In 2013, the composition “A Song of Our Warming Planet” transformed 133 years of global temperature measurements into a haunting melody for the cello. Following its release, “A Song of Our Warming Planet” was featured by The New York Times, Slate, the Weather Channel, National Public Radio, io9, The Huffington Post and many others on its way to becoming a viral sensation and reaching audiences around the globe.

Now the co-creators, University of Minnesota undergraduate Daniel Crawford and geography professor Scott St. George, are back with a new composition that uses music to highlight the places where climate is changing most rapidly.

(Support for this video was provided by the University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment and the College of Liberal Arts. Video production by Mighteor.)

Based on surface temperature analysis from NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, the composition “Planetary Bands, Warming World” uses music to create a visceral encounter with more than a century’s worth of weather data collected across the northern half of the planet. (The specific dataset used as the foundation of the composition was the Combined Land-Surface Air and Sea-Surface Water Temperature Anomalies Zonal annual means.)

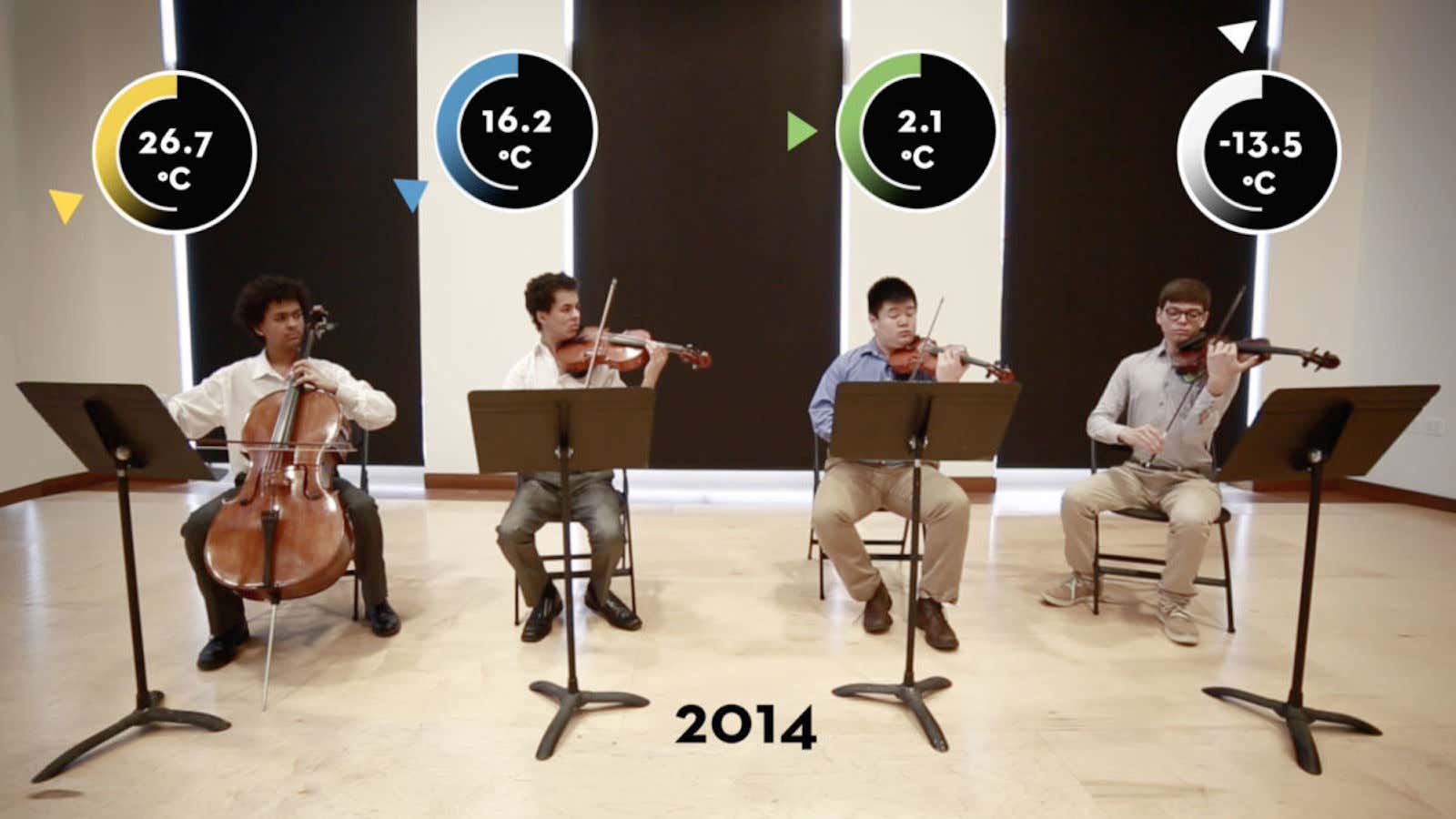

Crawford composed the piece featuring performance by students Julian Maddox, Jason Shu, Alastair Witherspoon and Nygel Witherspoon from the University of Minnesota’s School of Music.

As Crawford explains in the video, “Each instrument represents a specific part of the Northern Hemisphere. The cello matches the temperature of the equatorial zone. The viola tracks the mid latitudes. The two violins separately follow temperatures in the high latitudes and in the arctic.” The pitch of each note is tuned to the average annual temperature in each region, so low notes represent cold years and high notes represent warm years.

Crawford and St. George decided to focus on northern latitudes to highlight the exceptional rate of change in the Arctic. St. George says the duo plans to write music representing the southern half of the planet, too, but haven’t done so yet.

Through music, the composition bridges the divide between logic and emotion, St. George says. “We often think of the sciences and the arts as completely separate—almost like opposites, but using music to share these data is just as scientifically valid as plotting lines on a graph,” he says. “Listening to the violin climb almost the entire range of the instrument is incredibly effective at illustrating the magnitude of change—particularly in the Arctic which has warmed more than any other part of the planet.”