The word “artisanal” gets thrown around a lot these days, but sometimes the term is warranted. Consider the work of the Austrian fashion designer Carol Christian Poell. He dips the kangaroo-leather sneakers he creates in latex and hang-dries them, freezing the latex in perpetual drip, and he places titanium inserts in the split elbows of his jackets, like prosthetic armor. These pieces come together by hand in limited quantities, and people—primarily men—pay handsomely for them: His most stratospherically priced leather jackets can reach $8,000.

In the past few years, a small group of ultra-niche high-end designers with a thing for black clothes and intricate, artisanal production techniques has gradually risen to prominence in fashion circles. The labels in this group include Carol Christian Poell, Boris Bidjan Saberi, Guidi, A1923, Label Under Construction, and Ma+ (you say it “M-A-cross”), as well as a handful of followers, such as newcomer Leon Emanuel Blanck.

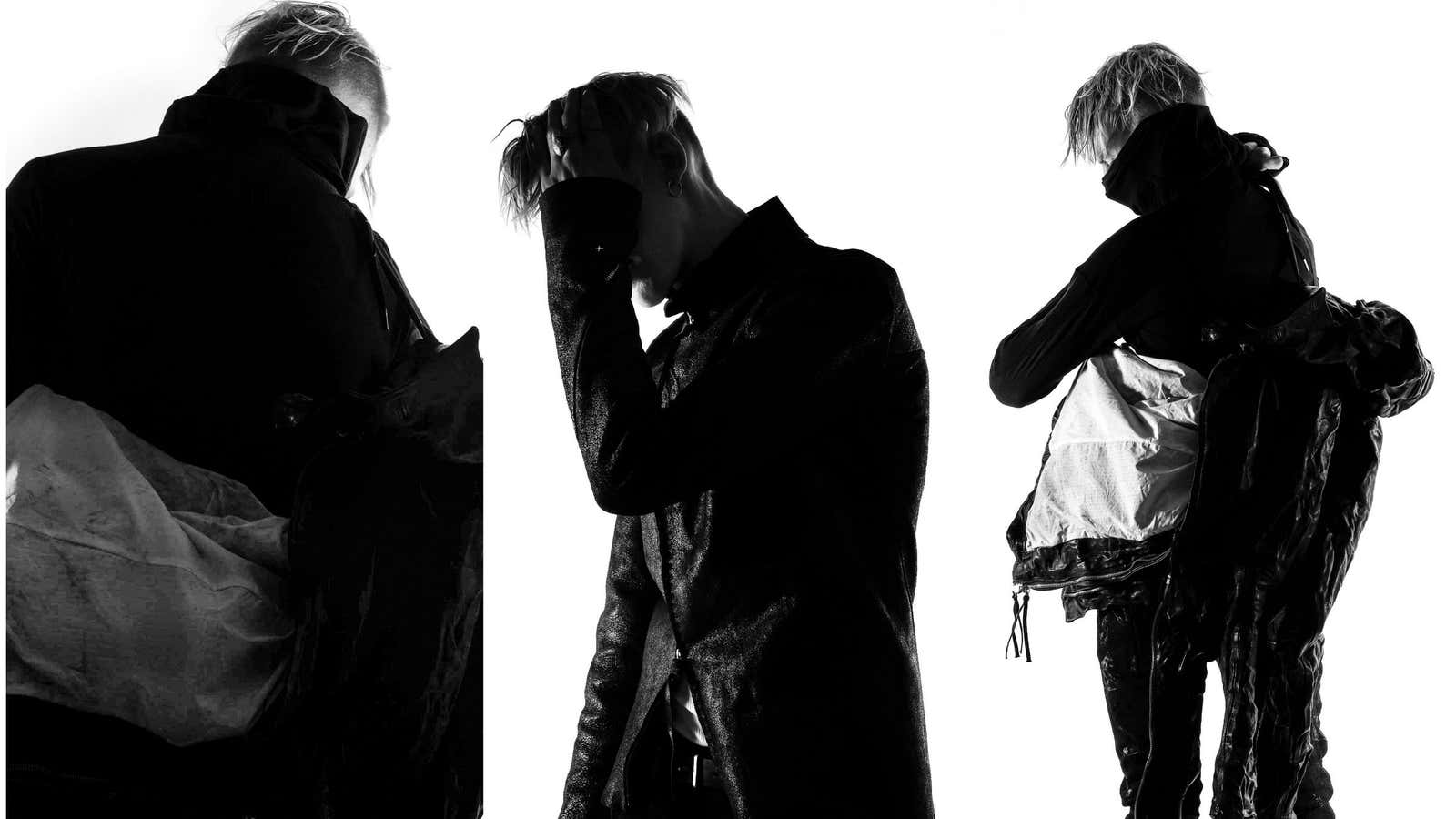

What these designers make are hand-crafted luxury goods, but darker, harder, and meaner than what most people think of as luxury—call it dystopian luxury. Their garments look a bit like costume design for Mad Max: mostly black, distressed, vaguely primitive in their construction. But the textiles, even when they’re tough and course, are extravagant and unique. A suit by Poell on display in the exhibit ”What is Luxury?” at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum is made of a specially developed fabric containing glass beads.

