Last week, Togo, a country of 3.5 million people, voted for incumbent president Faure Gnassingbé for a third time. Gnassingbé is the son and immediate successor of Togo’s fifth president—Gnassingbé Eyadema—and, once he serves out his third term, his family will have run Togo for 48 years.

In light of this latest development and as the continent moves toward more closely contested elections, it might be time to quickly reflect upon the current status and trends of family political dynasties in sub-Saharan Africa. The first question is: Is Africa different from the rest of the world?

Political dynasties exist around the world. In the United States in 2001, George W. Bush became the first modern president whose father (president George H.W. Bush) had also been elected president. (The sixth president, John Quincy Adams, served from 1825-1829 and was the son of the second president, John Adams.) Bush also became the first U.S. president to hold the position for longer than his father.

In East and South Asia, there have been many daughters of heads of state who have been elected to the same position, such as South Korean president Pak Geunhye, former Philippines president Corazon Aquino and former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. In Pakistan, in a rare occurrence, a husband took over from his wife, Benazir Bhutto. Clearly, we should be wary of characterizing political dynasties as an African phenomenon. However, given the vastly maledominated world of African politics, what do we know about African fatherson presidential transitions and legacies?

Succession: By birth or competition

The experiences of the U.S., the Philippines, and South Korea seem to indicate that citizens are willing, through a contested process and based on an individual’s merit, to elect family members of former heads of state. Notably, in cases like these, usually the family members do not immediately follow their parent; there is a time lag between the two.

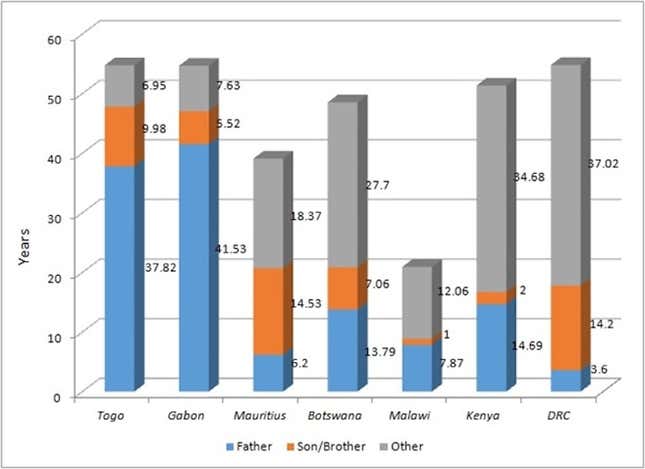

Africa has a more mixed experience. Seven countries on the continent have had both father and son (and one brother) lead the country: Botswana, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Gabon, Togo, Mauritius, and Malawi (Morocco and Swaziland are excluded from the list since they are kingdoms). In each of these cases, the succession process has been different, as has the interim between father and son.

Three sons of a founding father (the first president or prime minister after independence) are currently in power in Botswana, Kenya, and Mauritius—president Ian Khama, President Uhuru Kenyatta, and Prime Minister Navin Ramgoolam, respectively. In the case of all three, the succession took place over a decade after the father left office: In Botswana, Khama was elected 27 years after his father left office, while in Kenya, Kenyatta was elected 34 years after his father, and, in Mauritius, Ramgoolam was elected 13 years after his father. Therefore, enough time had elapsed in which citizens could assess the impact and results of the father’s leadership and make an informed decision regarding the son.

By the time the sons became president, the three countries had a history of contested elections, and each one took over in generally peaceful elections and under stable constitutions. Malawi’s president Peter Mutharika similarly was elected president years after his brother’s death in office.

On the other hand, some sub-Saharan countries have experienced immediate succession by the son of the head of state after his father’s death, often leading to decades of rule by a single family. With president Gnassingbé’s reelection, his family will have run Togo for over 87% of its 55-year post-independence history, with five more years to go. Gabon has a similar experience: With a father and son at the head of the country for over 86 percent of the country’s post-independence history (1967-2009 and 2009-2015)—47 years out of almost 55 years—and the son is still in power.

In the DRC, president Joseph Kabila came to power in 2001 immediately following the untimely assassination of his father. Altogether, the Kabilas have ruled the DRC for a third of the country’s post-independence history—almost 18 years.

The Rangoolam family of Mauritius has similarly ruled the country for over half of its independence history, for 20 out of 39 years. However, as noted above, succession was not immediate from father to son but rather through a contested process with two leaders in between.

Figure 1. African political dynasty’s years in power, by country

So, given the mixed experiences of these African countries, can we identify a trend on the continent? The automatic succession of sons does not seem to be the norm. There have been over 38 cases on the continent where the leader passed away in office, and sons have succeeded their fathers in only three. Over the last two years there have, however, been two contested elections that involved the son and brother of a former president—Kenyatta in 2013 and Mutharika in 2014.

Increasingly, countries have put in place constitutional provisions to handle the passing of the president or are respecting constitutional provisions from earlier constitutions such as in Nigeria, Ghana, Zambia, and Ethiopia, all countries who have seen their presidents pass away and whose transitions have been handled in a smooth and constitutional way. It seems that the passing of presidents has not generated prolonged political instability on the continent.

Africa does not have a monopoly on family political dynasties. However, to guard against the creation of birth-right dynasties as opposed to merit-based family political dynasties, recent events suggest that countries should and must have clear constitutional processes for succession as well as open transparent freely contested elections. In Kenya, Mauritius, and Botswana where this has happened, the sons of past leaders are trying to keep the memory of a past not yet forgotten alive. History will determine which sons carry the day and how Africa’s president’s sons are treated in the future.

This piece was originally published on the Brookings Institution’s Africa Growth Initiative blog, Africa in Focus, and can be found here