting content a user would see. The newsfeed algorithm further reduces cross-cutting content by about 1.5% for liberals and 1% for conservatives, and then people’s own choice on what content to click on causes a further reduction by about 1% for liberals and 4% for conservatives.

Given these findings, the researchers argue that overall, the newsfeed algorithm does less of the “wrong” filtering than you and your friends do when choosing which stories to share or to click on. They write, “We conclusively establish that on average in the context of Facebook, individual choice more than algorithms limit exposure to attitude-challenging content.”

What are the problems?

For starters, there’s the sample used in the study. To draw results at this scale without individually interviewing the subjects, the researchers relied on Facebook users who self-report their political affiliation, have clicked on a hard news story at least once in the last week, have logged in at least four days a week, and are 18 years and older. But this pool of users isn’t very representative of Facebook users in general. In a Microsoft Research blog post criticizing the Facebook study, the University of Michigan’s Christian Sandvig (he is not the University of Michigan researcher affiliated with the study) writes:

Who reports their ideological affiliation on their profile? It turns out that only 9% of Facebook users do that. Of those that report an affiliation, only 46% reported an affiliation in a way that was “interpretable.” That means this is a study about the 4% of Facebook users unusual enough to want to tell people their political affiliation on the profile page. That is a rare behavior.

As Sandvig argues, “We would expect that a small minority who publicly identifies an interpretable political orientation to be very likely to behave quite differently than the average person with respect to consuming ideological political news.”

Eytan Bakshi, the lead Facebook researcher on the study, admits this is indeed a limitation, just as the samples used in other kinds of studies have limitations. “We chose the complete subpopulation of users for which we could answer our question,” he tells Quartz.

But then there are the problems of the Facebook algorithm itself, the most damning of which is that because Facebook won’t divulge exactly how the algorithm works, it is impossible to independently verify the claims the study makes about it. Another issue is that, as the researchers explain, the newsfeed algorithm tweaks things based on many factors—including the choices that individuals make. It is unclear, then, how the researchers can separate out the impact of the algorithm from the impact of personal choices made by users or their friends.

So we’re taking Facebook’s conclusions with a large grain of salt. But we give the company credit for something: this level of data analysis of people’s habits would not have been possible in the pre-Facebook world.