The members tab of the New York state assembly website has the feel of a ’90s high-school yearbook. Each representative gets a spot. Pictures, titles, email addresses; all that is missing is a cheesy inspirational quote. The assemblymen stare back at the reader from the screen, with smiling faces and tailored suits. What one might also notice—or maybe expect—is that they are mainly white. How many? 111 out of 149 seats.

Over the past few months, racial issues have taken center stage in US national media. From Ferguson to Baltimore, apparent instances of discrimination and racial profiling against African Americans have prompted protests and debates across the country. In New York, a series of demonstrations against police brutality followed the killing of Eric Garner last July. A black man from Staten Island, Garner died after a white police officer, Daniel Pantaleo, placed him in chokehold. A Staten Island grand jury decided not to indict the cop.

At the end of April, protesters took to the street demanding justice for another black man, Freddie Gray, who also died in police custody. Racial discrimination is back in the news. As anger and frustration run high in the city, members of the African American community continue to feel misunderstood and misrepresented.

Attempting a racial breakdown in the New York state assembly

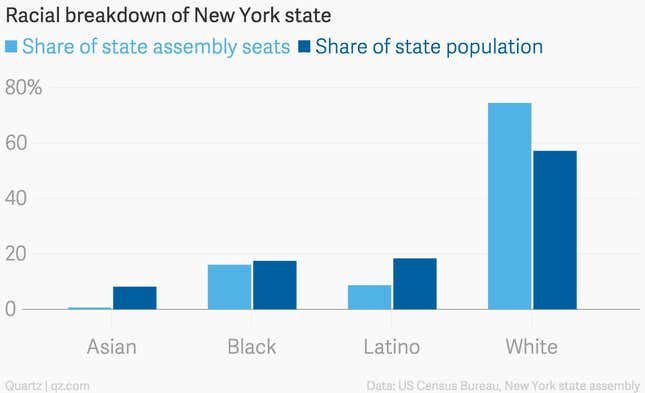

Under these circumstances, it might be surprising to hear that the black community, proportionally speaking, is the most accurately represented group in the New York state assembly among the state’s largest racial and ethnic groups: whites, blacks, Latinos, and Asians. A close look at the distribution of the population along ethnic and racial lines reveals how the African American community is the only case in which the number of black representatives closely mirrors the percentage of the electorate belonging to their racial group (16.11% of seats in the assembly per 17.5% of the population).

Things are worse for Latinos and Asians, who are significantly underrepresented. Asians—who represent 8.2% of the whole population—get one single seat (0.67%) in the current legislature, while only 13 representatives (8.72%) come from a Latino background—18.4% of New York’s population. White assemblymen make up the lion’s share, with 74.5% of seats—even though only 57.2% percent of the population identifies as white.

How do we explain such representational disparities? According to Sayu Bhojwani, president of the New American Leaders Project (NALP), political participation is a “hard-won right” for African Americans, in light of the challenges they have faced historically in their fight for inclusion and recognition. The role of churches and civic organizations as unifying forces is also important, Bhojwani argues. Among such organizations is the New York Urban League, which has been working since 1919 to ensure equal and fair opportunities for the African American population in New York state. According to their president, Arva Rice, higher levels of political participation can be partly considered a result of the black community’s longer stay in the country.

Conversely, the arrival of immigrant communities of Asians and Latinos is a relatively recent phenomenon, which can explain lower levels of involvement in the political and social life of the country. These “newer” minority groups might have fewer role models to follow, be afraid of discrimination during campaigns due to their immigrant status and not be able to raise funds, Bhojwani explains. In her opinion, the experience of authoritarianism in Asia and Latin America might also explain lower levels of political participation among both groups. “Not everybody who is coming here is coming from a democracy,” she says.

Ellen Young, the first Asian American female representative in the New York state assembly (elected in 2006, she was in office until 2008), agrees. She believes that history might help illuminate the reasons behind low levels of political participation among Chinese Americans. The legacy of family executions (a form of punishment for political crimes, such as treason), in particular, might explain their reluctance to participate in the civil process. The family would always want their children not to get involved in politics, she says. “You don’t see Chinese take somebody to court a lot, because good people don’t go to court, neither as defendant nor as plaintiff.”

The limits of data

The challenges when talking about race are many. Throw politics in the mix, and the task becomes even more daunting. One of the obvious limits to this kind of research is the lack of a clear notion of race. The United States Census Bureau, for example, classifies whites, blacks, and Asians as belonging to a race, while it describes Latinos as a group that can belong to any race. But when we look at the overall population of the state of New York, we notice that the majority of Latinos identify exclusively as such. Latinos might not technically be a race, but the “exclusivist” nature of the group makes them comparable to one for the purposes of this study.

Even more comprehensive projects seem to have taken a similar approach. NALP, for example, released Representation 2020, a 2014 report tracking the number of people in office in state governments. Their work is primarily aimed at showing the importance of ensuring the political representation of specific ethnic and racial groups across the country, with a specific focus on the Asian and Latino immigrant communities.

While NALP works on a much larger scale, analyzing the racial makeup of the New York state assembly presents similar challenges. In collecting data, they followed an approach similar to mine, assessing the pictures of each subject available online, the origin of their names and the material provided by the government. “The potential for error is very significant,” Bojwhani says. In particular, some people might identify with more than one race, while women married to men of a different race might take their husbands’ name and complicate the process.

NALP employs an extensive amount of resources to ensure a thorough verification of the information. While my analysis cannot rely on similar support and the method is still susceptible to error, it can at least provide a general idea of how serious under-representation is for certain groups.

The limits of political representation

After the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, many pointed at the gap between the black population and their overwhelmingly white elected officials as a symptom of the country’s problem with race. “Ferguson has been pegged as an outlier but, though the representation gap in Ferguson is particularly pronounced, its basic story of African American underrepresentation plays out in many communities across the country,” a study by public policy organization Demos states.

Ensuring that ethnic and racial communities are fairly represented in government remains the priority for many civic engagement groups. To them, increasing the number of representatives belonging to minorities is essential to building a government that takes their communities’ needs and interests into account. “You want people to come from your background, tradition and culture, who can better articulate your concerns,” Sam Massol, the executive director of nonprofit organization Bridgeroots, says.

But political representation alone might not be sufficient to guarantee the end of inequality. “I don’t think it’s about numbers. I think it’s about power,” Rice says. “If you have a certain number of people in the legislature, how many of them are on the budget committee?” As long as assemblymen are not able to translate their presence in the assembly into effective policy, she argues, the system will remain fundamentally unfair. Political representation might be a good place to start, but is not enough.