After falling roughly 60% from July through March, oil prices are now up around 44% from their bottom. The chatter among many investors and industry players is that the worst is over. The only questions remaining, they say, are how high prices will go from here and how soon oil drillers can resume counting their profits.

Others suggest that the market is getting giddy—oil prices will turn back down, they counter, namely because the conditions that produced the breathtaking plunge over the last 11 months largely still persist. The recent rebound is “likely a false dawn, I’m afraid,” Jamie Webster, an analyst with IHS CERA, tells Quartz.

No one knows with certainty what the “correct” oil price is. But contrarians like Webster make a persuasive case that the bulls are getting ahead of themselves—and their argument suggests we’re probably headed for another oil price rout. If we are, then it’s good news for those living in heavy oil-consuming nations such as Turkey, Pakistan, most of Europe, and the United States. It’s more gloom for petro-states like Iran, Nigeria, Russia, and Saudi Arabia.

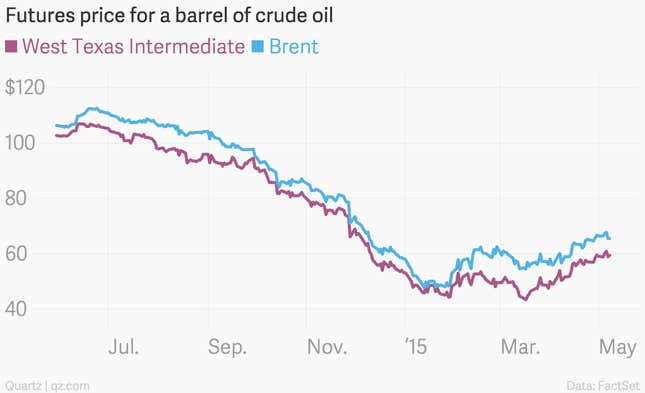

This chart shows how prices have tracked since last summer: a deep plunge, followed by a spike in April, and a continued, steady rise since.

The reasons for the current spike? Production of US shale oil seems to be leveling off, violence in Libya and Yemen continues to shake confidence in the Middle East, and demand appears to be growing, all of it adding up to a far tighter market. Prices are now nearing the point—$60 a barrel and higher for US-traded benchmark West Texas Intermediate—at which aggressive drillers say they can earn a terrific profit.

And the party won’t stop there, say the bulls at Bernstein Research. In a May 5 note to clients, they predict that prices will soar another 25% next year, to $85 a barrel.

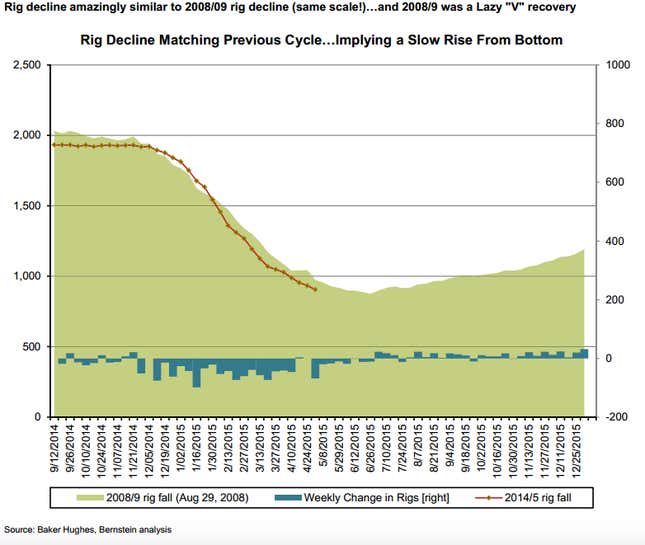

One point raised by bears is that hundreds of partially drilled wells are sitting idle in the US shale oil fields; and once prices firm up at around $65 a barrel, producers will resume their work on the wells, refilling the gusher of oil into the market. But Bernstein says drilling is not a linear activity—history, its analysts note, shows that when drilling halts in an oilfield bust, it comes back in a far slower ramp-up. Its chart below examines the 2008 oil bust.

US production growth is slowing for sure, but shale oil output is still going to be higher, not lower, than last year. According to the US Energy Information Administration, US production will grow by 710,000 barrels a day this year. As for oil in storage, it’s true that the single-week figure last week was almost 5 million barrels lower than expected, a fact that pushed up prices this week. But US oil storage remains at an 80-year high—at 487 million barrels.

The recent drop in storage may ultimately be entirely technical. Paul Sankey, an analyst with Wolfe Research, said that the decline may simply reflect refiners turning it into products such as fuel and lubricants. In a note to clients, Citi said that when you tally up both the storage of crude oil and products, you get an increase of 6.6 million barrels last week, to 1.25 billion barrels, which is 166 millions barrels higher than last year at this time, and 140 million barrels above the five-year average.

In any case, the United States is only part of the oil glut story. Saudi Arabia is pumping 10.3 million barrels a day, its historical peak. The United Arab Emirates, too, is at a peak—2.9 million barrels a day, with plans to raise that to 3.5 million in 2017. Kuwait is pumping 2.8 million barrels a day, a 42-year high, and aims to be producing 4 million daily in 2020. Russia is producing a whopping 10.7 million barrels a day, a post-Soviet high.

If there is a nuclear deal with Iran, the situation may spiral out of control as Tehran attempts to market some 30 million barrels of oil floating in its own storage ships. In fact, a huge surplus of unsold oil is tooling around the seas looking for buyers. It includes millions of barrels of oil from Azerbaijan and Norway, and a whopping 80 million barrels from Nigeria and Angola.

Drillers aren’t really suffering, contrarians say, because they have hedged their production. They will continue to produce oil through the year because the hedges protect them from extreme losses.

How low could prices fall? Bank of America Merrill Lynch is betting on $50 a barrel. Stephen Schork, a respected derivatives analyst, told Marketwatch columnist Howard Gold that WTI could overshoot this year’s lows of about $40 a barrel and plunge all the way into the $30s.