The prices are also decidedly at the luxury end of the spectrum: At retail, jeans commonly approach $1,000 or more.

You won’t see their work in magazines or mainstream fashion outlets. Most of these designers deliberately avoid that sort of exposure, shunning runway shows and publicity, with the exception of Saberi, who presents his collections in Paris. But among guys who obsess about clothing, and particularly on the internet’s under-the-radar fashion forums, their work is highly coveted for its craftsmanship and dark, aggressive design.

Black and treated leather

“It comes down to two things: black and treated leather—it’s that simple,” says Karlo Steel, founder of New York shop Atelier, an avant-garde fashion institution which first opened in 2002 (and was recently rebooted under new ownership). Atelier’s first two accounts were Poell and Carpe Diem, the Italian cult label whose designers splintered off to create Ma+, Label Under Construction, and A1923 after Carpe shuttered in the mid-2000s.

The leather skews toward heavy, rugged hides, such as horse. Much of it comes from the Italian tannery and shoemaker Guidi, known for the exceptional quality of its skins, which include calf, donkey, kangaroo, and bison.

Steel compares the look to Marlon Brando in a t-shirt, jeans, and biker jacket in The Wild One. “It’s a much more designed version of what really goes back to the 1950s, but with a roughness that has a really masculine appeal,” he explains. Now, the t-shirt looks liquid and elongated, the jeans are black and waxed, and the jacket resembles a blackened skin that’s been lacquered and abused.

Saberi is known to break in the leather jackets his label crafts by wetting and then wearing them himself to mold them to his anatomical form.

The clothes draw on other reference points, too. Poell experiments a great deal with suiting and tailored wear—sharp-shouldered, impeccably cut blazers are one of his signatures—and Label Under Construction specializes in knitwear. Many of the designers borrow from East Asian and Middle Eastern garments, as well as hip-hop. They make use of draping, asymmetry, and high funnel necks, as well as the occasional colored leather (blood red, for instance).

Broadly, the clothes are menacing and macho. “The guys into Carol Christian Poell are not into prissy,” Steel says. “They’re into motor oil.” Footwear by A1923 comes in boxes labeled “Do not handle with care.”

A growing market

Those guys include some celebrity clients, such as the actors Brad Pitt and Jude Law, and a growing number of men, as well as some women, around the world. In addition to Atelier in New York, the retail shops Vertice in London and Darklands in Berlin also tell Quartz they’ve seen increased demand for these brands in the last four or five years.

Vertice says demand has accelerated most in the last year and a half, and sales of Saberi’s clothes in particular have increased 30% each season. Poell’s clothes and shoes by Guidi are also popular.

The growth in the market is noticeable online too, in the discussion threads on prominent menswear forums, such as Styleforum and StyleZeitgeist, which revolves almost exclusively around these designers. Rising resale hub Grailed teems with their clothes, and luxury menswear site Mr. Porter even carries Guidi now.

Campbell McDougall, the owner of Darklands, and Zika Liu, the buyer at Vertice, both tell Quartz that it’s the quality and exclusivity of the clothes that attract new customers. Everything is thought through, from the zippers to the stitching.

And it’s quite elaborate stitching. A common detail is overlock stitching—a loose, open stitch visible on the surface of the clothing—that calls attention to the construction of the garment, and perhaps as importantly, resembles sutures holding a wound shut. Leopold Bossert, one of the newer talents working in this aesthetic, uses modified mid-century sewing machines originally designed for use on heavy upholstery to get unique stitch types, such as an adjusted overlock that morphs into a normal closed stitch.

Given the meticulous workmanship, the clothes are extremely expensive, and to appreciate them requires the sort of esoteric knowledge and obsession that men often lavish on cars or high-end watches.

For many of the customers, the high barrier to entry, in terms of dollars and comprehension, is part of the appeal. They let the wearer identify himself as an insider, a committed adherent of the group’s aesthetic.

In their experience, Steel and McDougall say, this exclusivity has a powerful psychological draw. People buying these clothes define themselves in opposition to the prevailing fashion system.

Liu goes a step further, saying customers want “self-appreciation, to feel more confident and differentiate themselves from the rest of people. Basically, to make themselves feel superior.”