For some time now, Greece’s cash-strapped government has been seizing the reserves of municipalities, pension funds, and other state bodies to settle its debts and pay other expenses. Earlier this week, it repaid an IMF loan with money it kept on deposit at the IMF itself. All the while, the Greek government has made only halting progress with its lenders—chiefly other euro zone countries—in unlocking billions of euros in crucial bailout funds in return for deeper economic reforms.

This has been the story ever since a new government was elected in Athens in January. But things are now truly coming to a head, it seems, with Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis (pictured above) saying that the country only has enough cash to last for “a couple of weeks.” Signing a deal with creditors to release the €7.2 billion ($8.2 billion) Greece is owed as part of a previous bailout, which expires next month, is “terribly urgent,” Varoufakis said.

Each day of delay on a new deal brings Greece closer to default. If it missed a bond or loan repayment, it could set off a chain of events that leads to its ejection from the euro zone. Before that happens, it would probably impose capital controls, stemming the flow of money from the country if—or when—things took a sharp turn for the worse.

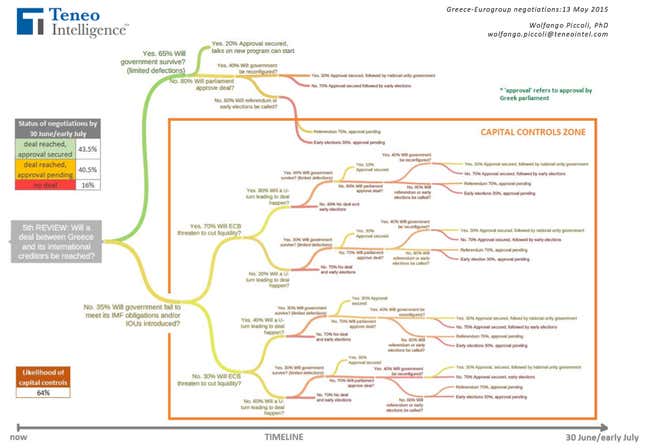

Wolfango Piccoli, an analyst at Teneo Intelligence, a research firm, thinks that capital controls are now more likely than not. That’s because although an eleventh-hour deal with creditors is likely, prime minister Alexis Tsipras will find it hard to win the necessary votes from an austerity-weary parliament—a national referendum on reforms (or even a snap election) may be the only way to break the deadlock, in effect taking the decision out of recalcitrant ministers’ hands.

“What pleases the international institutions increases the chances of a push-back in Athens,” Piccoli wrote in a recent note to clients. “The path to approval will be even less smooth than previously anticipated.”

To put that path into perspective, the research firm has drawn up a decision tree, putting forward its best guesses at the probabilities on all the potential twists and turns in the negotiations between Athens and its lenders (click here for a PDF):

As Piccoli readily admits, this “simplified visualization tool” is anything but simple—capturing all of the possible permutations in Greece’s negotiations would be a hugely complex undertaking.

Greece faces a particularly daunting schedule of debt repayments in June and July, to say nothing of simply keeping up with regular salary and pension payments. One of the few certainties in this long-running drama is that Athens won’t be able to cope without outside help, or some form of debt restructuring, for much longer.

But the patience of Greece’s partners is wearing thin, and as finance minister Varoufakis—who spent his career before government studying game theory—can attest, when it comes to high-stakes negotiations in real life, it’s hard to put what makes sense on paper into practice.